Tithe an Oireachtais

An Comhchoiste um Dhlí agus Ceart, Comhionannas, Cosaint & Cearta na mBan

An Tuarascáil Deiridh

ar Thuarascáil an Coimisiúin Fiosrúcháin Neamhspléach faoi Dhúnmharú Seamus Ludlow

Márta 2006

Houses of the Oireachtas

Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence &

Women’s Rights

Final Report

on the

Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Murder of Seamus Ludlow

March 2006

Contents

Chairman’s Preface Members of the Sub-Committee

Chapter

- Introduction & Victims’ Voices

- Apologies & Acceptance of failings by the State

- The Path to Barron

-The Barron Report

-The Powers of the Sub-Committee

-The context of Events under Investigation

- Co-operation

- The Garda Investigation

-Introduction

-The Initial Inquiry in 1976

-The 1953 Directive

-The 1979 Inquiry

-The conflicting submissions in respect of the stopping of the Garda Investigation

-Submissions from other persons

-Other precedents & the Livingstone Incident

-Submissions from representatives on the Conflict of Evidence

-Resolving the Conflict

- Missing Documents & Missing Evidence

-The Exhibits

-Garda Files

-Department of Justice Files

-RUC/PSNI Files

-Northern Ireland Office Files

-General Observations

-The Letter dated 27 April 1976

- Garda Interaction with the Ludlow-Sharkey Family

- Collusion

- The Inquest

- The Types of Inquiry Available

-A Criminal Prosecution

-Submissions in Respect of the Form of Inquiry

-The Sub-Committee’s Recommendation in Respect of the Form of Inquiry

- Executive Summary & Recommendations

- The Treatment of the Family by the State

- The Conduct of the Investigation by the Gardai

- Re-opening the Investigation

- Missing Documents

- Lack of Co-operation from the British Authorities

- Collusion

- Coroner’s Inquests

- Appendices

- Garda Siochana letter: cross-jurisdictional interviewing of suspects

- Oral Submissions Received by the Sub-Committee

- Written Submissions Received by the Sub-Committee

- Correspondence Received by the Sub-Committee

- Joint Committee Advertisement for Submissions

- Motions of the Dáil and Seanad

- Orders of Reference and Powers of the Joint Committee

- Orders of Reference of the Sub-Committee on the Barron Report on the Murder of Seamus Ludlow

Chairman’s Preface

At the outset, the Sub-Committee wishes to commence this Report by expressing again its deepest sympathy with the relatives of Mr Seamus Ludlow who was brutally murdered on 2 May, 1976. The Sub-Committee was particularly touched by the intense trauma and feelings of abandonment experienced by the relatives. In particular, credit is due to the Ludlow-Sharkey family for their continued search for justice over 30 years.

We have heard submissions made by relatives of Mr Ludlow, serving and former members of the Gardai, office holders, officials and interest groups. We would like to thank all those persons who appeared before the Sub-Committee, who gave of their time so generously. We hope that the process of holding these hearings as part of the consideration of the Report by the Independent Commission of Inquiry goes some way towards assisting the relatives in dealing with their ongoing grief and suffering.

The Sub-Committee believes it is important that the Oireachtas can and does inquire into matters of great public concern. I am grateful to other members of the Sub-Committee for their hard work and commitment to the public interest in carrying out this process.

The Committee is indebted to Hugh Mohan S.C. and Paul Anthony McDermott B.L. for their pro-active role in advising and assisting the Committee. Credit is also due to Ray Treacy and the staff of the Committee who have spent long hours on the organisation and secretarial backup to whom we are very grateful.

The Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights hereby adopts as a report of the Joint Committee, the Report of the Sub-Committee on the Barron Report in accordance with the resolutions of Dáil Éireann and of Seanad Éireann dated 3rd November 2005.

In adopting the report of the Sub-Committee, the Joint Committee wishes to emphasise that all views expressed by the Sub-Committee in the report and all conclusions drawn and recommendations made therein are those of the Joint Committee.

We commend this report to the Houses of the Oireachtas.

Signed

Mr. Seán Ardagh T.D., Chairman of the Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights, 29th March 2006.

Sub-Committee on the Barron Report on the Murder of Seamus Ludlow

Chapter 1

Introduction & Victims’ Voices

- By motions of referral by Dáil Éireann and Seanad Éireann dated 3 November, 2005, both Houses of the Oireachtas requested the Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights or a Sub-Committee thereof to consider, including in public session, the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry on the murder of Seamus Ludlow and the observations made thereon by former Commissioner Wren and Mr. Justice Barron. This is the third set of hearings on Inquiries made by Mr. Justice Barron.

- The Sub-Committee on the Barron Report was asked to consider the report in public session in order that the Joint Committee could report back to Dáil Éireann and Seanad Éireann by 31 March 2006 for the purposes of making such recommendations as the Committee considers appropriate and any changes to legislative provisions and the legislative and other changes, if any, required in regard to the notification to the next of kin of inquests in regard to murders or deaths in suspicious circumstances. This report has been issued accordingly.

Victims’ Voices

- The examination of the Report of the Independent Commission (hereinafter referred to as the Barron Report) commenced with oral submissions from the Ludlow-Sharkey family. The Sub-Committee wished to hear from the family members at the outset of its hearings in order to place them at the centre of its work. It also considered that hearing from these relatives would focus attention on the grief and distress which they still endure.

- Seamus Ludlow was a 47 year old, unmarried forestry worker from Thistle Cross, Dundalk, County Louth. He was killed in the early hours of the morning on 2 May 1976. He was shot a number of times. To date, no-one has been charged with his death. In respect of the cause of the murder the Barron Report concluded that:

“As to the cause of the murder: it would seem to have been a random, sectarian killing of a blameless catholic civilian by loyalist extremists. There is absolutely no evidence to suggest Seamus Ludlow was known to his attackers, or that he had any republican connections or sympathies which might have led to his being targeted by loyalist subversives.”

- Seamus Ludlow was a quiet unassuming man whose life revolved around family and home. He occasionally visited pubs in Dundalk and he was known for his charitable work. There was nothing whatsoever to connect him with any subversive organisation and members of his family recalled that he was firmly opposed to the IRA and similar groups.

- Everyone who described Seamus did so in warm terms. His sister Ms. Nan Sharkey stated:

“Seamus lived with me, or I lived with him. He was a very good fellow. He was a very good living chap. He never got into any trouble and he was good to his parents. Anywhere he went, he would tell me who got a lift from or who he got home with. He never gave any trouble to anyone…He was very kind to my children. He was a good living man too so there is no one to say anything about him.”

Ms. Briege Doyle, a niece of Seamus, who was 16 years old at the time of his death, movingly described her affection for her uncle:

“We loved him. I loved all my uncles but because we were reared with him he was like another father to us. Although there were ten of us he never scolded us. He was a lovely person. I was only 16 and could not understand who would shoot my uncle.”

- In its written submission to the Sub-Committee, British Irish Rights Watch, made the important observation that:

“No-one in authority has ever given the family of Seamus Ludlow the credit that they are due for having themselves pursued the failure of the police investigation. Had they not done so, there would have been no Barron Report and no hearings by the Sub-Committee.”

The Sub-Committee hopes that the following remarks will go some way towards remedying this omission. The fact that we are writing about what happened to Seamus in this report is due to the exhaustive efforts made by his family to ensure that his case has not simply been forgotten. After listening to their submissions, it is clear to the Sub-Committee that the family are still deeply affected by the desperate shock and trauma of the brutal death of Seamus and the continuing pain caused by the subsequent failure on the part of the authorities to bring his killers to justice. The Sub-Committee recognises and wishes to put it formally on record that the Ludlow-Sharkey family have remained steadfast and courageous in their pursuit of justice for Seamus over the past 30 years.

- Mr. Kevin Ludlow, a brother of Seamus, told the Sub-Committee of his upset at the way in which the Gardaí handled the investigation into Seamus’s death:

“We lost a brother and it is a shame to think of how the Gardai treated the family. We were treated very badly for 20 years, until we started this process ten years ago. We got nothing but lies from the Gardai, who blamed the IRA or members of the family for what happened. How they carried on was absolutely wrong. When I saw the body in the ditch and identified it, I just could not believe it. To think that our brother was murdered and we were told lies day after day. Every time we talked to the Gardai we got lies, lies, lies.”

Kevin described how he had identified the body of Seamus at the scene where he was found.

- Ms. Nan Sharkey, a sister of Seamus, explained how the family could not bring themselves to tell their mother what had happened to Seamus:

“We had to tell her he was in a car accident. We could not tell her the way he was shot. She died not knowing. She never knew about it. You could not tell her; she was confined to bed. She was heartbroken.”

- Ms. Eileen Fox, a sister of Seamus Ludlow, was critical of the way in which the Gardaí handled the investigation and the suggestion by them that he had been killed by the IRA:

“We were subjected to an awful lot of harassment from Gardaí who were in and out every day. For weeks they were with me in the house every day. They were saying it was the IRA and this and that.”

- Mr. Michael Donegan, a nephew of Seamus, explained that his father, Kevin Donegan (who had been in the Irish Defence Forces for 14 years and who was of the view that if he heard it from the Gardai it must be true), had believed the suggestion by the Gardaí that the killing of his brother was arranged by the IRA and carried out by members of the Ludlow-Sharkey family because Seamus was an IRA informer. He described the tension this gave rise to among the family members:

“There is no question about it; the killing traumatised the family, turned us upside down. To a large extent it put our lives on hold for the next 30 years, which is why we are here today…He met these gardai over a number of months and they just kept putting it home to him: the IRA, the IRA, the IRA. He went to his grave with that belief: that it was the IRA, because of what they told him. There is no question that it caused a lot of conflict in my house. I am not going to try and avoid it now.”

- Mr. Brendan Ludlow, a nephew of Seamus, described how his parents had put two Gardaí up in their house between 1972 and 1976. He also pointed out that he had been a member of the Defence Forces operating on the border where his uncle was killed from 1977-1999. He explained:

“This is how we treated the State. The State has treated us as described from 1976 to date; we have had nothing else but the same treatment from the Garda Síochána”.

When Deputy Power asked him if he felt that the Garda investigation at the time had been carried out properly he said that in his opinion it had not been and added:

“I think they did not want to know about the Ludlow family. The statement was made that it was political and that he was shot by his own”.

- Seamus’s niece, Ms. Briege Doyle, described her affection for her uncle and how he was like a father to her. She described how she was the fourth oldest in the family and was 16 at the time of the murder. She stated that:

“I am Mrs Sharkey’s daughter, I was reared in the same house as Seamus. I was only 16 when he was murdered. When you are 16, it was an awful thing for your uncle to die and it was worse that he was shot. I remember the special branch questioned me in a car on my own. I was taken into a car outside auntie Eileen’s house and I was asked who did I think killed my uncle. I was only 16, I had not a clue. I did not know anything about the troubles in the North. He was a quiet man. I was reared with him - so was Jimmy - and he would not harm a hair on your head. It is sad to see a young man die like that. He did not deserve what he got.”

- Mr. Jimmy Sharkey, a nephew of Seamus, told the Sub-Committee:

“In general, the Garda Síochána’s behaviour towards us over 30 years has been nothing short of terrible. It has been a terrible experience for us all and even harder for Kevin Ludlow, Eileen Fox and Nan Sharkey. It is also hard for the rest of us at times. I was not surprised that the Gardai did that or that the State acted as it did. They have done so in similar cases, including the Monaghan and Dublin cases and, as we will see, that of Dundalk. They simply did not care. The only way that one will ever get answers is through an independent inquiry - it must be an inquiry.”

Deputy Hoctor asked Mr Sharkey about the mysterious fact that an anniversary mass is celebrated every year for Seamus in Staffordshire in England and he indicated that the family have no idea who requests this mass.

- The Sub-Committee heard during its hearings from the Secretary General of the Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform and noted that he stated that assistance might be provided to the family by the Criminal Injuries Tribunal and the Remembrance Commission.

- The Sub-Committee wishes to thank the family for the contribution that they made and to record the fact that they provided full and open co-operation with our work.

BIOGRAPHICAL DETAILS OF THE LUDLOW-SHARKEY FAMILY

- The details of the family members are:

Mr. Kevin Ludlow, brother of Seamus Ludlow.

Ms. Nan Sharkey is a sister of Seamus Ludlow who lived with him at the time of his death.

Ms. Eileen Fox, a sister of Seamus Ludlow.

Mr. Michael Donegan, a nephew of Seamus Ludlow.

Ms. Briege Doyle, a niece of Seamus Ludlow, who was 16 years old at the time of his death.

Mr. Brendan Ludlow, nephew of Seamus Ludlow.

Mr. Jimmy Sharkey, a nephew of Seamus Ludlow.

Chapter 2

APOLOGIES AND ACCEPTANCE OF FAILINGS BY THE STATE

- During the course of the hearings certain apologies and acceptances of failings were made to the Ludlow-Sharkey family on behalf of the State. It seems appropriate to the Sub-Committee to record them all together in a single place in this report.

- The current Garda Commissioner, Noel Conroy noted the failure to follow up the information provided by the RUC in 1979 and stated that “Thereafter the trail went dead. Unfortunately we are in a situation today where we have not resolved that crime. From a Gardai point of view, I regret this very much in so far as I can see it, it was a failure on the part of the Garda Síochána not to have had the crime thoroughly investigated and brought to a satisfactory conclusion.”

- In answer to a question from Deputy Hoctor as to whether he was willing to apologise on behalf of the Garda Síochána for its failure to act as expected, Commissioner Conroy stated:

“I have no difficulty apologising to the family on two fronts: regarding the overall investigation, in so far as we did not bring it to a successful conclusion; and in respect of our handling of the inquest. I apologise to the family in that regard. As I said earlier, I regret the Garda Siochana did not bring this investigation to a satisfactory conclusion. I have no doubt that management within the organisation feels the same.”

- In response to a question from Deputy Costello, Commissioner Conroy expressed regret to the family for the way the inquest into Seamus Ludlow’s death was handled in 1976:

“I am very disappointed at the way in which that episode transpired. It is very regrettable. The family of the late Seamus Ludlow was informed on the morning of the inquest. To make matters worse – from what I have read in the documents – the Gardai did not seek the consent of the coroner to have the inquest adjourned. That is the least I would have expected to be done in order that the family would be able to attend and hear the evidence.”

- Former Commissioner Byrne stated that “I am a great believer that we should say we are wrong if I believe that is the case, rather than waiting for others to say it. Without pointing the finger at anybody, we, as an organisation, failed in terms of following through the next step in this investigation. There is no issue of conspiracy. It was a human failure that there was no follow up.” He agreed with Deputy Ardagh that it was an overall management failure.

- In his presentation to the Sub-Committee, the Minister for Justice, Equality & Law Reform, Mr Micheal McDowell, T.D., stated that:

“On this occasion I express deep regret to the family and next of kin of Mr Seamus Ludlow, on what by any standards was a deeply unsatisfactory and inexcusable experience in the holding of the first coroner’s inquest.”

In respect of the Gardai investigation, the Minister added:

“The Garda investigation into the murder of Seamus Ludlow, undoubtedly, had good and, unfortunately, very bad points. The 1976 investigation, as Judge Barron said, was a professional one but what happened in 1979 cannot be stood over. I do not think any member of the Garda Siochana has since attempted to do so. I cannot do a better job of highlighting these issues than was done by the inquiry. On the basis of the findings of the Barron Report, the Ludlow family undoubtedly, has a sound basis for feeling very aggrieved at a number of events surrounding the murder, including those relating to the interview of suspects and the original coroner’s inquest.”

- Former Detective Sergeant Corrigan expressed how devastated he was when the investigation was not pursued in 1976. Former Detective Inspector Courtney expressed the disappointment he felt when he was told by C3 that the investigation would not proceed and said “It never left my mind, even though at the time I was investigating several murders up and down the country.”

- The Sub-Committee welcomes all of the above comments.

Chapter 3

THE PATH TO BARRON

- Towards the end of 1995, members of the Ludlow-Sharkey family received information from a journalist to the effect that a group of loyalist extremists from mid-Ulster was responsible for Seamus’s murder. Over a series of meetings, the journalist named specific persons whom he believed should have been suspects for the murder. He suggested that the family hold a press conference and also contact the Garda Commissioner with this information.

- On 2 May 1996, the 20th anniversary of Seamus’s death, a press conference was held by the family in Dublin. A letter was also sent to the then Garda Commissioner. The letter expressed concern at the failure to effect a prosecution in the case and at “the general conduct of the investigation by the Gardaí at the time”. In particular, it was said that in the period following the murder, the family had been led to believe, by individual gardaí, that republican paramilitaries were responsible. The letter concluded:

“We would greatly appreciate, therefore, if you as Garda Commissioner, could see your way to order a new investigation into the murder with a view to bringing to justice those responsible for this terrible crime. The Ludlow-Sharkey family pledge its total and full co-operation in any such new investigation and undertake to provide the Gardaí with the name of the person believed to be the killer. We should point out however that we understand the gardaí already possess this information.”

- A new investigation was ordered by the then Commissioner and was conducted by Detective Superintendent Ted Murphy of the Special Investigation Unit, Crime Branch. This reactivation of the case brought to light information received from the RUC in 1979 concerning four loyalist suspects for the killing. When this was brought to the attention of the Commissioner in 1997, contact was made with the RUC and the four men were arrested by RUC officers in February 1998. The four, whose names were not among those given to the Ludlow-Sharkey family by the journalist in 1995-96, were interviewed and then released. During the course of questioning two of the four men admitted being present when Seamus Ludlow was murdered but denied being involved. A file was then sent to the Director of Public Prosecutions in Northern Ireland for a decision on whether charges should be brought against these men. No prosecution was brought on the basis of insufficient evidence.

- A Victims’ Commission was established in the aftermath of the Good Friday Agreement and arising from its recommendations the Barron Inquiry commenced an examination into all aspects of the killing of Seamus Ludlow.

The Barron Report

- In his report Mr. Justice Barron concludes that Seamus Ludlow was murdered by loyalist extremists, seemingly at random:

“The facts and circumstances as they appear to the Inquiry have been set out in this report. They indicate that Seamus Ludlow was picked up by a car near the bridge on the Dundalk to Newry road; that this car was driven by James Fitzsimmons and contained three other passengers – Richard Long, Samuel Carroll and Paul Hosking. Information obtained by the RUC from Hosking suggested it was Carroll who shot Seamus Ludlow. The inquiry has not been in a position to test the veracity of this allegation.”

It is not the function of the Sub-Committee to apportion guilt or innocence to any named individual and thus we express no view on this conclusion.

- Mr. Justice Barron also states that the original investigation of 1976 was conducted competently and diligently by Gardaí and that they are in no way to blame for the failure to identify the killers.

- The key question for the Barron Inquiry was why the information supplied by the RUC in 1979 was not pursued. The Inquiry believed that the only credible explanation for this is that a direction was given to the investigating officer at the time to abandon plans to have the suspects interviewed outside of the jurisdiction. As to why this might have been the case, the Inquiry stated that such a policy may have led to demands for reciprocal arrangements by the RUC. The Inquiry states:

“Such a policy could have arisen out of a combination of one or more of the following factors:

- A risk that republican subversives would target RUC officers coming to this jurisdiction;

- A risk that republican subversives would view such co-operation with the RUC as a justification for attacking members of An Garda Síochána; and

- A fear of the political consequences arising from the fact that a certain sector of the population would perceive any co-operation with the RUC in this State as a ceding of sovereignty to the British Government.”

The Inquiry concluded that:

“The Inquiry believes it most probable that the decision was made by Deputy Commissioner Laurence Wren (C3). Before doing so, it is likely that he would have discussed the matter with other senior Gardai and possibly senior officials from the Department of Justice. However the absence of files means that this cannot be confirmed.”

- In respect of the inquest, Mr. Justice Barron concluded that there appears to have been no justification for the failure to notify Kevin Ludlow of the date of the inquest into his brother’s death. Given the nature and circumstances of the death, other family members should also have been notified. The fact that the inquest proceeded reflects a belief that because the cause of death was undisputed, the inquest procedure was a formality. While this was technically true, the decision to proceed in the absence of family members caused them unnecessary hurt and annoyance at a time of extraordinary sadness and difficulty in their lives.

- Mr Justice Barron attended before the Sub-Committee and explained that he dealt with this Inquiry and prepared his Report in the same way as he dealt with the other matters on which he reported. Essentially, the information came from the Gardaí and he had to analyse that and see where that would bring him. He spoke to the family on a number of occasions and he sought information from the then RUC but, apart from some very limited information it supplied regarding the 1977 to 1979 period, that was as much as he got. He was satisfied that he had received full co-operation from the Gardaí and from the Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform. He felt that people had been willing to tell him what they knew but importantly he stated that it was obvious that he was not given the full picture by one or more people. In response to a question from Senator Walsh as to whether the absence of powers of compellability and the giving of sworn evidence represented a serious shortcoming in his Inquiry, Mr. Justice Barron responded by saying:

“I do not think so. The people we spoke to seemed willing to tell us what they knew. It is obvious we were not given the full picture by one or more people but, generally speaking, we were given the full picture.”

The Sub-Committee is of the view that this comment must be viewed in light of the fact that Mr Justice Barron had no powers either to compel persons to attend or to compel documents to be produced. This absence of powers is of obvious significance in the light of Mr Justice Barron’s view that he was not given “the full picture by one or more people”.

- The Sub-Committee wishes to express its gratitude to Mr. Justice Barron for the work he and his staff have done in producing the report and for the assistance they gave us in the course of our hearings.

The Powers of the Sub-Committee

- At the outset it should be noted that the Sub-Committee is bound by very precise terms of reference beyond which it cannot stray. In particular, the Sub-Committee is not conducting an investigation of its own into the events that happened during the period concerned, nor is it seeking to apportion guilt or innocence to any individual person or body. It has neither the jurisdiction nor the legal authority to perform any such function. In Maguire v Ardagh [2002], the Supreme Court granted a declaration that:

“… the conducting by the Joint Oireachtas Sub-Committee of an inquiry into the fatal shooting at Abbeylara on the 20th April 2000, capable of leading to adverse findings of fact and conclusions (including a finding of unlawful killing) as to the personal culpability of an individual not a member of the Oireachtas, so as to impugn his or her good name is ultra vires in that the holding of such an inquiry is not within the inherent powers of the Houses of the Oireachtas.”

Everybody who appeared before us was asked to respect the fact that we cannot stray beyond our terms of reference or our legal powers. The Sub-Committee is grateful to everyone for their co-operation in this regard.

- It should also be noted that the Sub-Committee has no powers of compellability and thus everyone who came before it did so voluntarily and we thank them all most sincerely for their attendance on that basis.

- A couple of crucial witnesses refused to attend. The Sub-Committee expresses its regret that these persons felt unable to assist it with its inquiry.

- Former Detective Sergeant Daniel Boyle wrote to the Sub-Committee and stated that:

“In confirmation of my telephone conversation to you, also on this date, I wish to say that I will not be attending the hearings on 14thFebruary 2006.”

Subsequent attempts to ask former Detective Sergeant Daniel Boyle to attend were unsuccessful. As will be seen below, former Detective Sergeant Daniel Boyle is a crucial link in the central conflict of fact that emerged in both the Barron Report and the testimony before the Sub-Committee. It is therefore a matter of particular regret to the Sub-Committee that he felt unable to attend.

- Mr Jim Kirby, former Assistant Principal in the Department of Justice, wrote to the Sub-Committee and stated:

“As I explained to you then and as I have already told Judge Barron that I have no recollection of the murder of Mr Ludlow or of any subsequent developments in relation to that murder.

I am satisfied that I have no information available to me that would be of assistance to the Sub-Committee in fulfilling its remit.”

We regret he could not attend, as given the frequency of contact between the Department of Justice and the Gardaí, his assistance would have been helpful to us in understanding the events that occurred.

- Through the good offices of the PSNI the Sub-Committee forwarded correspondence to the four persons named by the RUC as the suspects for the murder but no response was received from them. In respect of one of the suspects, the PSNI were unable to forward the correspondence due to security concerns.

The Context of Events under Investigation

- In considering the matters which are the subject of this report, it is clearly important that they should be viewed in the context of the times. The period 1976-1980 was clearly very difficult and fraught with tension. The British Government were pressing for greater co-operation on three security-related matters: “hot pursuit” across the border, permission for RUC officers to question suspects in the State, and overflights by British military aircraft. These three issues evoked strong reactions amongst ordinary people in the State, and such popular opposition was inevitably reflected in the policies and attitudes of the Gardaí and successive governments.

- A number of persons who appeared before the Sub-Committee referred to the nature of the times when the events under consideration arose. Minister McDowell stated that:

“We are examining the events of 30 years ago through the prism of all that has occurred since, including North-South co-operation and political progress. Given that a high level of co-operation between the Garda and the Police Service of Northern Ireland is now the norm, as evidenced by their co-operation in the investigations into the Northern Bank raid and other organised crime, it is hard to appreciate how different things were - regrettably - in the 1970s. It may be trite to say they were different times, but that is the reality. Our attitudes to Northern Ireland and what constituted appropriate contact between the respective forces of law and order in the two jurisdictions were informed by different considerations of history. I cannot put it more forcefully than this. The Sub-Committee should bear in mind that the issue of extradition, for example, was considered extensively in 1973-74 under the Sunningdale Agreement. A bilateral commission was established when no agreement was reached in this fundamental area of law enforcement. The Criminal Law (Jurisdiction) Act 1976 which was passed as a result of the commission’s activities did not provide for extradition but for mutual jurisdiction on either side of the Border for serious offences, including murder. When one considers the current circumstances, it is clear that relations between the two sovereign states on this island were very different in the 1970s.”

- In his written submission to the Sub-Committee, Commissioner Conroy stated that “The period 1976 to 1980 was one of huge turmoil. Deep divisions of distrust existed, not only between the nationalist and unionist communities in Northern Ireland, but also between Governments of the United Kingdom and this State.”

- Former Chief Superintendent Cotterell stated that:

“The 1970s was a deadly time on the Border. It was terribly busy because all sorts of things were happening. There were many incursions, particularly air incursions. All these events had to be investigated and a file sent to headquarters for the Department of Foreign Affairs, which then made the appropriate protests.”

- It is difficult for us to appreciate this kind of turbulence at this remove of time. The Sub-Committee recognises that the turbulence of the times may go some way to explaining what occurred. However it does not believe that this turbulence excuses the fact that an investigation into the murder of one of the State’s citizens stopped despite the fact that four suspects had been identified. No matter how turbulent the times, the investigation into the murder of a citizen of the State should not be sacrificed for any reason.

Chapter 4

CO-OPERATION

- In previous reports the Sub-Committee has expressed its concern about the lack of co-operation provided by the United Kingdom authorities. Regrettably, it received no co-operation in respect of these hearings either. By letter dated 16 January 2006, the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, the Rt Hon Peter Hain MP, stated that the British Government had provided Mr Justice Barron with information that he requested on a number of issues relevant to his report and added:

“All relevant information held by the British Government has therefore already been passed to Justice Barron and incorporated into his report.

While I support the important work being done by Justice Barron’s Independent Commission of Inquiry and by the Sub-Committee, I do not believe that there is anything that I could usefully contribute to that work at the public hearing.”

In fact when one turns to the Barron Report one discovers that an absolute bare minimum of information was received from the authorities in Northern Ireland.

- In the course of the hearings, Deputy Ardagh summarised the views of the Sub-Committee in respect of this problem, particularly in the context of the kidnapping of Mr Donegan by the British Army:

“I am very disappointed that we have still not been able to receive from the Northern Ireland authorities any information of any description regarding Mr Donegan’s interviewing, particularly considering that helicopter travel was involved. One would assume that there would be information regarding trips for helicopters. Even that information has been withheld and has not been forthcoming. I state our utter disappointment with the authorities in Northern Ireland for their non-cooperation with us.”

- A slightly more helpful response was received from Sir Hugh Orde, the Chief Constable of Northern Ireland. He stated that because the role of the RUC in the case had been well documented and as he had no personal knowledge of the case, he did not consider he would be able to add anything of value by attending the Sub-Committee’s hearings in person. However he drew the Sub-Committee’s attention to the work of the Historical Enquiries Team (the HET) which has a remit to review and re-investigate where possible all deaths in Northern Ireland attributable to “The Troubles”. He informed us that:

“Whilst the unit will not examine deaths or incidents in the Republic, there is no doubt that many of the organisations and individuals were involved in criminal acts on both sides of the border and will be of interest to both jurisdictions. The HET have had an initial meeting with An Garda Siochana to discuss liaison.

The whole process will be underpinned by a developing Analytical database, which will contain all the details relevant to each case and which can be used to identify both links between cases (intelligence or forensic/ballistic), gaps in intelligence or trends/evidential possibilities.

There is potential for a liaison facility between the HET and An Garda Síochána to monitor progress in the continuing review process, utilizing the Analytical database, to highlight any relevant links to the Ludlow case or further evidence uncovered and to conduct any further joint enquiries that may be appropriate.”

- The Sub-Committee wishes to once again record its disappointment at the lack of co-operation from the British authorities.

Chapter 5

THE GARDA INVESTIGATION

Introduction

- One of the issues that has arisen on foot of the Barron Inquiry is whether there was a policy that dictated that Gardaí would not interview suspects North of the border during the time in question. As with the Barron Inquiry, the Sub-Committee heard sharply conflicting submissions in respect of this issue. It is surprising that what would appear on its face to be a straightforward question of fact has produced such a dichotomy of evidence. Whilst the Sub-Committee does not have the power to adjudicate on which view is correct, it can and must identify precisely how the conflict of evidence arises.

The initial inquiry in 1976

- It will be recalled that Mr. Justice Barron concluded that the original investigation of 1976 was conducted competently and diligently by Gardaí and that they are in no way to blame for the failure to identify the killers.

- When questioned by Deputy Hoctor, former Detective Sergeant Corrigan said that the investigation did not close down after 21 days but that the emphasis on it might have closed in terms of the heavy concentration of personnel on it. He said that in murder investigations a period of a month or two for the initial investigation is quite commonplace because personnel from headquarters and investigators are taken away to deal with other crimes.

- It became evident to the Sub-Committee that the family do not agree with this. Deputy Costello asked Mr Jimmy Sharkey if he agreed with that analysis and he replied in the following terms:

“No. The failings lie in 1976. If the committee members look three years further on to 1979, then they are missing the whole thing. They are not seeing the wood for the trees. In 1976, the Gardai probably did not know who killed Seamus Ludlow as they did not have enough concrete information, suspects and so on, but they knew the IRA did not do it. There were only two groups carrying out killings at that time - apart from the SAS, which came on the scene around that time - and they were the republicans and the loyalists. The Gardai would have known that the loyalists were involved in the bombings in the town in December 1975, six months before Mr. Ludlow was killed. They had to be channelling their intelligence elsewhere, but they kept a spin on the incident the whole time that it was the IRA, for the reasons that I outlined earlier.”

- In contrast, in his written submission to the Sub-Committee, Commissioner Conroy stated that:

“From an examination of the papers into the original Garda investigation in 1976 I am satisfied that a thorough investigation took place at that time and that all of the usual practices employed by An Garda Siochana were put in place during this inquiry. The conclusions of Mr Justice Barron endorse this view at page 83 of his Report, where he states ‘the evidence shows that it was carried out competently and diligently by the Garda Officers concerned. The failure to identify the killers at that time was due entirely to a lack of reliable intelligence information – for which Gardai were in no way to blame’.”

- The Sub-Committee cannot adjudicate on this issue. However, a number of serious questions did arise.

- Why was the Gardai investigation in 1976 stopped after such a short period of time?

- Is it possible that the Gardaí had a disposition towards believing that the attack was conducted by the IRA and did not sufficiently investigate other possibilities?

- Why was there no attempt or real attempt to seek co-operation from the authorities in Northern Ireland?

- The failure to seek co-operation from Northern Ireland is even more surprising given the fact that by letter dated 27 April 1976, the RUC had identified seven suspects worthy of note, including a person, who was one of the four persons ultimately named as a suspect in the killing of Seamus Ludlow (see para 132-135).

The 1953 Directive

- Before moving on to consider the 1979 Inquiry, the text of a directive from the Assistant Commissioner “C” Branch dated 13 November 1953, needs to be set out as it plays an important role in the conflict of testimony that will emerge. The Directive stated:

“In accordance with established practice, reciprocal arrangements exist whereby members of other police forces may visit the area of the Republic to pursue enquiries into ordinary crimes committed in their area, interview suspects witnesses etc…

In all such cases, the members of the other police force should be accompanied by a member of the gardai of the same rank as visiting officers, who should remain present as far as possible at all interviews with members of the public.

In the case of crimes or offences or enquiries of a political nature arrangements should not be made whereby members of other police forces can interview persons in this country or accompany members of An Garda Siochana making such inquiries. In these cases, any enquiries which are considered necessary to be made should be made by Gardai themselves. The result of any such enquiries made by gardai should not be communicated direct locally to the police forces concerned, but forwarded to the Commissioner (3C section).”

It will be seen from the plain words of the Directive that it deals exclusively with members of other police forces who wish to visit the Republic. On its face it does not say anything about the circumstances in which members of the Gardai could travel North.

The 1979 Inquiry

- In respect of the 1979 investigation, the Barron Report concluded:

“In the final analysis it seems that the reason for the failure to pursue the questioning of the suspects lies in the perception that it was contrary to Government policy to do so. If that was the correct view, then it would have been known to Deputy Commissioner Wren. While it may or may not have been discussed with officials in the Department of Justice, it would have been something of which they were all aware. This would explain why the garda Commissioner Patrick McLoughlin was not told, something which a later Commissioner, Patrick Byrne, accepted in his letter of 10 January 2003.” (page 81)

- Mr. Justice Barron appeared before the Sub-Committee and reiterated the finding in his report that the 1979 inquiry had come to a halt because of policy reasons:

“The report has drawn the conclusion that if there was not a policy, it was certainly a perception of the Garda that there was such a policy”.

- He was also asked by Senator Walsh if he thought that one of the reasons for Gardaí not going up North to interview suspects was due to personal safety concerns and responded:

“I mentioned this as a possibility and I was told it was not correct. I cannot put it any firmer than that. At this remove, it would be unlikely for anybody to admit that was a cause. From what I saw of individual gardaí, I do not believe it would have been a cause.”

- It emerged during Mr. Justice Barron’s submissions to the Sub-Committee and questions put to him in respect of the evidence of former Detective Inspector Courtney, former Assistant Commissioner Ainsworth and former Commissioner Wren that there is significant conflict between the findings made in the report and the submissions of former Commissioner Wren.

The conflicting submissions in respect of the stopping of the Garda investigation

- In his report, Judge Barron noted that former Detective Inspector Courtney said that he discussed the case with former Detective Sergeant Daniel Boyle who he says told him former Commissioner Wren had said that, if the four suspects were to be extradited to the Republic, a similar number of IRA extraditions would be sought by the RUC and he did not want this to happen.

- Former Detective Inspector Courtney was the border Superintendent at the relevant time and stated that in his view what Mr Justice Barron said in his report was accurate. In respect of 1976 he stated:

“We had an open mind on the investigation. We investigated it from all angles, keeping in mind that it could have been an ordinary domestic murder, a Provisional IRA or UDA murder. We had no definite suspects or line of inquiry.”

- Former Detective Inspector Courtney described how he had been surprised and delighted when the RUC had given him the names of the four suspects. He said that the purpose of his visit North on that occasion was in relation to the Dundalk bombing. The RUC had told him that they had received the information they were giving him approximately 18 months previously. Because of the detail he was given, he was satisfied that the information was reliable. He was of the view that the four named suspects should be interviewed and investigated. In respect of the information, he stated that “I sent it on to C3 whose duty it was to make arrangements to have the people interviewed. My function was just to report the matter, to pass on the information.” He said that he would have had no authority to go North to interview suspects and that it was the duty of C3 to make such arrangements. He said his link persons in C3 were late Chief Superintendent Michael Fitzgerald and, in his absence, former Detective Sergeant Daniel Boyle. He was clear that one could not go outside of the State in respect of the interviewing of suspects without permission from C3.

- Former Detective Inspector Courtney made it clear that the RUC had been very selective in their co-operation with the Gardaí. As we know, they only passed on the information in respect of the four named suspects 18 months after they had received it themselves. In addition, they did not provide any assistance in respect of the car used in the Dundalk bombing. This shows that at that time the RUC appeared to be drip feeding information to the Gardaí and the question arises as to whether they were only passing on information to serve their own ends.

- Former Detective Inspector Courtney said that he had been surprised when he had spoken to former Detective Sergeant Daniel Boyle and had been told that nothing would be done about the investigation and he described how then the investigation “just fizzled out”. He said that “The reason given was that if the four suspects were extradited, the RUC would be looking for four IRA suspects to be extradited to Belfast.” He was 100 per cent certain that that was what former Detective Sergeant Daniel Boyle had said to him. Former Detective Inspector Courtney went on to say that all he himself could do was to report the facts and take directions. As former Detective Sergeant Daniel Boyle was his link in C3 he would not have been in a position to question his authority. He said that he was satisfied that he had responded to all correspondence from C3 and that the fact that certain letters might not have been located at this stage did not mean that he had not answered the correspondence. The correspondence with C3 would go through Chief Superintendent Dan Murphy. He said that he believed at the time that he could have secured a conviction “One must strike when the iron is hot. We should have interviewed them at the time, not years afterwards, since the trail grows cold as the years pass by.” Deputy Power asked him if he contended that it was former Commissioner Wren who made the decision not to question the suspects and he stated that “I do not know what the position was in this regard. He was probably told to do it. I reported to him and gave him the names of the suspects.” He then said that he assumed it came down from former Commissioner Wren but very fairly added that he could not be certain of this as all he knew was what former Detective Sergeant Daniel Boyle had told him in March or April 1979. Deputy Ardagh asked him if his colleagues had expressed dissatisfaction that the four suspects were not interviewed because of the actions of people at a higher level and he stated that that was the case and that they felt that at least the four suspects should be interviewed. Deputy Ardagh asked him if he could have done anything on foot of his dissatisfaction and he explained that: “At the lower level, you can discuss it all right. I was satisfied with what former Detective Sergeant Daniel Boyle said, which I will always remember because I was so disappointed with the news. It never left my mind, even though at the time I was investigating several murders up and down the country.”

- Former Detective Inspector Courtney also identified an additional concern that the Barron Report gave rise to in his mind:

“Following the receipt of information from the RUC regarding the names of the suspects, I submitted my report through the channels of communication to the Commissioner of C3. I was surprised when I got this book after Christmas to discover that this information had already been received by the Commissioner of C3. That was the first I knew about it. I am disappointed that the Commissioner of C3 had not told me this, given that I had been very much in touch with him at the time, as many subversive murders and other crimes were being committed and there was a great deal of interaction between him and me. I felt I should have been told C3 had that information but I was never told. C3 was responsible for the investigation and making arrangements to have the suspects interviewed and possibly extradited at a later stage. I had nothing to do with this. My position was to report the facts as I got them from the RUC, the names of the suspects, which I did.”

- Former Commissioner Wren was the Deputy Commissioner of C3 in the period January to April 1979. He told the Sub-Committee that he had no recollection of having been approached by former Detective Inspector Courtney for permission to interview the four suspects. He said that any such decision would not have been made by C3 without reference to a higher authority. He complained that:

“Despite the foregoing, which clearly shows that there was not one word to indicate that I was approached about the matter in any way, the Inquiry has come to the conclusion that it believes it more probable that the decision was made by former Commissioner Wren. In light of the foregoing and when former Detective Inspector Courtney’s direct superiors do not appear to have any knowledge of his efforts in this regard, how this conclusion could be reached beggars comprehension. I sent a memo to this effect at the time, to which there was a very brief reply stating that the relationship between the gardaí and the Department of Justice and the general policy in such matters is fully set out in pages 66 to 81 of the report and that the conclusion reached was based upon the information contained in these pages. I could not see it in those pages.”

It should be noted that when he appeared before the Sub-Committee, Mr Justice Barron defended his finding by stating that “The Report was given to C3. It is doubtful such a highly unusual piece of information would not have been given to the head of that division, who was former Commissioner Wren.”

- Former Commissioner Wren said that he wanted to confirm to the Sub-Committee that the issue of allowing former Detective Inspector Courtney to travel to Northern Ireland to interview suspects had not been discussed with him by anybody. He explained that Northern Ireland “… is outside the jurisdiction of An Garda Síochána and that our members have no legal right to operate there. Indeed, any such practice was specifically ruled out in a crime branch Directive issued to the force as far back as 1953. That is the procedure that has been followed since and was brought to the notice of the Inquiry, since it is referred to in the report at the bottom of page 79.” The status and meaning of this Directive was to become an issue giving rise to further conflict in submissions to the Sub-Committee.

- Former Commissioner Wren was emphatic in his recollection that the question of him giving authorisation to go North, simply did not arise:

“There was no way in which I could have authorised former Detective Inspector Courtney or any other member of the force to go to the North because we had no jurisdiction or authority, irrespective of whether we had been invited. An invitation from a police officer in Northern Ireland confers no authority or legitimate status on a member of the Garda Síochána questioning suspects in that jurisdiction. A member in this position would have been on his own if anything had gone wrong as there was no law to cover that eventuality.”

- Former Commissioner Wren went as far as to suggest that there was in fact no reason for the Garda investigation to have ceased:

“The investigation did not have to cease because the Garda Síochána could not travel to the North. The normal procedure would have been for the Garda Síochána to request assistance from those who had information in the North and to have the suspects interviewed and dealt with in that jurisdiction, without extradition. The Offences against the Person Act 1861 covered the granting of legitimacy to an investigation in the North into a murder that had taken place in the South. I will not refer in great detail to the legislation but the investigation could have been handled in this fashion. The question of my refusing to allow any member of the force to travel to Northern Ireland does not arise”.

- Former Commissioner Wren also agreed that the 1953 Directive was adopted as policy and would have been known to have been such. When Deputy Ardagh asked him about the status of the Directive he stated that “one could assume that because it was the policy for the whole force. It merely clarified the legal position in case anyone thought they had authority to go North. It merely reminded them that it was not done.”

- In response to questions from Senator Walsh, former Commissioner Wren stated that C3 would not have been the appropriate body from which to seek permission to go across the border to interview suspects. He was clear that C3 had no involvement with Gardaí wishing to travel North and thus it would have been wrong for former Detective Inspector Courtney to have made the request from C3. When questioned by Senator Walsh about who would give permission he stated that “Nobody would give permission to go to the North to question suspects. I am not aware of any occasion on which that happened.” He added that “C3 was not an investigating unit; we were just a conduit for passing on to the Department whatever intelligence or information had been received about one thing or another.” He said that he could not offer the Sub-Committee any reason why the investigation was not pursued. The Sub-Committee in seeking information on this issue has received correspondence from the Garda Commissioner’s Office which does detail occasions on which Gardai did interview suspects in Northern Ireland, both accompanied and unaccompanied (see para 92). In response to a further question by Senator Walsh, former Commissioner Wren said that he was not aware of any RUC officers coming South, at least not officially.

- Thus there is a clear conflict between the position of then Detective Inspector Courtney and that of former Commissioner Wren. Unfortunately, former Detective Sergeant Daniel Boyle declined an invitation to appear before the Sub-Committee. His position has to be gleaned from three lines in the Barron Report:

“D/Sgt Daniel Boyle (now retired) was also questioned by C/Supt Murphy. He said he had ‘a vague recollection’ of the Ludlow case, but had no recollection of any conversations with former Detective Inspector Courtney on the subject.”

Thus, the one person who might be in a position to resolve the conflict with some degree of certainty does not appear to be in a position to do so. The Sub-Committee regrets that it did not have an opportunity to hear for itself from former Detective Sergeant Daniel Boyle as his submissions might have assisted in identifying the nature and parameters of the conflict more clearly. The Sub-Committee also remains unclear about precisely what happened to the proposed trip to Glasgow by Chief Superintendent Murphy to interview one of the suspects.

- Former Detective Sergeant Corrigan accompanied former Detective Inspector Courtney to RUC Headquarters in Belfast in 1979. He indicated that he agreed entirely with the contents of the Barron Report. He said that they had travelled to Belfast in connection with the car used in the bombings in Dundalk. He had regarded the information that the RUC had given them about the four suspects for the murder of Seamus Ludlow as credible. He said that he was grateful to get the information and did not question the delay on the part of the RUC in providing it. In response to a question from Senator Walsh, his recollection was that the RUC had not indicated that any of the four persons they had named were members of the security forces in the North. He pointed out that the RUC provided no information in respect of the car used in the Dundalk bombing. He stated that:

“I was devastated when the case was not pursued. I returned from Dundalk very excited about developments in terms of the identification of what I considered to be good suspects for the crime. To be honest, I was elated and could not wait to have them interviewed.”

When asked by Senator Walsh what should have been the next step to have been taken he responded:

“I believed we should have sought permission to go to Northern Ireland to put to the RUC, in synopsis form, the sequence of events, those we believed were involved, the terrain and so on in order to allow them to conduct the relevant interviews.”

He added that he had hoped the interviews would be carried out by the RUC and said “I was looking forward to that happening and was hoping to visit Northern Ireland within a week.” The Sub-Committee is of the view that this is important as it illustrates the suddenness with which the Garda investigation ceased at that time. In response to a question from Deputy Costello, former Detective Sergeant Corrigan stated that he had been “dumbfounded” when the former Detective Inspector Courtney had informed him that he had been on to C3 and that the matter (i.e. the interviewing of the suspects) was not being pursued. He said that he spoke to former Detective Inspector Courtney every second or third day and asked why no authorisation to travel North was forthcoming:

“When I pressed him to phone C3 again, first of all he said it was not being proceeded with and when I asked why he said former Commissioner Wren who was then in charge of C3, had said that it was not going ahead because if the four suspects were interviewed the RUC, as it was then known, would be looking for reciprocal arrangements with four IRA persons to be extradited North and that it was not going ahead for that reason.”

He stated that:

“I was so frustrated and annoyed that I did not want to discuss it with anyone. I felt very let down after having put in so much effort. We could not pursue the case and I was not aware that anyone else had information in that regard.”

He told the Sub-Committee that he would not have envisaged that he would go across the border to directly interview the suspects himself. He told the Sub-Committee that he had assumed that he and former Detective Inspector Courtney would travel North to provide information to the RUC to assist them in carrying out the actual interrogation. He told the Sub-Committee that such permission was not forthcoming. He was clear that C3 was the only part of An Garda Síochána that could issue an instruction to travel to Northern Ireland.

Submissions from other persons

- The testimony given by other persons who appeared before the Sub-Committee make the divergence in the above submissions even more stark.

- The Divisional Officer in Drogheda at that time, former Chief Superintendent Cotterell, was clear that the Gardaí could not leave their own jurisdiction without the permission of C3. He said he would not have been in a position to question the policies of C3. In response to a question from Deputy Murphy, former Chief Superintendent Cotterell stated that:

“The policy of not allowing gardaí to go to the North was not haphazard - that is definite”.

Former Chief Superintendent Cotterell explained to the Sub-Committee that:

“We would have to issue a written report and then receive permission to go there”.

- Former Chief Superintendent Cotterell told the Sub-Committee that he agreed that there was a difficulty with conducting interviews North of the border. His submission suggests that reciprocity was the difficulty:

“If we went to interview them up there they would be looking for all sorts of privileges down here. They were privileges they could not allow because they would not be accepted coming down.”

- In response to questions posed by Deputy Power in respect of the need to get C3 permission, former Chief Superintendent Cotterell stated that:

“I do not think you would need the permission for gardaí to go up to have a chat with RUC officers but interviewing suspects would be a horse of a different colour.”

- Former Detective Garda Hynes, who was involved in the investigation at the time, stated that he had been involved in a number of external investigations where the Gardai interviewed in the North, suspects and witnesses in respect of events that had taken place in the South. He stated that “As far as I am aware, the normal procedure was that when such journeys were made, permission had to be received from crime and security branch, or C3 as it was then known.” In respect of the 1953 directive he stated that he had never heard of it and that he had never heard it being discussed when arrangements were being made to travel abroad.

- Mr. Gerry Collins, Minister for Justice 1977 to 1981, in his submission to the Sub-Committee took the view that the RUC should have brought in these men, questioned them and if necessary, used the provisions of the Criminal Law (Jurisdiction) Act 1976 to try them in Northern Ireland. In response to questions from Senator Walsh in respect of the policy of not allowing interviews by Gardaí north of the border, Mr. Collins told the Sub-Committee:

“That was the policy of the day. My view was that it was the proper policy and it was one I supported totally and fully and if I was still there I would support it”.

He explained the background to the policy as follows:

“They wanted many things and they are matters of public knowledge, which are mentioned on page 84 of the Report. It is a question of the hot pursuit of suspects across the Border, which in my mind and the minds of the professionals within the Garda, would have been the height of folly in practice. Who would protect those who were pursuing the suspects from ambush? If they flew in spotter aeroplanes 800 feet or 1,000 feet across the Border, who would protect the small aeroplanes from being shot down? If they came and questioned suspects in Garda stations, who would protect them as they travelled in and out? There was no way the Government could have a situation where any of its agencies was involved in handing over persons who were suspects only and who were needed for questioning by the authorities in Northern Ireland. That was the policy of the day.”

He stated that he could not resolve any difference in the account of former Detective Inspector Courtney and former Commissioner Wren but added:

“I totally support everything former Commissioner Wren said. He is one of the finest, most honourable, principled people I have met in the police force. He is a man of the utmost probity and integrity who gave 44 very valuable years in the service of the State.”

- Former Assistant Commissioner Ainsworth was Deputy Commissioner in C3 from December 1979 to February 1983. He told the Sub-Committee that C3 had never been examined by management consultants at the time. He said that no correspondence in respect of the Ludlow murder had ever been brought to his notice. He was not aware of the 1953 directive at the time. He pointed out that nobody has authority to guillotine a murder investigation for non-statutory reasons and said that if he had been aware that this had occurred he would have raised the matter with the Commissioner. He added:

“Extradition is not a matter for the Garda Síochána, but the Government and the courts. The Garda investigates an accused person and places the papers before the proper legal authority for decision. What happens after that is determined by other forces, not by the Garda. The Garda examines and presents the case which thereafter develops. The Garda cannot take into consideration extraneous matters such as overflight incursions or extraterritorial inquiries because all these matters are purely political. A murder inquiry continues, even when nothing can be added to finalise the case. That has always been my approach to murder inquiries. The prime function of the Garda is the protection of life and property and a murder is a major Garda concern following the loss of life. The Garda is obliged to pursue a murder inquiry without interference. If a murder case becomes cold for any or numerous reasons, it should be independently reviewed by an independent investigator. That is how I see the development of a crime investigation. Dogmatic or persuasive directives stopping or curtailing an inquiry are valueless.”

- In response to questions from Deputy Costello, former Assistant Commissioner Ainsworth agreed that co-operation existed between the RUC and Gardaí but that it did not extend to being present while an interview was taking place in an RUC station. He said that the Ludlow file had never been given to him when he was in C3 and that this baffled him. He said he did not know anything about former Detective Inspector Courtney being stopped from continuing his investigation.

- John Fleming was Commissioner of C1 from 1977 to 1979. In a written submission to the Sub-Committee he stated that he never received any information in relation to the Ludlow murder. He said that between 1977 and 1979 “I had no knowledge of any member of the Garda travelling to Northern Ireland to investigate crime during that time”.

- In respect of the 1953 Directive, Garda Commissioner Conroy told the Sub-Committee that any such document would have been incorporated into the Garda Code in 1965. In response to a question from Senator Walsh, he informed the Sub-Committee that the 1965 Code did not contain anything specific to prohibit Gardaí from travelling outside the jurisdiction to interview suspects or assist another police force to do so. He drew a distinction between the Gardaí going North to request the RUC to investigate suspects and the Gardaí seeking to interview persons in the North themselves:

“There would have been no difficulties in requesting permission to go outside the State to assist another police service such as the RUC at the time in conducting investigations on behalf of the Garda Síochána. There is no way that our authorities, either then or now, would give permission to a member of the Garda Síochána to go to another jurisdiction and ask the police service to interview individuals suspected of having committed a crime. That would never happen. If Garda Headquarters was taken apart, I doubt if a document would ever be found which would state this”.

He said that C3 would have been a conduit in ensuring that everything was prepared and that officers were ready to travel.

- In respect of reciprocity, Commissioner Conroy stated:

“I could foresee a situation where, for reasons of which I am not aware, C3 may have refused permission to travel to Northern Ireland to conduct an investigation, namely, because reciprocal arrangements would have had to be put in place in the South. That is as far as I can go on that matter. I have not read anything in the documentation which suggests that was the case. I cannot, unfortunately, enlighten the Sub-Committee any further.”

- Minister McDowell offered the Sub-Committee his interpretation of the issues in the following terms:

“The Barron inquiry believes the only credible explanation for the non-pursuit of the suspects is that a direction was given that led the investigating officer to abandon plans to have the suspects interviewed outside the jurisdiction. I am afraid I am not in a position to adjudicate between the competing claims made by former members of the Garda Síochána on who did or did not give such a direction. I simply do not know how the decision not to interview the suspects was reached or what precisely formed the Garda’s thinking in this case. There is nothing in the files of the Department that relates to the identification of the four suspects in 1979.

I note that the Barron Report posits that the decision not to pursue the information offered by the RUC was made by the then Garda Commissioner, Mr. Laurence Wren. The Report goes on to speculate that before making the decision, it is likely that Mr. Wren would have discussed the matter with other senior gardaí and, possibly, senior officials from the then Department of Justice. The members of the Sub-Committee are aware from the report that the only surviving member of the Department’s security division which would have dealt with such matters at the time has no recollection of the case. As I said, there are no records in the Department from 1979 which deal with this topic. I will return to this aspect of the matter.

At this remove, there is no way that the Department or I can definitively state whether the Department was consulted by Mr. Wren or any other garda on the issue of the questioning of the suspects. I am sure Mr. Wren will want me to note that he strongly denies the findings of the report in this regard as they relate to him in their entirety. Having said that, I speculate that no such communication took place. My belief which can only be an educated surmise is based on two main reasons. First, there is no reason to believe the Department was notified in 1979 that four suspects had been identified by the RUC. There is certainly no documentary evidence that this was the case. Second, it is my understanding of the general relationship between the Department and the Garda that the investigation of criminal offences was a matter for the force within the legal and operational frameworks of the day. Although the Minister and the Department would have been briefed in general terms on the progress of major Garda investigations, they would have had no role in directing individual investigations.”

- Deputy Costello asked the Minister how the contradictory reports in respect of the policy could be reconciled. Minister McDowell emphasised again the assistance his Department was willing to provide and suggested the following:

“To return to what Deputy Peter Power said, if former Detective Garda Hynes identifies a particular case and date, it would be interesting to see whether there is a relevant paper trail in the Department throwing up material of the kind we now say does not exist. On the other hand, if it is established beyond any doubt that there was interviewing of witnesses north of the Border at the time in question, the matter of whether the Department was consulted is an issue from which the sub-committee might draw inferences in respect of other cases. I am speculating now and I am not really in a position to help very much. However, if a particular file or instance is identified, the Department will help by carrying out a search with a view to identifying whether there is a paper trail of consultation and whether there was departmental or ministerial involvement in other cases in similar circumstances”.

- Mr Sean Aylward, Secretary General of the Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform also assured the Sub-Committee that assistance on this matter would be forthcoming:

“Senior members of the Garda are checking out this to see what they can find. We will check it out also, but it is extremely recent evidence. One person has suggested that in some crime investigations there was direct interviewing of suspects and identified two or three cases where it was done directly. This runs counter to the evidence of very senior and respected individuals who have given evidence. There is a divergence on the specific point of directly interviewing suspects held in custody in Northern Ireland. We do not have information that sustains that assertion but it would be worth checking out. It is important to record the divergence which is considerable.”

- Former Commissioner Pat Byrne assisted the Sub-Committee by offering his views:

“The key question, in my view, that was asked of me by Mr. Justice Barron was framed in his letter to me which refers to steps taken as a consequence of intelligence received. In the letter he states that there was nothing on file to suggest that any such steps were taken. He asks whether this suggests no such steps were taken and, if so, where would the default lie. My synopsis would be that we had the information and he was asking what we did with it. Part of my reply as contained in the interim report reflects my view.

The over-arching issue in relation to this, as is contained in my report, is the awareness of people of that information which was first received by the Garda Síochána on 30 January 1979. Obviously those who were not aware of it cannot be faulted. In my report I refer to people in public life both in this State and in Northern Ireland who were aware of the information. I hasten to add, however, that irrespective of who knew what, the primary responsibility rested with the investigative authority at the time this crime was committed in this State, and that was the Garda Síochána.

In essence, in terms of what did or did not happen, the responsibility lay with the Garda Síochána, although it gives me no satisfaction to say that. To suggest otherwise would be ludicrous. At the end of the day, there was a systems failure for various reasons. As I stated in my report, having examined all paperwork and documentary evidence on this matter, I could not identify why what one would have expected to happen did not happen.”

He said that it was a human failure and that he had not been able to identify the individual persons responsible for the system failure which had occurred. It was one which he could not foresee happening again. He was of the view that a situation where four murder suspects were named but no steps were taken simply would not occur again.

- Former Commissioner Byrne said that he could not imagine a situation whereby members of the Garda Síochána would interview suspects who did not wish to be interviewed outside the State. The responsibilities and powers of the Garda Síochána only apply within the State. However he pointed out that there are a number of ways people can be interviewed, including having a suspect interviewed by another on one’s behalf. The key issue was therefore whether any further steps were taken, such as having the suspects interviewed by a different agency such as the Scottish police or RUC or, not interviewing them at all. Also, were there further meetings regarding intelligence, were discussions held with the DPP and was background information sought directly or indirectly in terms of establishing where the suspects were at a particular time? He said that C3 was the channel that one would use. He said he found it odd that the 1953 Directive, with which he had never been familiar, would be used to justify events which occurred over 20 years after it was written.

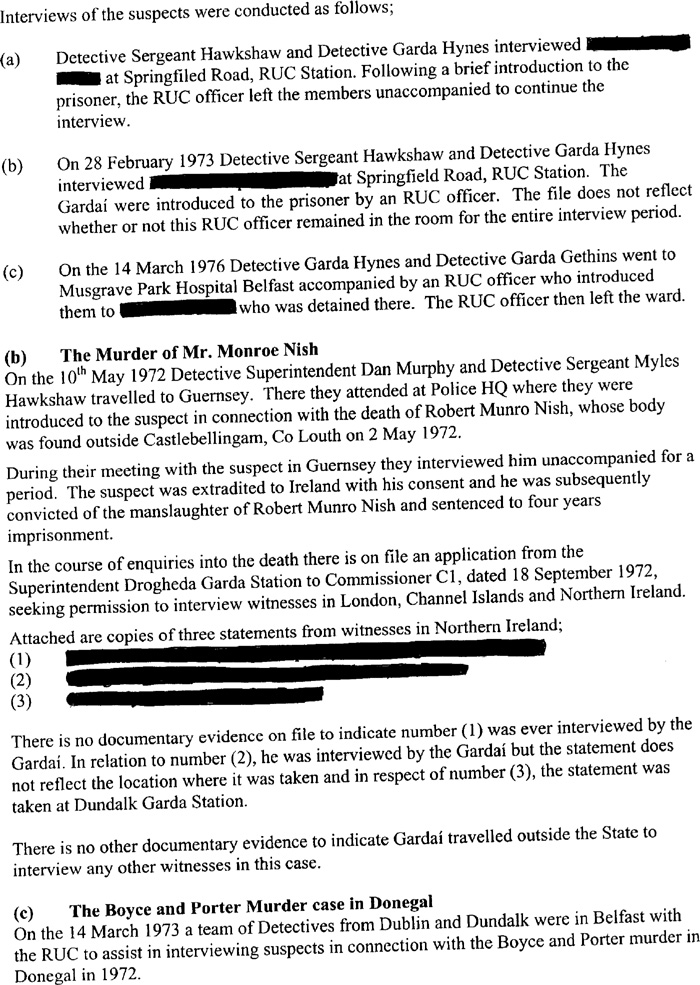

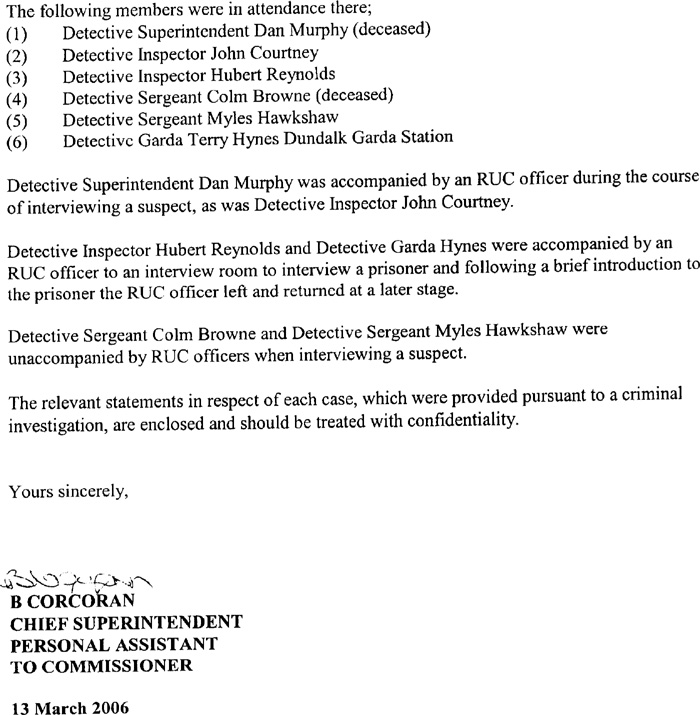

- The Sub-Committee has now however received information from Chief Superintendent Corcoran who is the Personal Assistant to the Garda Commissioner. The Garda Commissioner promised to assist the Sub-Committee by giving the Sub-Committee information and details on issues that might arise. In this regard, former Detective Garda Terry Hynes told the Sub-Committee of 3 separate incidents where he was aware that Gardai has travelled to Northern Ireland in connection with incidents that had taken place in this jurisdiction and on which occasions he believed interviews with suspects had taken place. Chief Superintendent Corcoran was able to confirm the following:

in respect of a robbery at Dundalk Railway Station in 1973, 2 Detective Gardai interviewed suspects in an RUC station, and on one occasion, in a hospital in Belfast in respect of a robbery at Dundalk Railway Station in 1973, 2 Detective Gardai interviewed suspects in an RUC station, and on one occasion, in a hospital in Belfast

in respect of the murder of Mr Monroe Nish in 1972, Detective Gardai travelled to Guernsey to interview a suspect and that permission was sought to travel to Northern Ireland to interview witnesses, and in respect of the murder of Mr Monroe Nish in 1972, Detective Gardai travelled to Guernsey to interview a suspect and that permission was sought to travel to Northern Ireland to interview witnesses, and

in respect of the Boyce and Porter murder case in Donegal in 1973, Detective Gardai interviewed suspects in Northern Ireland with the permission of the RUC and unaccompanied by the RUC. in respect of the Boyce and Porter murder case in Donegal in 1973, Detective Gardai interviewed suspects in Northern Ireland with the permission of the RUC and unaccompanied by the RUC.

This entire letter is included at Appendix A.

Other Precedents and The Livingstone Incident