Tithe an Oireachtais

An Comhchoiste um Dhlí agus Ceart, Comhionannas, Cosaint agus Cearta na mBan

Tuarascáil Eatramhach ar an Tuarascáil ón gCoimisiún Fiosrúcháin Neamhspleách faoi Bhuamáil Theach Tábhairne Kay, Dún Dealgan

Iúil, 2006

Houses of the Oireachtas

Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights

Interim Report on the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Bombing of Kay’s Tavern, Dundalk

July, 2006

(Prn. A6/1091)

Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights.

Interim Report on the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Bombing of Kay’s Tavern, Dundalk

Contents

Interim Report

Appendices

- Orders of Reference and Powers of the Joint Committee

- Membership of the Joint Committee

- Motions of Dáil Éireann and Seanad Éireann

- Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Bombing of Kay’s Tavern, Dundalk

Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights.

Interim Report on the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Bombing of Kay’s Tavern, Dundalk

The Joint Committee conveys its deepest condolences to the victims and families of the victims of the car bomb explosion on Crowe Street, Dundalk, outside Kay’s Tavern in December 1975; the gun and bomb attack which was carried out at Donnelly’s Bar, Silverbridge, Co. Armagh also in December of that year; the bombing at Dublin Airport in November 1975; the car bomb outside the Three Star Inn in Castleblayney, County Monaghan in March 1976; the explosion and murder at Barronrath Bridge, County Kildare in June 1975; the bomb at Swanlinbar, County Cavan in February 1976; the murders perpetrated between 1974 and 1976 at Dungannon, County Tyrone; at Castleblayney, County Monaghan; on the road to Newry, at Newtownhamilton and Whitecross in County Armagh; at Gilford, County Down; Charlemont; Ahoghill, County Antrim; and in the gun and bomb attack at Keady, County Armagh.

I, Seán Ardagh T.D., the Chairperson of the Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights, having been authorised by the Committee to submit this Report, do hereby present and publish a report of the Committee entitled ‘Interim Report on the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Bombing of Kay’s Tavern, Dundalk’.

This report was received by the Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights today Wednesday, 5th July, 2006.

In accordance with the referral motions by Dáil and Seanad Éireann today, the Committee has decided to establish a Sub-Committee to consider, including in Public session, the report and to report back to the Joint Committee, in order that the Joint Committee can report back to the Houses of the Oireachtas by 17th November 2006.

As part of the consideration of the report, the Committee intends that the Sub-Committee will invite submissions from interested persons and bodies and hold public hearings, in the Autumn of 2006, with a view to producing a final report on the matter. The report will detail submissions received, the hearings held, and such comments, recommendations or conclusions as the Committee may decide to make, and the said report will be published.

Seán Ardagh T.D.,

Chairperson,

5th July, 2006.

Appendix A

Orders of Reference

.JOINT COMMITTEE ON JUSTICE, EQUALITY, DEFENCE AND WOMEN’S RIGHTS.

Dáil Éireann on 16 October 2002 ordered:

-

- That a Select Committee, which shall be called the Select Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights, consisting of 11 Members of Dáil Éireann (of whom 4 shall constitute a quorum), be appointed to consider -

- such Bills the statute law in respect of which is dealt with by the Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform and the Department of Defence;

- such Estimates for Public Services within the aegis of the Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform and the Department of Defence; and

- such proposals contained in any motion, including any motion within the meaning of Standing Order 157 concerning the approval by the Dáil of international agreements involving a charge on public funds,

as shall be referred to it by Dáil Éireann from time to time.

- For the purpose of its consideration of Bills and proposals under paragraphs (1)(a)(i) and (iii), the Select Committee shall have the powers defined in Standing Order 81(1), (2) and (3).

- For the avoidance of doubt, by virtue of his or her ex officio membership of the Select Committee in accordance with Standing Order 90(1), the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform and the Minister for Defence (or a Minister or Minister of State nominated in his or her stead) shall be entitled to vote.

-

- The Select Committee shall be joined with a Select Committee to be appointed by Seanad Éireann to form the Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights to consider –

- such public affairs administered by the Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform and the Department of Defence as it may select, including, in respect of Government policy, bodies under the aegis of those Departments;

- such matters of policy for which the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform and the Minister for Defence are officially responsible as it may select;

- such related policy issues as it may select concerning bodies which are partly or wholly funded by the State or which are established or appointed by Members of the Government or by the Oireachtas;

- such Statutory Instruments made by the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform and the Minister for Defence and laid before both Houses of the Oireachtas as it may select;

- such proposals for EU legislation and related policy issues as may be referred to it from time to time, in accordance with Standing Order 81(4);

- the strategy statement laid before each House of the Oireachtas by the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform and the Minister for Defence pursuant to section 5(2) of the Public Service Management Act, 1997, and the Joint Committee shall be authorised for the purposes of section 10 of that Act;

- such annual reports or annual reports and accounts, required by law and laid before both Houses of the Oireachtas, of bodies specified in paragraphs 2(a)(i) and (iii), and the overall operational results, statements of strategy and corporate plans of these bodies, as it may select;

Provided that the Joint Committee shall not, at any time, consider any matter relating to such a body which is, which has been, or which is, at that time, proposed to be considered by the Committee of Public Accounts pursuant to the Orders of Reference of that Committee and/or the Comptroller and Auditor General (Amendment) Act, 1993;

Provided further that the Joint Committee shall refrain from inquiring into in public session, or publishing confidential information regarding, any such matter if so requested either by the body concerned or by the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform or the Minister for Defence;

- such matters relating to women’s rights generally, as it may select, and in this regard the Joint Committee shall be free to consider areas relating to any Government Department; and

- such other matters as may be jointly referred to it from time to time by both Houses of the Oireachtas,

and shall report thereon to both Houses of the Oireachtas.

- The quorum of the Joint Committee shall be five, of whom at least one shall be a Member of Dáil Éireann and one a Member of Seanad Éireann.

- The Joint Committee shall have the powers defined in Standing Order 81(1) to (9) inclusive.

- The Chairman of the Joint Committee, who shall be a Member of Dáil Éireann, shall also be Chairman of the Select Committee.”.

Seanad Éireann on 17 October 2002 ordered:

-

- That a Select Committee consisting of 4 members of Seanad Éireann shall be appointed to be joined with a Select Committee of Dáil Éireann to form the Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights to consider -

- such public affairs administered by the Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform and the Department of Defence as it may select, including, in respect of Government policy, bodies under the aegis of those Departments;

- such matters of policy for which the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform and the Minister for Defence are officially responsible as it may select;

- such related policy issues as it may select concerning bodies which are partly or wholly funded by the State or which are established or appointed by Members of the Government or by the Oireachtas;

- such Statutory Instruments made by the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform and the Minister for Defence and laid before both Houses of the Oireachtas as it may select;

- such proposals for EU legislation and related policy issues as may be referred to it from time to time, in accordance with Standing Order 65(4);

- the strategy statement laid before each House of the Oireachtas by the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform and the Minister for Defence pursuant to section 5(2) of the Public Service Management Act, 1997, and the Joint Committee shall be so authorised for the purposes of section 10 of that Act;

- such annual reports or annual reports and accounts, required by law and laid before both Houses of the Oireachtas, of bodies specified in paragraphs 1(a)(i) and (iii), and the overall operational results, statements of strategy and corporate plans of these bodies, as it may select;

Provided that the Joint Committee shall not, at any time, consider any matter relating to such a body which is, which has been, or which is, at that time, proposed to be considered by the Committee of Public Accounts pursuant to the Orders of Reference of that Committee and/or the Comptroller and Auditor General (Amendment) Act, 1993;

Provided further that the Joint Committee shall refrain from inquiring into in public session, or publishing confidential information regarding, any such matter if so requested either by the body concerned or by the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform or the Minister for Defence;

- such matters relating to women’s rights generally, as it may select, and in this regard the Joint Committee shall be free to consider areas relating to any Government Department;

and

- such other matters as may be jointly referred to it from time to time by both Houses of the Oireachtas.

and shall report thereon to both Houses of the Oireachtas.

- The quorum of the Joint Committee shall be five, of whom at least one shall be a member of Dáil Éireann and one a member of Seanad Éireann,

- The Joint Committee shall have the powers defined in Standing Order 65(1) to (9) inclusive,

JOINT COMMITTEE ON JUSTICE, EQUALITY, DEFENCE AND WOMEN’S RIGHTS.

POWERS OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE

The powers of the Joint Committee are set out in Standing Order 81(Dáil) and Standing Order 65 (Seanad). The text of the Dáil Standing Order is set out below. The Seanad S.O. is similar.

- Without prejudice to the generality of Standing Order 80, the Dáil may confer any or all of the following powers on a Select Committee:

- power to take oral and written evidence and to print and publish from time to time minutes of such evidence taken in public before the Select Committee together with such related documents as the Select Committee thinks fit;

- power to invite and accept written submissions from interested persons or bodies;

- power to appoint sub-Committees and to refer to such sub-Committees any matter comprehended by its orders of reference and to delegate any of its powers to such sub-Committees, including power to report directly to the Dáil;

- power to draft recommendations for legislative change and for new legislation and to consider and report to the Dáil on such proposals for EU legislation as may be referred to it from time to time by any Committee established by the Dáil(whether acting jointly with the Seanad or otherwise) to consider such proposals and upon which has been conferred the power to refer such proposals to another Select Committee;

- power to require that a member of the Government or Minister of State shall attend before the Select Committee to discuss policy for which he or she is officially responsible: provided that a member of the Government or Minister of State may decline to attend for stated reasons given in writing to the Select Committee, which may report thereon to the Dáil: and provided further that a member of the Government or Minister of State may request to attend a meeting of the Select Committee to enable him or her to discuss such policy;

- power to require that a member of the Government or Minister of State shall attend before the Select Committee to discuss proposed primary or secondary legislation (prior to such legislation being published) for which he or she is officially responsible: provided that a member of the Government or Minister of State may decline to attend for stated reasons given in writing to the Select Committee, which may report thereon to the Dáil: and provided further that a member of the Government or Minister of State may request to attend a meeting of the Select Committee to enable him or her to discuss such proposed legislation;

- subject to any constraints otherwise prescribed by law, power to require that principal office holders in bodies in the State which are partly or wholly funded by the State or which are established or appointed by members of the Government or by the Oireachtas shall attend meetings of the Select Committee, as appropriate, to discuss issues for which they are officially responsible: provided that such an office holder may decline to attend for stated reasons given in writing to the Select Committee, which may report thereon to the Dáil;

- power to engage, subject to the consent of the Minister for Finance, the services of persons with specialist or technical knowledge, to assist it or any of its sub-Committees in considering particular matters; and

- power to undertake travel, subject to—

- such rules as may be determined by the sub-Committee on Dáil Reform from time to time under Standing Order 97(3)(b);

- such recommendations as may be made by the Working Group of Committee Chairmen under Standing Order 98(2)(a); and

- the consent of the Minister for Finance, and normal accounting procedures.”.

SCOPE AND CONTEXT OF COMMITTEE ACTIVITIES.

The scope and context of activities of Committees are set down in S.O. 80(2) [Dáil] and S.O.64(2) [Seanad]. The text of the Dáil Standing Order is reproduced below. The Seanad S.O. is similar.

- It shall be an instruction to each Select Committee that-

- it may only consider such matters, engage in such activities, exercise such powers and discharge such functions as are specifically authorised under its orders of reference and under Standing Orders;

and

- such matters, activities, powers and functions shall be relevant to, and shall arise only in the context of, the preparation of a report to the Dáil.”

Appendix B

JOINT COMMITTEE ON JUSTICE, EQUALITY, DEFENCE AND WOMEN’S RIGHTS

List of Members |

Deputies |

Seán Ardagh (FF) (Chairperson) |

|

Máire Hoctor (FF) (Government Convenor) |

|

Brendan Howlin (LAB) |

|

Kathleen Lynch (LAB) (Opposition Convenor) |

|

Finian McGrath (Independent/ Technical Group) |

|

Gerard Murphy (FG) (Vice-Chairperson) |

|

Charlie O’Connor (FF) |

|

Denis O’Donovan (FF) |

|

Seán O’Fearghaíl (FF) |

|

Jim O’Keeffe (FG) |

|

Peter Power (FF) |

Senators |

Maurice Cummins (FG) |

|

Tony Kett (FF) |

|

Joanna Tuffy (LAB) |

|

Jim Walsh (FF). |

Appendix C

Motions of the Dáil and Seanad

Go n-iarrann Dáil Éireann ar an gComhchoiste um Dhlí agus Ceart, Comhionannas, Cosaint agus Cearta na mBan, nó ar Fhochoiste den Chomhchoiste sin, breithniú a dhéanamh, lena n-áirítear breithniú i seisiún poiblí, ar an Tuarascáil ón gCoimisiún Fiosrúcháin Neamhspleách faoi bhuamáil Kay’s Tavern, Dún Dealgan, chun cibé moltaí a dhéanamh i ndáil le forálacha reachtaíochta nó riaracháin is cuí leis an gCoiste, agus tuairisc a thabhairt do Dháil Éireann faoin 17 Samhain, 2006.

That Dáil Éireann requests the Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights, or a sub-Committee thereof, to consider, including in public session, the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Bombing of Kay’s Tavern, Dundalk, for the purpose of making such recommendations in relation to legislative or administrative provisions as the Committee considers appropriate, and to report back to Dáil Éireann by 17th November, 2006.

“Go n-iarrann Seanad Éireann ar an gComhchoiste um Dhlí agus Ceart, Comhionannas, Cosaint agus Cearta na mBan, nó ar Fhochoiste den Chomhchoiste sin, breithniú a dhéanamh, lena n-áirítear breithniú i seisiún poiblí, ar an Tuarascáil ón gCoimisiún Fiosrúcháin Neamhspleách faoi bhuamáil Kay’s Tavern, Dún Dealgan, chun cibé moltaí a dhéanamh i ndáil le forálacha reachtaíochta nó riaracháin is cuí leis an gCoiste, agus tuairisc a thabhairt do Sheanad Éireann faoin 17 Samhain, 2006.

That Seanad Éireann requests the Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights, or a sub-Committee thereof, to consider, including in public session, the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Bombing of Kay’s Tavern, Dundalk, for the purpose of making such recommendations in relation to legislative or administrative provisions as the Committee considers appropriate, and to report back to Seanad Éireann by 17th November, 2006.”

REPORT OF THE INDEPENDENT COMMISSION OF INQUIRY INTO THE BOMBING OF KAY’S TAVERN, DUNDALK

PRESENTED TO AN TAOISEACH, BERTIE AHERN,

FEBRUARY 2006

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE

PART ONE – BACKGROUND INFORMATION

- HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

- THE BOMBING OF KAY’S TAVERN, DUNDALK

PART TWO – THE GARDA INVESTIGATION

- EYEWITNESS INFORMATION

- THE FORENSIC INVESTIGATION

- INTELLIGENCE INFORMATION

- THE INVESTIGATION REPORTS AND FURTHER INQUIRIES

PART THREE – ASSESSMENT OF THE INVESTIGATION

- THE WORK OF THE COMMISSION

- THE GARDA INVESTIGATION

PART FOUR – THE PERPETRATORS AND POSSIBLE COLLUSION

- OVERVIEW

- INFORMATION CONCERNING LOYALIST PARAMILITARY GROUPS

- INFORMATION CONCERNING INDIVIDUAL SUSPECTS

- ALLEGATIONS OF COLLUSION

PART FIVE – CONCLUSIONS

APPENDICES

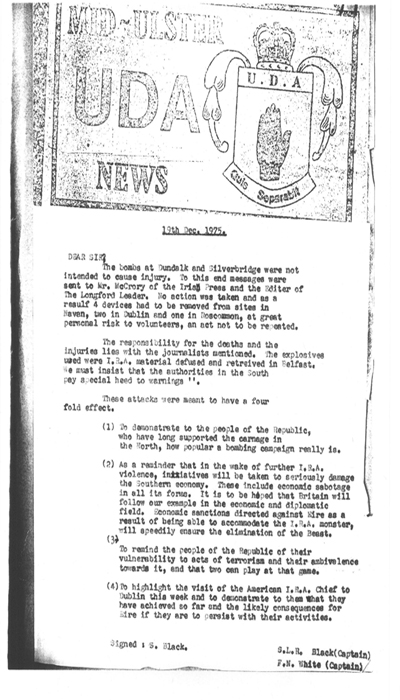

- CLAIM OF RESPONSIBILITY BY ‘MID-ULSTER UDA’

- BOMBING OF DUBLIN AIRPORT

- BOMBING OF 3 STAR INN, CASTLEBLAYNEY

- ATTACK ON MIAMI SHOWBAND

- EXPLOSION AND MURDER AT BARRONRATH BRIDGE, CO. KILDARE

- OTHER BOMBINGS IN THE STATE, 1974-76

- INFORMATION CONCERNING CERTAIN WEAPONS

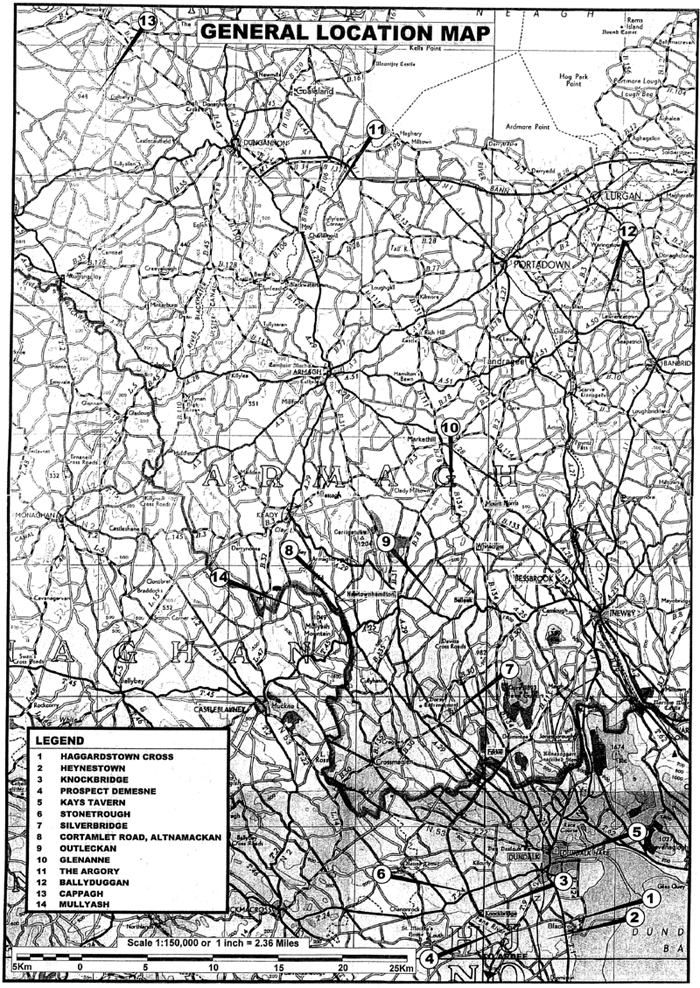

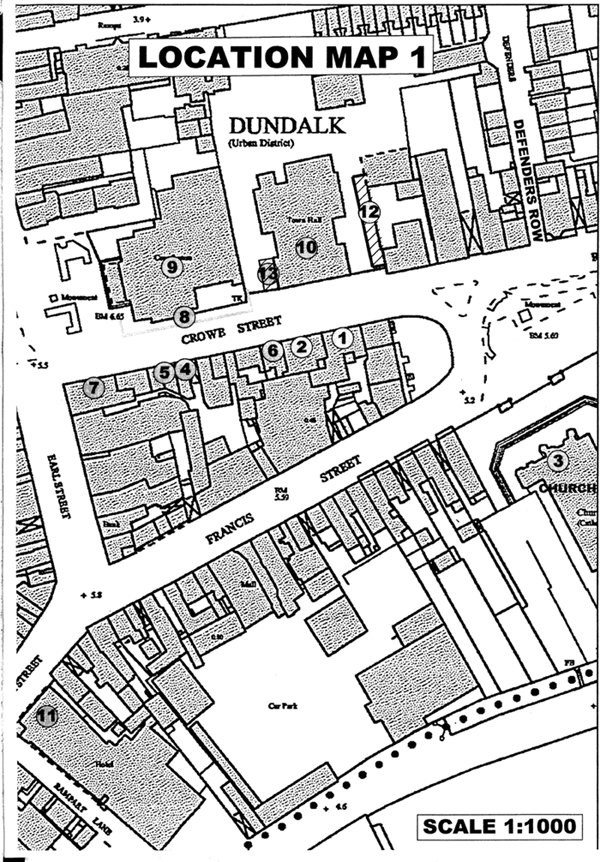

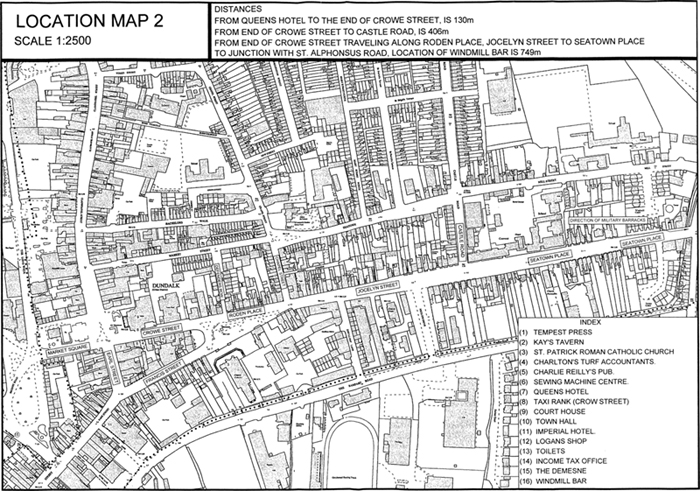

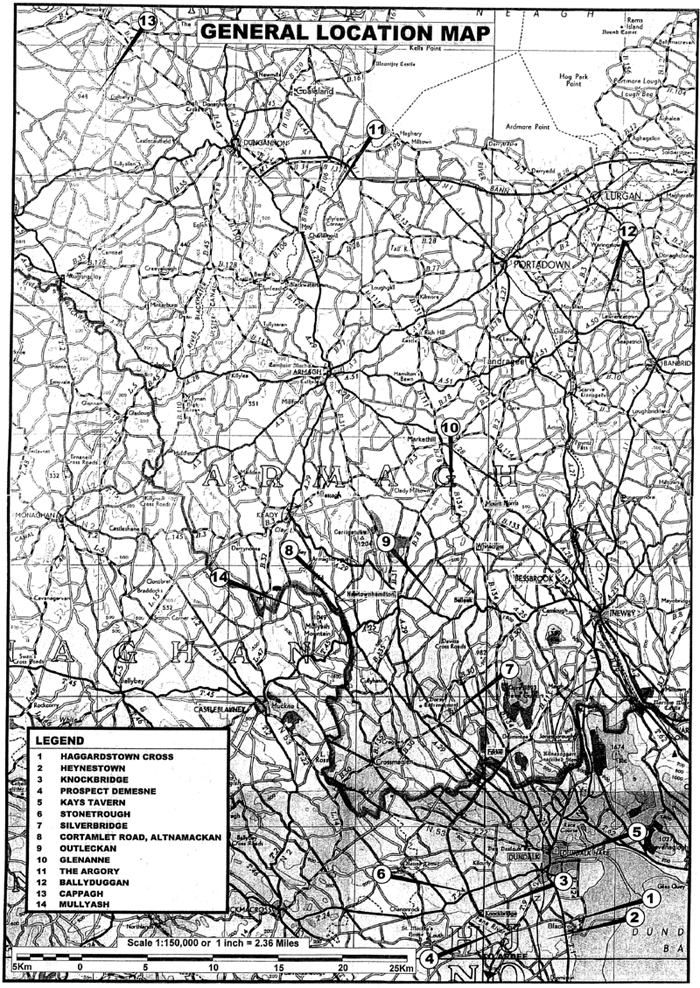

- MAPS

PREFACE

BOMBING OF KAY’S TAVERN, DUNDALK:

On the evening of 19 December 1975, a car bomb exploded on Crowe Street, Dundalk, outside a licensed premises known as Kay’s Tavern. Two people were killed in the explosion, and many more were injured. Later that same evening, a gun and bomb attack was carried out at Donnelly’s Bar, Silverbridge, Co. Armagh, in which three people were killed. Police on both sides of the border believed the two attacks were linked.

The ensuing Garda investigation into the Dundalk bombing was unable to find sufficient evidence to charge anyone in relation to the attack.

THE VICTIMS’ COMMISSION:

On 10 April 1998, an agreement, known as the ‘Good Friday Agreement’ was reached as a result of multi-party talks under the Chairmanship of United States Senator George Mitchell, former Finnish Prime Minister Harri Holkeri and Canadian General John de Chastelain. The Agreement was ratified by popular referendum in this State and in Northern Ireland on 22 May of that year.

In response to sections of the Agreement that proclaimed the need for the suffering of victims of violence to be recognised and addressed, a Victims Commission was set up in this State. It was asked:

“To conduct a review of services and arrangements in place, in this jurisdiction, to meet the needs of those who had suffered as a result of violent action associated with the conflict in Northern Ireland over the past thirty years and to identify what further measures need to be taken to acknowledge and address the suffering and concerns of those in question.”1

In a report published in July 1999, it was acknowledged that there was a widespread demand to find out the truth about specific crimes for which no one had been made amenable. Foremost among these were the Dublin and Monaghan bombings of 1974, but the Commission received similar submissions in relation to other bombings in Dublin, Dundalk and elsewhere. The murder of Seamus Ludlow on 1 May 1976 was another case singled out for mention in the report.

Concerning the Dublin / Monaghan bombings and the Ludlow murder, the report recommended that a former Supreme Court judge be asked to enquire privately into these matters. In relation to other cases of concern, it stated:

“There are other cases in which the families of victims have experienced similar concerns to those of the Dublin-Monaghan group and the Ludlow families. The fact that no prosecutions took place and that no official report on the crimes was ever made public has caused some families to question whether investigations have been adequate. I believe that it is in the broad public interest and in the interest of the Garda Síochána themselves that some answers be given….

I recommend that the Government, taking heed of the need to preserve the confidentiality and safety of informants, should, on request from the families of victims, produce reports on the investigations of murders arising from the conflict over the last 30 years where no one has been made amenable.”2

THE COMMISSION OF INQUIRY:

Arising from the recommendations of the Victims Commission, the Government set up the present Commission of Inquiry with former Chief Justice Liam Hamilton as Sole Member. Mr Hamilton began his duties on 1 February 2000 but was forced to resign on 2 October 2000, owing to ill health. The Government appointed former Supreme Court judge Henry Barron, in his place.

Initially, the Inquiry received terms of reference in relation to two incidents – the Dublin / Monaghan bombings of 17 May 1974 and the bombing of Kay’s Bar, Dundalk on 19 December 1975. The terms of reference in relation to the Dundalk investigation were as follows:

“To undertake a thorough examination, involving fact finding and assessment, of all aspects of the Dundalk bombing and its sequel, including the facts and circumstances of, and the background to, the bombing, having regard to the Garda investigation of the bombing, including the co-operation with and from the relevant authorities in Northern Ireland.

The ‘Dundalk bombing’ refers to the bomb explosion that took place in Dundalk on 19 December 1975.”

In the course of its work on the Dundalk bombing, the Inquiry has been given a certain amount of information concerning other subversive attacks which took place in the State between 1974 and 1976. The Inquiry has included information on a number of these incidents in the appendices which are to be found at the end of this report. This has been done in response to a request from the Government that the Inquiry, where possible, take account of other bombing incidents that took place within the State during the relevant period.

PART ONE

BACKGROUND INFORMATION

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

- GOVERNMENT AND SECURITY

- PARAMILITARY GROUPS

- INTELLIGENCE INFORMATION

The following account of events in Northern Ireland during 1975 and 1976 is not comprehensive. It is included with a view to illustrating the social and political background to the main events with which this Report is concerned.

GOVERNMENT AND SECURITY:

The year 1974 had witnessed considerable political upheaval in Northern Ireland, including the Ulster Workers Council strike, the demise of the Sunningdale Agreement, the collapse of the Northern Ireland Assembly and the reintroduction of direct rule from Westminster. Political developments in the years 1975 / 76 were not as dramatic.

Following the publication of several discussion papers on power-sharing by the Northern Ireland Office, elections were held in May 1975 for a Constitutional Convention. The United Ulster Unionist Council (UUUC) won 47 of the 78 available seats. Although a series of inter-party talks were held under the auspices of the Convention, no agreement could be reached on a form of power-sharing government for Northern Ireland. In October 1975, Vanguard Party leader William Craig was expelled from the UUUC for advocating a coalition with the nationalist SDLP. In March 1976, the British Government brought the Convention to an end, accepting the continuance of direct rule for the foreseeable future.

This period also saw the British Government adopt a policy of ‘normalisation’ towards Northern Ireland. Steps were taken to increase the role and resources of the RUC in tackling subversive crime, with the aim of reducing the Army’s role in policing. On 25 March 1976, Secretary of State Merlyn Rees told the House of Commons that primacy in security matters had been returned to the RUC.

A different approach was also taken towards paramilitary groups: three weeks earlier, Secretary of State Rees had announced that persons convicted of subversive crimes would no longer be entitled to special category status, but would be treated as ordinary criminals. The phasing out of internment during 1975 could also be seen as part of this normalisation process.

In March 1976, the Irish Government referred allegations of the ill-treatment of internees in Northern Ireland to the European Commission on Human Rights. In September of that year, the Commission found that interrogation techniques used by the Security Forces were in breach of the European Convention on Human Rights, and referred the matter to the Court for a ruling.

Notwithstanding the shift in policy which resulted in the RUC being given primacy in security matters, the British Army retained a significant presence in Northern Ireland during 1975 / 76. There remained certain areas in which the police and UDR did not patrol, and other areas in which an Army presence was required to protect the police as they carried out their duties. In January 1976, the first officially acknowledged deployment of an SAS unit took place in South Armagh, though it was widely believed that SAS members had been operating undercover in Northern Ireland for some time before this.

The UDR increased in size and resources, but remained unable to gain the trust of the nationalist community. Relations between the UDR and the RUC were also affected by the perception of the UDR as a compromised force. Suspicions were reinforced by a number of attacks carried out by persons wearing UDR uniforms, and by the conviction of UDR members for a number of offences including the Miami Showband murders.3

PARAMILITARY GROUPS:

The year 1975 began with the Provisional IRA announcing an extension to its ceasefire which began on 22 December 1974. This came to an end on 17 January; but following negotiations with the British authorities, a new ceasefire was announced on 10 February. Despite this, incidences of republican violence continued to occur. Some of them were the result of a feud between the Official IRA and the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA). Other attacks, such as the killing of four British soldiers near Forkhill, County Armagh on 17 July 1975, were clear breaches of the truce, though they were claimed to have been acts of retaliation for murders of Catholics by the Security Forces or by loyalist paramilitaries.

As 1975 progressed, the number of sectarian killings multiplied as loyalist and republican subversives engaged in “tit-for-tat” attacks, often targeting innocent civilians. Many of these attacks took place in the so-called ‘Murder Triangle’ – encompassing the towns of Portadown, Armagh, Dungannon and surrounding areas.4

A number of sectarian murders in the Belfast and Newtowhamilton areas during the summer of 1975 were claimed by the Protestant Action Force – a name believed to be no more than a cover for UVF activity.

In Belfast, an ongoing feud between the UDA and UVF resulted in several shootings. A similar feud between the Official and Provisional IRA resulted in 11 deaths in the first two weeks of November 1975.

On 5 September 1975, the Provisional IRA resumed its bombing campaign in England, killing two people with a bomb at the Hilton Hotel, London. Other bomb attacks in London and Caterham, Surrey followed later in the month.

On 22 September 1975, a number of bomb attacks took place in towns across Northern Ireland. The IRA claimed responsibility for some of these. Perhaps in retaliation for this, the UVF launched a series of gun and bomb attacks across Northern Ireland on 2 October. The attacks left twelve people dead, including four UVF members who died when a bomb they were transporting exploded prematurely near Coleraine, Co. Derry. In total, 13 bombs were planted by the UVF on that day. The British Government responded immediately by placing the UVF on the list of proscribed organisations.

The year 1976 began with a number of particularly savage attacks on civilians by both sides. In separate attacks on 4 January, loyalist gunmen shot and killed members of the Reavey and O’Dowd families.5 The following evening, republican paramilitaries operating a bogus military checkpoint near Kingsmills, Co. Armagh opened fire on a minibus bringing textile workers home from the factory where they worked. Ten people were killed. A telephone caller claimed the attack was the work of the “South Armagh Republican Action Force”, and said it was in retaliation for the Reavey and O’Dowd attacks of the previous evening. It was this incident which led the British Government to announce publicly that an SAS unit was being sent into South Armagh.

On 9 January, a Catholic priest from the Portadown area wrote to Prime Minister Harold Wilson and others concerning the security situation in the Murder Triangle. He highlighted twenty-one murders that had taken place in the area between July 1972 and January 1976, all of which bar one were said to remain unsolved. The victims were either Catholic themselves, or from Catholic families. The priest inferred from this that the RUC were being deliberately negligent in pursuing loyalist killers.

In February 1976, the death of IRA hunger-striker Frank Stagg in Wakefield Prison, England caused riots in Belfast and Derry.

On 7 March 1976, a car bomb outside the Three Step Inn, Castleblayney killed one passerby. Further gun and bomb attacks by loyalist paramilitaries on the Golden Pheasant Inn, Lisburn, and the Hillcrest Pub, Dungannon, resulted in six more deaths. The Provisional IRA also continued its campaign of violence, shooting former UDA spokesman Sammy Smyth in Belfast, and killing three British soldiers with a land-mine near Belleek, Co. Armagh, amongst other attacks.

On 22 May 1976, the UVF announced the beginning of a three-month ceasefire, which was in fact broken on a number of occasions with attacks in Belfast and elsewhere.

INTELLIGENCE INFORMATION:

As was mentioned in its Report on the Dublin and Monaghan Bombings, the Inquiry was given full access to Irish Army Intelligence reports of meetings with British Intelligence sources and to files of telegrams sent and received during the 1970s. It must be emphasised, as before, that these documents (and the quotations which follow in this section) are taken from Irish Army reports of what was said at the meetings. They are not direct quotes from transcripts or from British Intelligence documents.

Following a meeting in January 1975, it was reported:

“There is no current intelligence on the UVF other than that they in common with the UDA are experiencing leadership problems. A resumption of violence by the PIRA would influence the UVF towards cross-border activities.”

One month later, UVF militancy was reported as increasing, manifesting itself in a number of letter-bomb attacks. A report of 15 March 1975 referred to the UDA / UVF feud.

On 19 April 1975 it was reported:

“There are considerable political manoeuverings going on within the Loyalist paramilitary groups - the UDA, UVF and RHC” - but rank and file refuse to accept any non-military course of action…

The feud between the UDA and UVF has not helped discipline in either organisation. Many rank and file members are carrying out unauthorised operations independently of the leadership.... The leaders of both organisations are doing their best to exercise control over their members but they are patently unable to do so, although the UDA is the less indisciplined of the two groups.... The feud has been restricted generally to areas in North and East Belfast.”

The report of a meeting in June 1975 stated:

“[An] element of the UVF operating under the nom-de-guerre of Protestant Action Committee is responsible for most of the sectarian violence on the Protestant side. Loyalist paramilitary movements are re-organising their structures, recruiting and training in a great number of areas. New units are being formed in areas where they have not existed for a long time. There is probably some re-supply continuing, but no actual evidence of this has been obtained.”

In September 1975 it was reported that the UDA and UVF “have parted company completely.” The UDA were said to be “totally against the UVF sectarian assassinations which they see as the seeds of civil war.” The report continued:

“Generally speaking the UVF / UDA are not as well-equipped as was thought originally due to the fact that they have no secure base…

The ability of the UVF to engage in cross-border activities is very limited and our patrol arrangements frighten them off.”

At a meeting in November 1975 it was said that only “fringe elements” of the UDA were militarily active, with the exception of “one minor bomb team” who were acting independently of the leadership. As for the UVF, it was said that a number of “good arrests” of UVF members were made after the organization was proscribed, following its bombing offensive on 2 October. Twenty of those arrested were said to have been charged, “including some of the leaders...” It was not indicated whether these charges related simply to UVF membership or to more serious offences. The report of this meeting concluded:

“They [the UVF] are not well armed and their military capability is small. They still have a capability for intermittent bombing in the Republic.”

The bombing of Kay’s Tavern, Dundalk on 19 December 1975 was referred to in the report of a meeting dated 10 January 1976, which stated:

“It is not known who approved of the bombing… but it is thought that it was done on the initiative of a small group within the UVF.”

One month later it was reported that the UVF “hard-line” had moderated somewhat, but that “they need to be closely watched because they have their eyes on the Republic and are including Border towns on their list of targets.”

The first explicit mention of the Mid-Ulster UVF in the reports of meetings with British Intelligence sources came on 24 April 1976, when it was stated:

“The capacity of the Loyalist paramilitaries for violence is not very high - much less than the PIRA - because supplies are their real problem. Mid-Ulster UVF is the most active of the paramilitary groups and this has links with the Shankill UVF. The Mid-Ulster gang is using chemicals and fertilisers with commercial explosives to stretch their supplies.”

The report also referred to

“… some mavericks within the organization who insist on using violence and these cannot be controlled. These elements got ideas, support and assistance from other smaller groups like the Red Hand etc.... They were preparing for a bombing in Border towns on weekend 25 April.”

It is not clear from the report whether these maverick elements came from mid-Ulster or elsewhere. However, on 17 June 1976 it was reported that:

“UVF elements in the Dungannon-Portadown area tend to take independent action and would respond to PIRA attacks if at all possible…

[The] leader of the UVF, does not have effective control of some elements in Shankill and Mid-Ulster. The Mid-Ulster element seems to have little difficulty in getting supplies of explosives.”

On 4 September 1976 it was reported:

“The UVF is composed of a number of independent gangs and has suffered serious losses through arrests and loss of weapons. Fourteen members have been charged recently with various offences. Fifteen weapons as well as ammunition were seized by the Security Forces. Tests carried out on these weapons showed that one of them was involved in eleven shootings. Some of the leaders have left the North and gone to Scotland. The UVF still manages to get explosives and their policy continues to be oriented towards retaliatory attacks in the Republic. The bombing of the Catholic public house in Keady on 16 August 1976 (2 killed, 17 injured) was not authorised by the UVF: it was intended for the Republic instead.”

THE BOMBING

- THE EXPLOSION

- VICTIMS

- CLAIMS OF RESPONSIBILITY

THE EXPLOSION:

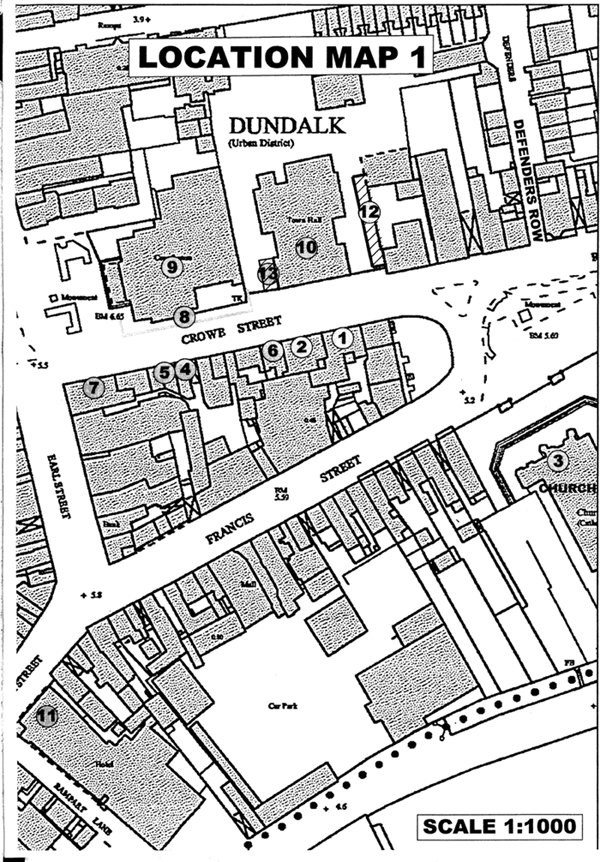

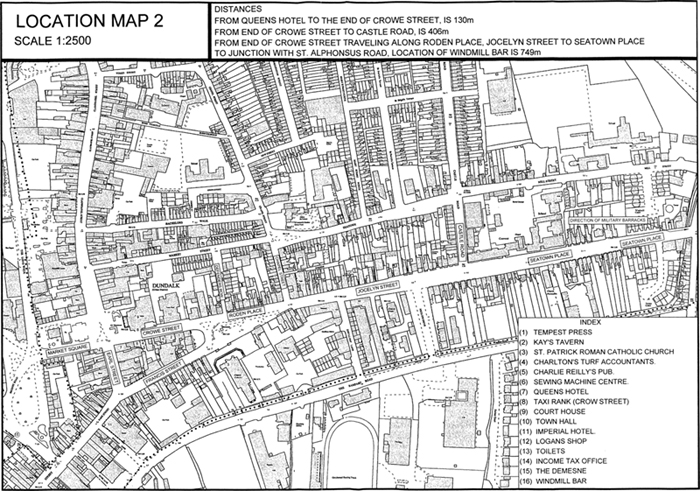

At 6.20 p.m. on Friday 19 December 1975, a car bomb exploded outside a licensed premises known as ‘Kay’s Tavern’, or ‘Kay Mulligan’s’. The pub was situated on the south side of Crowe Street in the centre of Dundalk town. The building itself was completely demolished by the explosion, and extensive damage was caused to parked vehicles and neighbouring buildings.

From the evidence of eyewitnesses, and the position of the crater in the road caused by the explosion,6 it appears that the car was parked close to the kerb outside the entrance to Kay’s bar. It was facing towards Roden Place. The explosion obliterated the back end of the vehicle, leaving just the two front wheels with portions of the engine and chassis. This suggests the bomb was located in the boot.

At the time of the explosion, Kay’s Tavern was relatively quiet, with just seven customers being served by the proprietor’s son, John McErlean. The proprietor herself, Mrs Kathleen McErlean, was upstairs in her living quarters with daughters Catherine and Alice. Had the pub been busier, the death toll would almost certainly have been higher. As it was, two people were killed: one a customer in the bar, the other a man on the street outside the bar door. More than twenty others were injured.

The explosion was of considerable force. A passer-by who was on the opposite side of the street, about twenty yards from the explosion when it occurred, was propelled into the air: he landed inside the railings of the Courthouse, some thirty yards away from where he had been. Inside Kay’s Tavern itself, two men who had been sitting on stools at the bar were propelled through the back wall of the bar and into the toilets, which were in the back yard. Another customer described the explosion as follows:

“Just at that I was thrown against a wall. I could feel what felt like waves hitting me. The bar burst into flames immediately… I saw a heavily built man, about 60 years. He was bleeding badly from the head. I grabbed him and headed towards the back of the bar… I made my way to what I thought was the entrance to the toilet. It turned out to be a dead end… We were still close to the bar. Myself and this man turned to go elsewhere and at that the bar exploded. I think this was the spirits exploding. I eventually made my way out to a window at the front of the building. I was taken by one of the firemen.”7

The first Garda officer to arrive at the scene was Sergeant Dan Prenty, at about 6.23 p.m. He stated:

“The bomb had exploded some minutes prior to my arrival there and the street was in a state of complete panic and disorder. I assisted in the rescue efforts there and was in control of the general area and scene until 8 p.m. The clock on the Town Hall was stopped at 6.20 p.m.”8

Although the Fire Brigade was on the scene promptly, it was about an hour before the fire was brought under control. Rescue workers then dug through the rubble looking for bodies:

“With the help of searchlights mounted on Fire Brigade hoists and excavators, they sifted through all the rubble and moved it into the streets. Nothing was found.”9

A roster of Gardaí were tasked with preserving the scene until 6 p.m. on the following day. At around 9 p.m. on the evening of the bombing, the scene was visited by Minister for Defence Patrick Donegan and the Garda Commissioner, Eamon Garvey. On the following morning the Minister for Justice Patrick Cooney visited the scene, also accompanied by the Garda Commissioner.

VICTIMS:

The two men who died as a result of the bombing were Hugh Watters, 60 years, married with grown-up children, and Jack Rooney, 62 years, also married with grown-up children.

Hugh Watters was a tailor, with premises in nearby Francis Street. He was a regular customer at Kay’s, calling in most evenings after work. He had no extreme political leanings. A witness who entered the bar a few minutes before the explosion recalled that he was sitting on his own at the rear of the bar, and was “in his usual jolly form”.10 At 6.45 p.m. his body was pulled from the burning premises by a fireman and a Garda officer. He was transported to Louth County Hospital, Dundalk, but was pronounced dead on arrival.

Jack Rooney was employed as a lorry driver / refuse collector with Dundalk Urban District Council. He did not hold any extreme political views. According to one of his colleagues, they had finished work at about 4 p.m. The team went for a pre-Christmas drink in McEneaney’s bar in Jocelyn Street. Jack, the witness and another man then took the lorry to the dump to empty it, returning to the Council yard at around 5.15 p.m. Jack and the witness went into the Condel Bar, Roden Place.

“Jack bought [another man] and myself a drink, he did not have one himself. This was before he left. I asked him to stay for another drink and he said that he had to walk home, get cleaned up, that he was going to Benny Brady’s on that night. Jack walked out the door at about 6.20 p.m. or so, he was quite sober. Jack had left the bar about a minute or less when I heard a very loud explosion.”11

When Kathleen McErlean came out of her premises following the explosion, she saw Jack Rooney lying on the footpath outside the door of the bar, badly injured. He was removed to the hospital shortly afterwards. Three days later, on 22 December, he died as a result of his injuries.

CLAIMS OF RESPONSIBILITY:

It would seem that no warnings were received prior to the bomb attack. On the following day, some Belfast newspapers received telephone calls claiming that the Red Hand Commandos had been responsible for the Dundalk bombing and for an attack on Donnelly’s Bar, Silverbridge, Co. Armagh on the same night.

Some days later, copies of a document purporting to be an extract from the ‘Mid-Ulster UDA News’ were received by a number of newspapers in the State, including the Irish Press and the Irish Times. According to the latter,

“The photostat statement, which was headed ‘Mid-Ulster UDA News’ and carries a UDA emblem, was posted in Armagh to the Irish Times on December 19th. It is unclear whether the statement was on ‘Mid-Ulster UDA News’ notepaper as the masthead of the periodical could have been cut off and attached above the statement and then photostated.”

From the copy on Garda files, it seems likely that this was the case. The UDA heading and emblem is at an angle to the rest of the statement, and the print is of a different quality.12 Of course, this does not prove that the document did not issue from the perpetrators: if indeed it was posted on the 19th, those who sent it must surely have known in advance of the plans to attack Dundalk and Silverbridge.

The statement, which took the form of a letter, read as follows:

“19th Dec. 1975.

Dear Sir

The bombs at Dundalk and Silverbridge were not intended to cause injury. To this end messages were sent to […] of the Irish Press and the Editor of the Longford Leader. No action was taken and as a result 4 devices had to be removed from sites in Navan, two in Dublin and one in Roscommon, at great personal risk to volunteers, an act not to be repeated.

The responsibility for the deaths and the injuries lies with the journalists mentioned. The explosives used were IRA material defused and retreived [sic] in Belfast. We must insist that the authorities in the South pay special heed to warnings.

These attacks were meant to have a four-fold effect.

- To demonstrate to the people of the Republic, who have long supported the carnage in the North, how popular a bombing campaign really is.

- As a reminder that in the wake of further IRA violence, inxxitiatives [sic] will be taken to seriously damage the Southern economy. These include economic sabotage in all its forms. It is to be hoped that Britain will follow our example in the economic and diplomatic field. Economic sanctions directed against Eire as a result of being able to accommodate the IRA monster will speedily ensure the elimination of the Beast.

- To remind the people of the Republic of their vulnerability to acts of terrorism and their ambivalence towards it, and that two can play at that game.

- To highlight the visit of the American IRA Chief to Dublin this week and to demonstrate to them what they have achieved so far and the likely consequences for Eire if they are to persist with their activities.

Signed: S. Black.

S.L.R. Black (Captain)

F.N. White (Captain)”

There is no evidence that the warnings referred to in the statement were in fact given. Gardaí interviewed a named journalist from the Irish Press as well as the editor of the Longford Leader, both of whom denied receiving such information.

PART TWO

THE GARDA INVESTIGATION

EYEWITNESS INFORMATION

- INTRODUCTION

- THE BOMB CAR

- OTHER SUSPICIOUS VEHICLES

- IDENTIFICATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

INTRODUCTION:

As one would expect, the Garda investigation team devoted a considerable portion of time and energy to collecting information from eyewitnesses who might have seen something suspicious.

Two albums containing photographs of UVF / UDA personnel and extreme loyalists from the Portadown area were compiled by Gardaí and shown to selected witnesses. According to the Investigation Report, no photographs were available of extreme loyalists from the Belfast area.

The photograph albums have not been found and it is not certain how many photographs they contained, though one of the Garda officers who showed the albums to witnesses indicated that they contained 23 and 31 photographs respectively.13 The Inquiry has not been given a list of names of those included in the albums. However, it has received copies of some spare photographs. Each photograph contains the name of the person concerned and is numbered to correspond with its position in the albums. The numbers received by the Inquiry were 1, 5, 22, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, 30 and

31. Two of these photographs were picked out by witnesses. Those who were not identified by witnesses included three persons who have been mentioned in intelligence information as possible suspects for the bombings: Stewart Young, and two men from Portadown, hereinafter referred to as Suspect T and Suspect D.

The investigation team amassed a considerable number of statements from witnesses who claimed to have seen something of possible relevance to the bombings. To include all of these sightings in this Report would only serve to confuse. With that in mind, the Inquiry has chosen only those sightings that were considered of particular significance by Gardaí at the time, or which seem to the Inquiry to be of potential significance. This is not to say that all or any of these sightings can be unequivocally accepted: eyewitness evidence is notoriously unreliable at the best of times, and the general quality of the identifications made in connection with the Dundalk bombing was poor.

The Inquiry’s final assessment of the value of the identification evidence obtained can be found in chapter 12 of this Report.

THE BOMB CAR:

The theft:

The car used in the attack on Kay’s Tavern was a red Mark II Cortina. It had been reported stolen from a street in the Shankill Road area of Belfast at 9.15 a.m. on the morning of 19 December. Gardaí reported the owner as saying that it had the words ‘FORD CORTINA’ on top of the windscreen in large white letters on a green background. The front mudguard was blue. It had no exhaust, and no first gear.14

The identity of the car was confirmed from the chassis number, 93KL 15246. The registration number of the car was AOI 9510, but it seems that false number plates were fitted after the car was stolen: Gardaí examining the wreckage found a number plate bearing particulars 3571 ZC with indications that it had been fitted to the bomb car. Enquiries revealed that this number was allocated to a Bedford bus owned by a man in Tullamore, Co. Offaly. Having interviewed the man and inspected his vehicle, Gardaí were satisfied that he had no connection with the attack on Kay’s Tavern.

Further examination of the 3571 ZC number plate established that it was not made in the State, as the figures on the plate were 3/8 of an inch smaller than those made in Dublin. An internal Garda memo listed two plate-making firms in Northern Ireland. There is nothing on the face of the document to indicate whether further inquiries were carried out, and with what result.

At a later stage in the investigation, D/Insp John Courtney and D/Sgt Owen Corrigan arranged a meeting in Belfast with a senior CID officer to discuss the theft of the bomb car. Specifically, they had been told that an RUC constable possessed information concerning the persons who had stolen the car. The senior officer identified the constable and accompanied them to Crumlin Road Station, Belfast to interview him.

“We spoke to a Detective Inspector there. I requested to see the Constable with the information. He said he was a D/Constable, that he would ring him and get him to come in and that he would give me every facility. At that stage [the senior RUC officer] said ‘I will not allow you interview that Detective Constable.’ I said that all I wanted to find out was the fact about the car, but he would not agree to me seeing him. D/Sergeant Corrigan and I left without seeing this D/Constable and returned to Dundalk.”15

The above passage comes from a statement made by John Courtney to Garda officers in April 2001. There is no mention of this incident in the contemporary documents seen by the Inquiry.

The route to Dundalk:

There were no definite sightings of the bomb car en route to Dundalk. A bus driver remembered passing two cars parked on the left hand side of the road near “the Stonetrough”, a crossroads about two miles out from Dundalk, on the Carrickmacross road. The cars were facing towards Dundalk town. This was between 4.05 and 4.10 p.m. He stated:

“All I can remember about the cars is that one was an old red one. It was the one nearest Dundalk and parked behind it was a large yellow car. I have no further description of the cars whatever… I cannot say if there were any persons in these cars.”16

As will be seen in the chapter on intelligence information, the RUC obtained confidential information suggesting that a red Cortina had been seen leaving Portadown on the morning of the bombing, in convoy with a silver Capri and another car (not described).17 No details concerning the model, registration number or general condition of the Cortina were supplied.

Sightings in Dundalk:

At around 4.40 p.m. a lorry driver was circling the block encompassing Crowe St, Francis St and Park St while waiting to collect a colleague. On entering Crowe St, the car in front of him stopped outside Kay’s Tavern:

“I was unable to overtake and flashed my lights. The driver of this car looked over his shoulder and then drove on and around into Francis St… Having gone around into Francis St this car was still in front of me. We both got out in Park St about the same time and just slightly above the Imperial I got held up by a lorry unloading beer. The car was able to pass on the left of this lorry. I got held up for a little while and after a bit of manoeuvring I managed to get by. I went around by the Demesne, into the Square and drove down into Crowe St. Arriving at Kay’s Tavern this car was again stopped just outside and double parked… I passed by on the left and circled into Francis St where I met my helper. We then went up Park St into the Dublin Road and down the Long Ave to Gaskins in the Industrial Estate. I arrived at Gaskins around 5.10 to 5.15 p.m.”18

He described that car as “… reddish in colour, not bright red or maroon, somewhere in between.” 19 However, he was certain that it was a “new-type” Cortina – that is, a Mark III, rather than a Mark II model. He also thought that the registration contained the numbers 6, 1, 3 and the letter I.

In a further statement made ten days later, the witness told Gardaí that he was “almost sure” he saw the driver again on 23 December 1975, near Dowdallshill on the Newry Road, Dundalk. This man went into a shop, then came out and drove away towards the Border in a grey Super Hillman Minx with British number plates. He again had three male passengers with him, but the witness was unable to say if they were the same as those he saw on the day of the bombing.20

When shown the photograph albums, the witness picked out two photographs of Samuel Whitten, a well-known UVF member from Portadown, as being like the driver of the car he saw.

A witness who entered Kay’s Tavern at 4.45 p.m. noticed a man trying to park a car directly outside the pub. When the witness came out again a minute or so later, he saw the same man getting into a maroon Hillman Hunter which was double-parked between Kay’s and Tempest Press. He said the registration number ended in BZ. There was another passenger in the front seat. The witness could not remember anything about the first car he saw, other than that it was a dark colour.

He picked out a photograph of a UVF member from Tandragee (referred to hereinafter as Suspect G), stating:

“He is very like the man who drove the car in at Kay’s Tavern and who got into the maroon Hillman Hunter, only he had no moustache and his hair was better groomed.”

Another witness who crossed the road to Kay’s Tavern from the Town Hall at 5 p.m. recalled seeing a “dull red or maroon” car parked outside Kay’s. It was facing towards Market Square, implying that it had come up Crowe St the wrong way, against the flow of traffic. As we have seen, the evidence suggests that the bomb car was facing towards Roden Place when it exploded.

The next sighting of a car that may have been the bomb car was at about 5.43 p.m. by a witness who said they saw a man standing on the footpath outside Kay’s Tavern, beside the driver’s door of a dark red Cortina:

“Now it appeared to me that this man was just after getting out of this car. I noticed he looked up towards the Square and as he did he pulled up the collar of his overcoat around his neck… After walking [a] couple of steps he started to run towards Francis St. In front of the Income Tax office he took his hand away from his coat collar and started to run faster. He ran up Francis St and I lost sight of him when he passed the low wall.”21

However, when asked to describe the car, the witness said that there was “a huge big spotlight right in the centre of the front grill” – something that no other witness mentioned, and that the bomb car did not have when it was stolen. Further doubt was cast on his evidence in the Investigation Report, which stated:

“Members who know this witness believe that he is unreliable.”

At approximately 6.05 p.m. two witnesses who were collecting for charity saw a dull red car stopped at traffic lights in Market Square. One of the collectors approached the vehicle:

“I spoke to the passenger who at first appeared to be reluctant to roll down the window. After consulting with the driver he did roll down the window and I produced the collection box to him. He asked me whom the collection was for and I explained to him. He then spoke to the driver and between them they agreed to put some money into the box. He then put his hand in his pocket and gave 10p which he put into the box himself. I offered him a badge which he refused. The driver then said ‘I will take it.’ I handed the badge to the driver. He put the badge on the dash of the car. The driver appeared not to want to get involved in a conversation, and when they got the badge the passenger immediately rolled up the window. I noticed that as they drove off they indicated their intention of turning left into Crowe Street. I do not know for sure if in fact the car did turn into Crowe Street, but I have a strong feeling that it did.

I would describe the car as a dull red colour. I have no idea of the make of the car but it had a sloping back. It could be a Cortina. I would describe the passenger as being about 25-27 years of age; medium build; hardy appearance, dark brown hair; ragged cut, straight and fairly long. It appeared to be thick. He appeared to be in need of a shave. He appeared to be small, as the driver seemed to sit higher than him in the car. He spoke with a soft Northern accent, wore a black polo neck shirt or jumper and a tweed jacket, bright colour. I cannot describe the driver too well, other than that he wore a leather jacket, blue colour. He was older than the passenger and taller; also he was better dressed. I cannot remember anything else about either man, or the car.”22

The other witness, who did not approach the car, also said that it contained two men. She described the passenger as follows:

“I would take him to be 25/28 yrs. His hair was dark, collar length and unkempt. He seemed to be wearing some type of bulky jacket, light coloured and tweed material. I would say he was not tall from looking at him sitting in the car. I could not give any description of the driver. The car was a dull red colour. I now know that it was a Cortina, because I saw one like it on Sunday 21-12-75… I asked a passerby what type of car it was and he told me it was a Cortina.”23

From the fact that the car was in the inside lane, she assumed that it turned into Crowe Street when the lights changed, though she did not see it doing so.

When shown the photograph albums on 4 January 1976, the witness who had approached the car failed to identify anyone. However, on 9 January she returned to Dundalk Garda Station and asked to be shown photographs again. D/Garda Terry Hynes reported:

“…at her request I produced to her an album of photographs (album no.1). After looking at the photographs [she] pointed to photograph no.6 and said ‘That is very like him, but he had no moustache. I am almost sure that is the man who was sitting in the passenger seat of a red coloured car on the 19th December, 1975 at Market Square, Dundalk. I sold this man a flag.’”24

At 6.07 p.m. another witness left Reilly’s pub and returned to his car, a green Ford Capri:

“My car was parked outside Kay’s Tavern on the right hand side facing Roden Place. The front of my car was outside Tempest window and the rear of it would be around Kay’s window, the window that joins Tempest building. At the rear of my car there was a brown Cortina, new type, parked. I cannot describe this vehicle any better. I can’t say what was parked in front of me.”25

At around 6.10 p.m. a man was driving down Crowe Street towards Roden Place. He told Gardaí:

“As I came to the railings at the end of the taxi rank I remember seeing a car double parked on my right. I cannot say if there were any cars parked inside this car or not, but it was stopped or parked on the traffic lane, on my right. This parked car was a Mark II Cortina. I cannot recall the colour, but it wasn’t a bright colour like white or cream. It was a dark colour…

I cannot say whether there was anybody sitting in the parked car… I cannot say whether the engine of this parked car was running or not.”26

It is known that a silver-grey Peugeot 504, unconnected to the bombing, was double parked outside Charlton’s Turf Accountants at about 6.10 p.m. It seems likely that this was the car which was seen by the above witness.27

On 23 December 1975, Gardaí took a statement from a man who said he saw a red Cortina being parked in Crowe Street at 6.10 p.m. He also claimed to have recognised the driver – a Belfast man whom he knew only as ‘Alexander’. He explained:

“I was reared travelling from place to place. When I was 10 years of age I was in Belfast with my family. We were camped in a place called the ‘Boulevard’ which is near the Queen’s Bridge. I left Belfast with my family when I was 15 years of age… During our stay in Belfast a man used to visit our camp most evenings during that 5 years. This man was about 20 years of age when he first came to our camp… I knew that this man was an ‘Orange Man’ because I saw him carrying a ‘King Billy’ banner in parades every 12th July. He would never talk about his religion. I don’t know if he worked or not. I don’t know where he lived but I am of the opinion that he was not too far from where we were camped in the ‘Boulevard’. The only name I knew this man by is Alexander.”28

He next saw Alexander on 12 July 1971, once more carrying a banner in a parade near City Hall. He did not speak to him that day.

On the evening of the bombing, the witness was sitting on a seat in Market Square. He heard the chapel bell ring for 6 o’clock:

“The bell was gone about 10 minutes when I decided to go home. I walked down towards the Cathedral on the footpath on the Town Hall side of the street. There was not much traffic around at the time. I saw a car pulling in beside a public house opposite the Town Hall to the spot where I showed you yesterday. It was a car the same as car DAI.432 which is outside the Garda Station now. I knew that it was a Ford Cortina car. I can’t remember the colour of the car. I saw a man get out of this car, out the driver’s door, which was near the pub. I looked at this man and I recognised him as the man I knew well in Belfast as Alexander. He looked much older and stouter. I have no doubt but it was him. I stood to watch him. I was thinking about going over to talk to him but just then a sports car came from the direction of the Square and stopped right in the middle of the street opposite where Alexander was. There was a driver and passenger in the car. The passenger got out and the man I know as Alexander got into the back of the car. The car drove off fairly fast straight down towards the Military Barracks.

I started to walk towards home. I walked straight down as far as the turn for Castle Rd where I turned left. I heard an explosion. I thought it was a tank that had burst. I kept on going home.”29

Next morning, having learnt that a bomb had gone off at Kay’s Tavern, he began to wonder if Alexander was involved:

“Later in the day I walked up the street and I saw where the pub was blown up facing the Town Hall. I made my mind up that it could have been the car that Alexander left there. This man, Alexander is 5’11” or 6’ tall, he is fairly stout… he has fair hair parted on one side. I think it’s the left… He was dressed in a black or brown leather jacket. I think it was black with a belt. I noticed that he was wearing dark gloves. I noticed this as he crossed the street to get into the sports car. I would say he is 40 or 42 years now. When I was 15 he was well over 20 years. I did not notice his trousers or shoes. He has kinda bulgy eyes with wrinkles under them. He has a little dimple on the front of his chin. He speaks with a proper Belfast accent. He has a thick lip at the bottom with a big mouth… I would pick him out for you, provided he did not see me or that I would not have to go to Court. I am not able to describe the passenger or driver of the sports car. The sports car was either brown or maroon or red; it’s much the same colour as car WID.456 which is outside the Garda Station but it was different at the back. It was all the one colour as far as I can remember.”30

The car WID.456, which the witness picked out as resembling the sports car in which ‘Alexander’ left the scene was a red Opel Manta.31 No details are given of car DAI.432, said by the witness to have been the same as the bomb car. It was presumably a Ford Cortina, though of what type is unknown.

The Detective Garda who took this man’s statement noted:

“Contact cannot read and could not take the number of the cars. Fairly reliable, has helped before.”32

However, the Investigation Report stated:

“It is advised that this witness’ statement should be treated with caution.”

The Report also stated that enquiries were being undertaken with the RUC to try and trace ‘Alexander’. No further references to this have been found in the documents available to the Inquiry. It seems the witness was not shown photographs of possible suspects.

The Inquiry has spoken to former Detective Sergeant Eoin Corrigan, who remembered this witness. He said the man did security work around the town, and as such might have been regarded as more reliable than the average witness. He could not explain the advice in the Investigation Report to treat his evidence with caution, but suggested that it may have stemmed from a perception that the witness was a ‘busybody’.

Also at about 6.10 p.m., an off-duty Garda officer parked his car outside Logan’s shop on Crowe Street, while his wife went inside. She returned to the car about two or three minutes later, and he started to pull out onto the road:

“As I pulled out I saw a car coming towards me from the opposite direction on its incorrect side of the road. The driver had failed to turn left at the traffic island at Roden Place, about ten yards to the front of where I had pulled out. Crowe Street and that portion of Roden Place where I was parked and in front of me, is a one-way street… I had to stop to avoid a collision with this car. While stopped I flashed my lights at the driver to indicate to him that he had taken a wrong turn. I thought he might go back as he could not get past me. He stopped but he made no attempt to go back. I pulled out to my right and passed him. As I was passing I saw him move ahead towards Crowe Street. I did not take any notice of this car after it had passed. I drove ahead to … Castle Road where we stopped to visit friends. Immediately we stopped the explosion went off and the lights in the town went out.

The car which I met at Roden Place… was a red coloured Cortina and it contained three male occupants, two in the front and one in the back. I would describe the driver as about 25 years with long black hair, a moustache and wearing dark glasses. He wore a dark coloured jacket. He looked to be of medium build, round face and about 5’8” or 9”. I cannot describe the two passengers other than to say that both had long hair and were of the same age group as the driver. I am unable to say anything about their dress. The car was a Mark 2 Cortina about five years old and in good condition. I did not get any view of the Registration number as the front of the car stopped too close to the left side of my car. It had dipped headlights and I did not notice anything peculiar about this car.”33

His wife also gave a statement on the incident. She described the car and its occupants as follows:

“It was a bright red coloured car, one of the older type Cortinas which seemed to be in good condition and well kept. I cannot give any assistance as to its reg no or as to any of the letters or figures in the registration. I cannot say whether it was a two-door or a four-door car.

The driver was about 25 yrs, with long black greasy unkempt hair and a small fringe in the front and parted on the left. He wore black rim glasses and a dark overcoat. He seemed to be a fellow of stocky build. I think I’d know him if I saw him again. He had two passengers, two men of about the same age group as himself, one in the front and one in the back. The front seat passenger turned his back towards us and I did not get a look at him. The back seat passenger kept looking out the side window on his right and kept his head turned away from me. The front seat passenger had long brown curly hair which was unkempt and the rear seat passenger had long dark hair.”34

On 5 January 1976, the albums were shown to the Garda officer and his wife. The Garda officer picked out two photographs of Samuel McCoo, a UVF member from Portadown. The officer who showed him the albums reported:

“Witness stated ‘This man resembles the driver of the car I saw if he had glasses.’ Identification not positive.”35

His wife, on the other hand, picked out two photographs of James Nelson Young as resembling the driver of the car. Again, her identification was marked “Not positive.”36

Another man and his wife were walking down Crowe Street towards Roden Place at about 6.15 p.m. According to the man, they had just passed Defender’s Row when they saw two men standing on the street beside a red car.

“It was a car similar to a new type Cortina. I have no idea of the Reg. No. of this car. They had a flash lamp in their hands. It appeared grey in colour. They appeared to be shining the light on the car. I just moved on a bit further down the street when I heard a bomb explode at Mulligan’s pub.

I would describe one of the men as 22 yrs., 5’6”, thin build, long face with very black hair. I do not know how he was dressed. He also wore a small moustache. I cannot describe the 2nd fellow other than he had dark hair. I think I would be able to recognise the 1st fellow again. I do not know where these two men went after the explosion. I also remember that the windows of the car were fogged up.”37

He picked out a photograph of Samuel McCoo as resembling one of two men he saw. Sgt Monaghan reported:

“Identification not positive and witness did not pick out any other photograph.”

The man’s wife, who was with him at the time but did not make a statement, picked out a photograph of James Nelson Young, saying “This looks like one of the men beside the car.”38 She too was not positive in her identification.

James Nelson Young was also said by another witness to bear “a fairly good resemblance” to a man he saw running along Crowe Street at about 6.15 p.m. on the night of the bombing. In his statement he described the encounter as follows:

“When I was passing the public toilets in Crowe St I saw a man cross the road from my left. He crossed the road diagonally about 10 yards in front of me… He was on the road when I first saw him. I would say that he had come from some position between Kay’s Tavern and Mark McLoughlin’s pub. He was running, but not wildly, as if somebody were after him. He was just running in a normal way as it were. He came onto the footpath at my side of the road and continued to run… I saw him stop just at the corner and look back down Crowe St… I lost sight of him then. I would say he turned right into Clanbrassil St.”

He described the man as:

“…about the same height as myself, 5’5”. He had black hair, greasy and straight and worn neck length… He had a black moustache. He appeared clean-shaven. He hadn’t a fat face. I am not a good judge of age but I would say he was aged 30 years at the most. He would definitely not be younger than 20 years.

He was wearing a beige polo-neck jumper and brown trousers… He was of medium build… He wasn’t wearing glasses and he hadn’t a limp. When he came onto the footpath he was about 10 yards in front of me.”

Also at around 6.15 p.m. another witness drove along Crowe Street with a friend. His intention had been to go for a drink in Kay’s Tavern:

“I was watching Kay Mulligan’s and I did not see any cars outside that I knew would belong to regulars in Kay’s. I remarked … that there would be very few in Kay’s at that time and we decided to go on to the Windmill Bar, Seatown Place. As I was looking at Kay’s going by it I saw a car parked properly by the kerb outside Kay’s bar door. I recall that there was at least one parking space in front of this car and maybe two parking places behind it… It was faced towards Roden Place.”39

He described the parked car as dark red or maroon, and said it appeared to be a Cortina or a Hillman Hunter. He could not give any more details. The car was empty when they passed it, and he saw no one else in Crowe St.

The two men drove on to the Windmill Bar at Seatown Place. They got parking straightaway and ordered two pints. As they were being poured, the bomb went off.

Further information as to the time at which the bomb car may have been parked outside Kay’s came from witnesses who were in Kay’s when the bomb went off.

Alice McErlean, a daughter of the owner, worked as a shop assistant. She finished work at 6 p.m. and arrived home at 6:10 p.m. She stated:

“A number of cars were parked immediately outside our premises, but I had no idea what type of vehicles these were. I went in through the bar... after one minute in the bar, I went upstairs to the living quarters... tea was ready... I had only started to eat at 6:20 pm, but there was a sudden flash and the lights failed.”

Another witness who seems to have entered the pub with a friend some time around 6.15 p.m. stated:

“When we were going into the pub, I saw two cars parked near it, I think one was a dark blue Renault, I don’t know the model, and I have no idea of the registration number. I don’t know which way it was facing, but it was directly outside of the pub, and on the St. Patrick’s side of a red Ford car. I don’t know what model it was either, or I don’t know the registration number. There were no people in these cars... Nobody came into the bar after me. I ordered two pints from John (the barman) and he had just started getting our drink when the bomb went off. I would say that we were in the pub about a minute and a half.”

This witness also gave details of two men who had about three months previously asked for directions to Kay’s: at the time, they were outside the next-door premises. They were seen at the door of the bar, but the witness did not see them enter. Another witness was approached by a man and a woman in Park Street and asked the way to Kay’s about a week before the bombing. From the description which was given of the man, he may have been one of the two men who had asked for Kay’s bar three months before. While the latter was shown photographs of suspects, the former was not. In any event, there was nothing to indicate that either pair was in any way involved in the bombing.

OTHER SUSPICIOUS VEHICLES:

Before the bombing;

Sometime between 4.10 and 4.20 p.m., four men were reported entering a bar approximately three miles outside Dundalk, on the Ardee-Dundalk road. They ordered drinks, followed by tea and sandwiches. They paid with two English five-pound notes.40 At one point, one of the men left the bar and went outside, where he watched passing cars. A witness stated:

“After a few minutes a car came travelling very fast from the direction of Dundalk. I do not believe there was anybody in the back and I am not sure if there was a passenger in the front… All I can say about it is that it wasn’t a very big car, it was fat and small and had two round headlamps on each side at the front. It looked to be newish. The colour was mustard… The man [outside the pub] nodded his head forward at the driver of the car as it sped past. His back was turned to me and he turned round immediately and I saw that he was smiling. He walked back to the front door and as he walked back he was still smiling.”41

It seems that the man then went back into the bar and called the others. Another witness, who had served the men their drinks, heard the front door of the bar opening and came out from the kitchen in time to see two of them leaving. The other two were already outside by that time. They had left two unfinished half-pints on the counter, and seemed to be in a hurry. The time was 4.40 p.m. The witness went outside and saw the men in a black car on the far side of the road, turning towards Ardee.

Both witnesses described the car in which the men arrived and left as a black Cortina. The second witness, who was suspicious of them, wrote down the registration number. Gardaí established that the number taken down by this witness was in fact allocated to a blue Corsair owned by a man from Andersonstown, Belfast. The RUC were asked to make further inquiries concerning this man, but existing Garda files show no record of any response having been received. In June 2001, this matter was taken up by An Garda Síochána with the RUC, at the request of the Inquiry. On 30 November 2001, the RUC replied, stating:

“No record of the motor vehicle or any investigation being carried out regarding the owner is held by Special Branch.”42

The witness who served drinks to the men gave the following descriptions of them to Gardaí: