Tithe an Oireachtais

An Comhchoiste um Chosaint Leanaí

Tuarascáil ar Chosaint Leanaí

Samhain 2006

Houses of the Oireachtas

Joint Committee on Child Protection

Report on Child Protection

November 2006

Table of Contents

Foreword of the Committee Chairman

Introduction

1. Establishment and Terms of Reference of the Committee

2. Committee Membership

3. The Work of the Committee

Substantive Criminal Law

4. Scope of the Prohibition on Sexual Acts with Children

- 4.2. Significance of the Decision in CC

- 4.3. The Effect of the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 2006

- 4.4. Analysis of the 2006 Act

- 4.5. The Context of Sexual Offences

- 4.6. The Scope of the Present Sexual Offences against Children

- 4.7. The Language of the Law

- 4.8. Summary of Recommendations relating to Offences

5. The Mental Standard of Guilt and the Available Defences

- 5.1. The Basis of Criminal Responsibility

- 5.2. Proof of Guilt of Unlawful Carnal Knowledge

- 5.3. The Decision in CC on the Constitutional Issue

- 5.4. The Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 2006 and the Issue of Mental Guilt 22

- 5.5. The Protection of Children and the Issue of Mental Guilt

- 5.6. Persons in Authority

6. Sentencing

- 6.1. The Position under the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1935 and the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 2006

- 6.2. "Penetrative Sexual Offences"

- 6.3. Age of the Victim and Sentence

- 6.4. First Offenders and Sentence

- 6.5. Persons in Authority and Sentence

- 6.6. Sentencing Policy/Guidelines

- 6.7. Mandatory Minimum Sentence

- 6.8. Discount for Plea of Guilty

The Age of Consent

7. What is the Appropriate Age?

- 7.1. Introduction

- 7.2. Age and Maturity in Irish Law

- 7.3. Proscription and Behaviour - the Impact of "Reality"

- 7.4. The Question of Capacity

- 7.5. The Value of Clarity

- 7.6. Different Ages, Different Standards

8. Provision for Young People

- 8.1. Protection and Inhibition

- 8.2. Criminality and Sentencing

- 8.3. Decriminalisation

- 8.4. Mitigating the Harshness of Criminality for Children

- 8.5. Gender Equality

Criminal Justice Procedures

9. The Special Position of Children

- 9.1. Introduction

- 9.2. The Special Needs of Children

- 9.3. Children as Vulnerable Witnesses

10. The Criminal Investigation

- 10.1. Statement of Complaint

- 10.2. The Garda Station

- 10.3. Recommendations of the Committee

- 10.4. Prosecution of Offences

11. The Criminal Trial Process

- 11.1. Introduction

- 11.2. Inquisitorial or Adversarial System

- 11.3. The Role of Cross-Examination

- 11.4. The Need for Protective Measures

- 11.5. The Position prior to the decision of the Supreme Court in CC

- 11.6. The effect of the decision in CC and of the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 2006

- 11.7. Existing Provisions in Irish Law

- 11.8. Comparative and Alternative Approaches

- 11.9. Measures relating to Cross-Examination

- 11.10. Other Practical Measures

The Implications of the Decision of the Supreme Court in CC and the question of Constitutional Amendment

12. The Decision of the Supreme Court in CC

- 12.1. The Effect of the Decision of the Supreme Court in CC

- 12.2. Implications of the Decision

13. The Constitutional Implications of Proposals for Reform

- 13.1. The Committee's Recommendations

14. The Welfare of the Child and the Criminal Justice System

- 14.1. The Rights of the Child and the Constitution of Ireland

Other Issues and Recommendations

15. Sex Offenders Registration and Supervision

- 15.1. The Sex Offenders "Register"

- 15.2. Access to the Information contained in the Sex Offenders "Register"

- 15.3. Vetting

- 15.4. Treatment of Sex Offenders

16. Education and Public Awareness

17. Table of Recommendations of the Committee

- 17.1. Substantive Criminal Law

- 17.2. The Age of Consent

- 17.3. Criminal Justice Procedures

- 17.4. The Implications of the Decision of the Supreme Court in CC and the Question of Constitutional Amendment

- 17.5. Other Issues and Recommendations

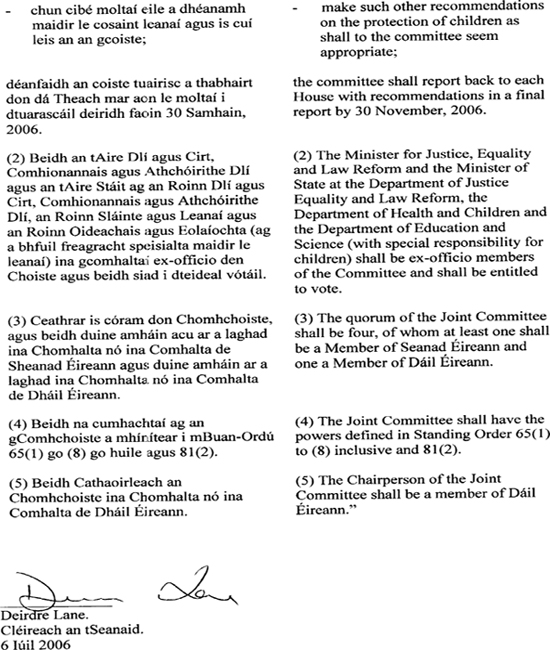

Appendix A. Orders of Reference of the Joint Committee

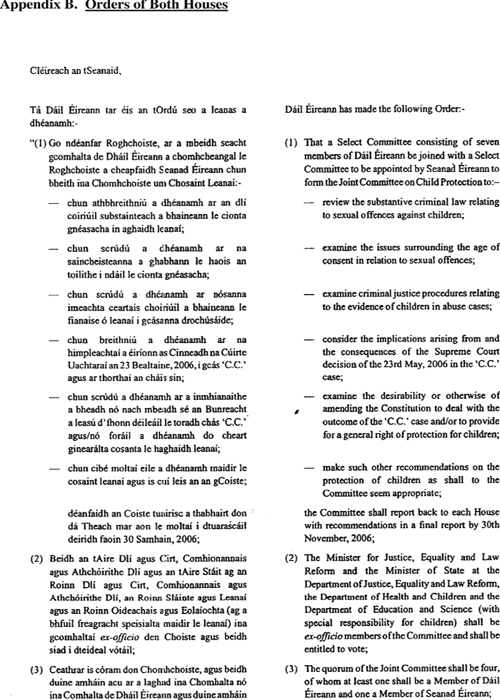

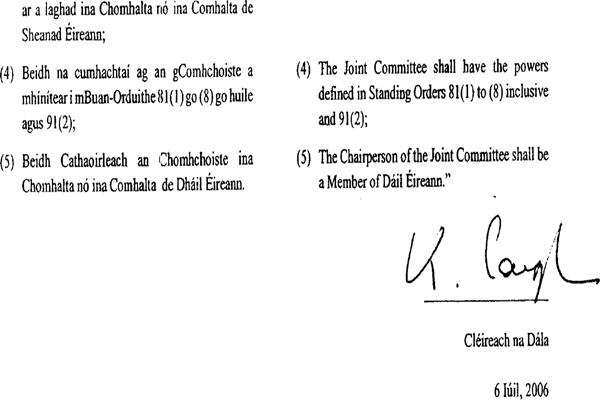

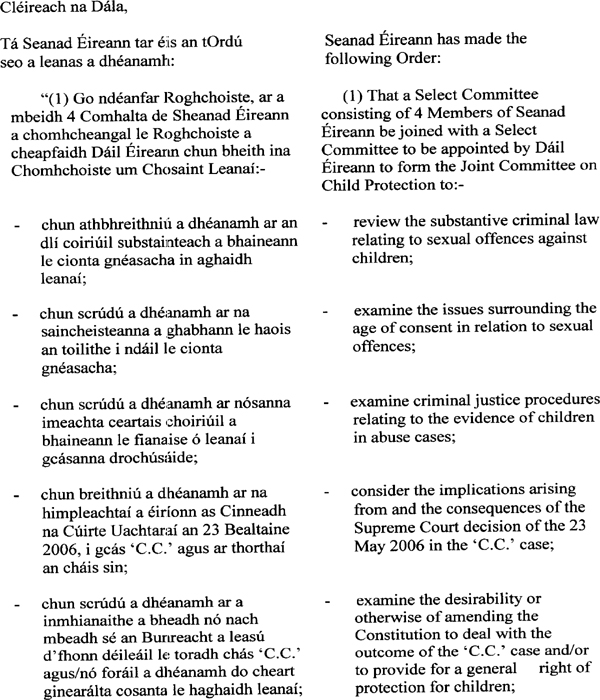

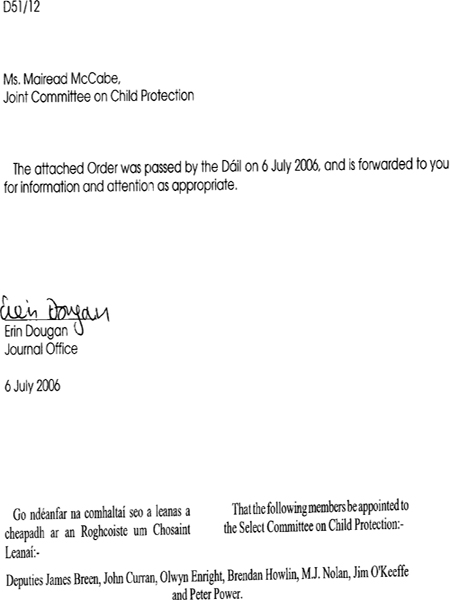

Appendix B. Orders of Both Houses

Appendix C. Submissions and Correspondence

- C.1. Submissions received by the Committee

- C.2. Correspondence received by the Committee

Appendix D. Meetings of the Joint Committee

Appendix E. Table of Legislation

An Comhchoiste um Chosaint Leanaí

Teach Laighean

Baile Átha Cliath |

|

Joint Committee on Child Protection

Leinster House Dublin 2 |

CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD

On behalf of the Joint Oireachtas Committee on Child Protection I am pleased to submit the report of the Committee to the Houses of the Oireachtas.

The issue of child protection is perhaps one of the most controversial and complex issues which the Oireachtas has had to deal with during the term of the 29th Dáil.

The decision of the Supreme Court in the “C.C.” case on the 23rdof May 2006, striking down a section of the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 1935, raised widespread serious concern in the country about the levels of protection being afforded to children in cases of “statutory rape” and sexual abuse.

Acting under considerable pressure of time and with the a real sense of urgency the Oireachtas enacted the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 2006. It must be said that the Oireachtas passed this legislation in the knowledge that the pressure of time might prevent an ideal solution from emerging. In these circumstances, the Oireachtas established the Joint Committee to examine all of the issues and to make recommendations.

The Committee has recommended that there should be an “absolute zone of protection” for children aged fifteen and under. The Committee has recommended that the defence of mistake as to age should not be available, in cases involving sexual activity, where a child victim is aged 15 and under. Furthermore, the Committee has recommended that there should be a Constitutional referendum empowering the Oireachtas to enact laws of absolute liability in relation to children.

The Committee has also made sixty two recommendations which it considers are necessary to ensure enhanced levels of protection to our children consistent with modern expectations in this area.

I would like to thank my fellow Committee members for their attention to detail and diligent work over the last number of months.

The complexity of this issue necessitated the retention of a specialist legal team consisting of Mr. Shane Murphy S.C. and Mr. Seán Guerin B.L. On behalf of the Committee, I wish to record our sincere thanks to our legal team for the enormous amount of time which they have committed to this project and to their expert advice at all times.

I wish to thank the Clerk of the Joint Committee, Ms. Mairead McCabe together with her colleagues, Áine Breathnach, Peter Malone and Colm Kennedy for their professionalism and diligence which has enabled the Joint Committee to publish its report within the timeframe laid down by the Houses of the Oireachtas.

I commend this report to the Houses of the Oireachtas.

PETER POWER, T.D.

November, 2006.

Part I

Introduction

1. Establishment and Terms of Reference of the Committee

1.1.1. On the 23rdMay 2006, the Supreme Court delivered its decision in CC v. Ireland, in which it found that section 1(1) of the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1935 was inconsistent with the Constitution. That section, and the related provisions of the Act, formed an essential part of the legal regime in this jurisdiction for the protection of children from sexual abuse. The immediate effect of the decision was to reveal a large gap in that regime, which urgently needed to be filled. Naturally, this was a source of immense public concern.

1.1.2. The immediate response of the Oireachtas was to enact the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 2006, which was enacted on the 2nd June 2006. That Act served two important purposes. First, it restored a regime of protection of children against sexual abuse and, secondly, it modernised and brought up to date the law in that area. That said, the law had been enacted as a matter of urgency and without any opportunity to engage in a process of consultation or period of reflection that would be normal in the case of such a significant legislative enactment. This Committee was established by resolutions of both Houses of the Oireachtas, on an all-party basis, to engage in such a process of consultation and to reflect on the issues involved.

1.1.3. The terms of reference of the Committee are to:

-review the substantive criminal law relating to sexual offences against children;

-examine the issues surrounding the age of consent in relation to sexual offences;

-examine criminal justice procedures relating to the evidence of children in abuse cases;

-consider the implications arising from and the consequences of the Supreme Court decision of the 23rdMay, 2006, in the ‘C.C.’ case;

-examine the desirability or otherwise of amending the Constitution to deal with the outcome of the ‘C.C.’ case and/or provide for a general right of protection for children;

-make such other recommendations on the protection of children as shall to the Committee seem appropriate;

and to report back to each House with recommendations in a final report by 30th November, 2006;

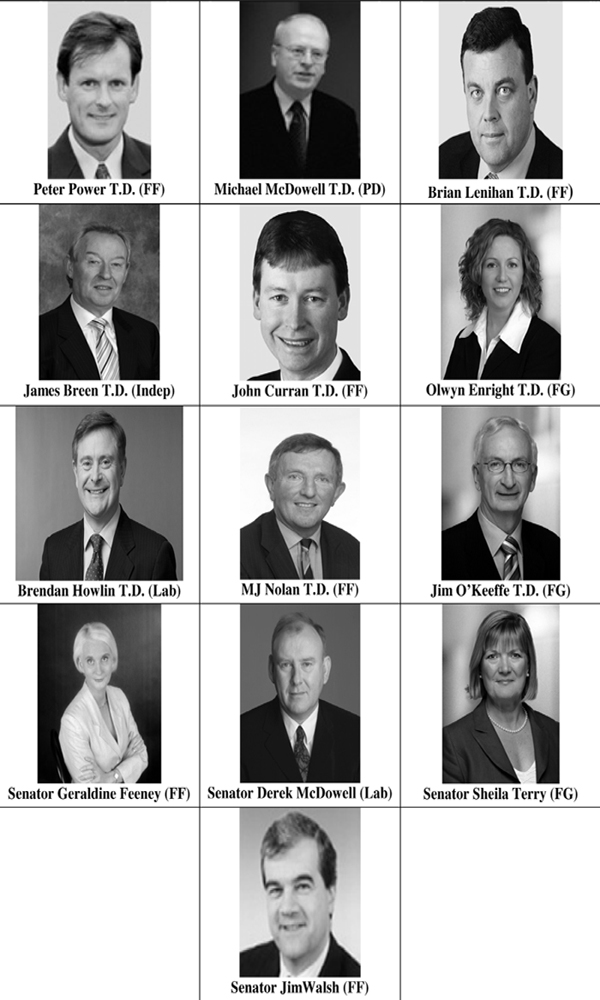

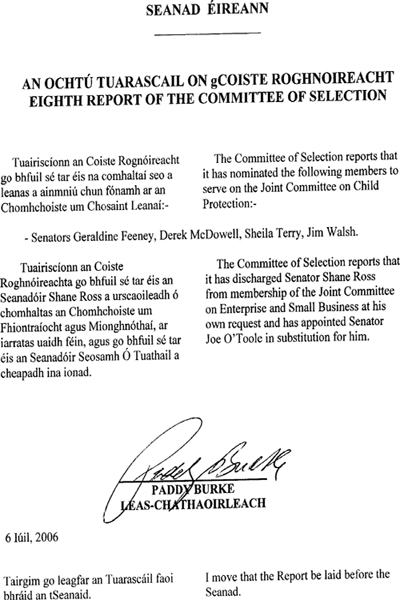

2.Committee Membership

3.The Work of the Committee

3.1.1. The work of the Committee has been focused from the outset on the issues that arose in CC and other issues concerning the provision made in the criminal law relating to sexual offences against children, as well as issues that arise in the context of the participation of child victims of sexual offences in the criminal justice system. Undoubtedly, this focus has been confined to only a part of the spectrum of issues of concern from a child protection perspective. However, given the importance and urgency of the issues entrusted to the consideration of the Committee, and the limited time available to the Committee to complete its work, such a focus was essential.

3.1.2. The Committee decided at the outset of its work to invite submissions from interested bodies and to advertise publicly for submissions. These invitations and advertisements resulted in the Committee receiving more than 50 detailed written submissions as well as a substantial volume of correspondence. The submissions and correspondence received by the Committee were of enormous assistance in its work. The range of views expressed in the submissions, on all of the issues examined by the Committee, have informed its recommendations. The Committee wishes to record its appreciation of the contribution made to its work by all of those who made submissions to or corresponded with the Committee.

3.1.3. The Committee was also pleased to receive a limited number of oral submissions from relevant experts in the areas of criminal law and child protection law, childrens’ rights, the operation of the criminal justice system, child and adolescent psychiatry, and forensic psychiatry. The occasion of these oral submissions also enabled the Committee to question the relevant experts on the issues arising in the course of the Committee’s work related to their respective areas of expertise. Again, the Committee wishes to record its appreciation of the contribution made by these experts to the work of the Committee.

3.1.4. There are five substantial parts to the report of the Committee. The first part examines the substantive criminal law relating to sexual offences against children, under three headings: the scope of the prohibition on sexual acts with children, the mental standard of guilt and the available defences, and sentencing. The second part of the Committee’s report examines the age of consent, with particular consideration given to fixing an appropriate age of consent, and to making provision for young people. The third part of the Committee’s report deals with criminal justice procedures. The report initially examines the special position of children and their needs within the criminal justice system, and goes on to examine the way in which those needs are met during the criminal investigation and during the criminal trial process. The fourth part of the report examines the implications of the decision of the Supreme Court in CC and the question of constitutional amendment. Finally, the report of the Committee examines issues related to sex offender registration, supervision and treatment, and to education and public awareness.

Part II

Substantive Criminal Law

4.Scope of the Prohibition on Sexual Acts with Children

4.1. Summary of Pre-existing Offences

4.1.1. It may be of assistance, at the outset of the Committee’s analysis of the scope of the prohibition on sexual acts with children, to examine the state of the law relating to sexual offences in general prior to the recent decisions of the Supreme Court. A brief summary of the principal relevant offences is set out below.

4.1.2. Rape is an offence contrary to common law and defined by statute, in particular the Criminal Law (Rape) Act, 1981. Section 2 of the Criminal Law (Rape) Act, 1981 states that a man commits rape if (a) he has sexual intercourse with a woman who at the time of intercourse does not consent to it, and if (b) at that time he knows that she does not consent to the intercourse or he is reckless as to whether she does or does not consent to it. Sexual intercourse is the penetration (however slight) of the vagina by the penis. Section 2(2) of the 1981 Act provides that if, at the trial for a rape offence, the Jury has to consider whether a man believed that a woman was consenting to sexual intercourse, the presence or absence of reasonable grounds for such a belief is a matter to which the Jury is to have regard, in conjunction with any other relevant matters in considering whether he so believed. The failure or omission by the victim to offer resistance to the act does not of itself constitute consent to the act.

4.1.3. Rape under Section 4 of the Criminal Law (Rape) (Amendment) Act, 1990 is defined as a sexual assault that includes (a) penetration (however slight) of the anus or mouth by the penis or (b) penetration (however slight) of the vagina by an object held or manipulated by another person.

4.1.4. Aggravated Sexual Assault, contrary to section 3 of the Criminal Law (Rape) (Amendment) Act, 1990 means a sexual assault that involves serious violence or the threat of serious violence, or is such as to cause injury, humiliation or degradation of a grave nature to the person assaulted.

4.1.5. Sexual Assault, encompasses the previous common law offences of indecent assault upon a male person and indecent assault upon a female person, as provided for by Section 2(1) of the Criminal Law (Rape) (Amendment) Act of 1990. Although the elements of the offence are not defined by statute, it consists of an assault accompanied by circumstances that are objectively indecent. Consent is not a defence to a charge of sexual assault if the victim is under the age of 15.

4.1.6. Buggery, since the enactment of section 3 of the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 1993, involves the commission or attempted commission ofan act of buggery (i.e. anal intercourse) with a person under the age of 17 years (other than a person to whom the accused is married or to whom he believes with reasonable cause he is married), a mentally impaired person, or an animal.

4.1.7. Gross Indecency, contrary to section 4 of the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 1993 prohibits acts falling short of buggery between a male person and another male person under the age of 17 years. (Provision is also made in respect of such acts committed with a mentally impaired male.)

4.1.8. Incest is committed where (a) a male person has sexual intercourse with a woman who is, and whom he knows to be, his mother, sister, daughter or granddaughter, or (b) a female person over the age of 17, with her consent, permits her father, grandfather, brother or son to have sexual intercourse with her.

4.1.9. Causing or Encouraging a Sexual Offence upon a Child, contrary to section 249 of the Children Act, 2001, is an offence committed by persons having care or control of children who cause or encourage unlawful sexual intercourse or buggery with the child under the age of 17, or who cause or encourage the seduction or prostitution of the child, or a sexual assault upon the child.

4.1.10. Unlawful Carnal Knowledge or Statutory Rape encompassed two different offences defined by reference to the age of the victim. Section 1(1) of the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1935 provided that the offence was committed by any person who unlawfully and carnally knows any girl under the age of 15 years. Section 2(1) of the same Act provided that the offence was committed by any person who unlawfully and carnally knows any girl of or over the age of 15 years and under the age of 17 years, although in this case the sentence was lower.

4.2. Significance of the Decision in CC

4.2.1. The underlying principle of primary importance re-established by the recent decisions of the Supreme Court in CC and PG is that a guilty mind is a necessary element of any criminal offence. This is particularly so in cases where the offence concerned is considered a true criminal offence, i.e. one where the behaviour concerned may be considered morally wrong to a high degree and where conviction leads to significant social stigma. This principle has a constitutional status so that, where the Oireachtas had intended that there be no requirement to prove a guilty mind in the case of such an offence, such a law would be constitutionally vulnerable.

4.2.2. This also means that, even where the law provides that a person below a certain age is not capable of consenting to certain activities, it is for the prosecution to prove the mental element, i.e. knowledge of age. If an accused raises a defence of mistake as to age, it is for the prosecution to prove that he knew better. This, of course, does not remove the concept of an age of consent; instead it re-affirms that if age is one of the externalelements of a crime, the corresponding internal or mental element must also be present.

4.2.3. Section 1(1) of the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 1935, which prohibited unlawful carnal knowledge of a girl under the age of fifteen, was declared to be inconsistent with the Constitution because it purported to permit conviction for a serious criminal offence without proof of mental or moral guilt. Although section 2(1) of that Act was not expressly considered by the Court, the conclusion that it too is inconsistent with the Constitution necessarily follows from the reasoning of the Supreme Court.

4.2.4. The common law offence of sexual assault remains a part of the law and, on a charge for such an offence in respect of a person under the age of fifteen, it is not necessary for the prosecution to prove that the young person did not consent. In such a case, however, where the accused says that he did not know that the victim was under fifteen, it is for the prosecution to prove that he did.

4.3. The Effect of the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 2006

4.3.1. The Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 2006 was enacted by the Oireachtas on the 2nd June 2006, ten days after the decision of the Supreme Court declaring section 1(1) of the 1935 Act inconsistent with the Constitution. As such, the Act must be seen as a timely response to a pressing and urgent need for legislation. During the course of the Dáil and Seanad debates on the Bill, certain aspects of the Bill which required further consideration or possible amendment were identified. The Committee was established, in part, for the purpose of examining these issues.

4.3.2. Introducing the Bill at the Second Stage in the Dáil, the Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform, Deputy Michael McDowell, said that it was

“designed to restore in updated form the offence of unlawful carnal knowledge against a girl of 15 years or under, which was struck down by the Supreme Court. The new offences contained in the Bill protecting children against sexual abuse contain a defence of honest belief that the child had obtained 15 or 17 years as appropriate in accordance with the Supreme Court judgment.”1

4.3.3. The Act repeals sections 1(2) and 2 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1935, as well as sections 3 and 4 of the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 1993. It prohibits any “sexual act” (i.e. sexual intercourse, buggery between persons who are not married to each other, an act described in section 4 of the Criminal Law (Rape) (Amendment) Act, 1990, or an aggravated sexual assault) and any attempt to engage in a “sexual act” with a child under the age of 17 years. If the child is under 15 years the offence ispunishable by life imprisonment. If the child is 15 or 16 years of age, the offence is punishable by 5 years imprisonment or two years in the case of an attempt, but in either case the penalty increases (to 10 years and 4 years respectively) if the offender is a person in authority. Similarly, the penalties are increased for a second or subsequent conviction. In no case will consent be a defence.

4.3.4. However, it will be a defence for the accused to prove that he or she honestly believed that the child had attained the relevant age and, in considering whether the accused had that honest belief, the court shall have regard to the presence or absence of reasonable grounds for so believing and all other relevant circumstances. In this way, the 2006 Act directly addresses the issue of concern to the Supreme Court in the CC case.

4.3.5. The Act effects a significant modernisation of the law, in that sections 1 and 2 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1935 prohibited only sexual intercourse with a girl. The 2006 Act extends the prohibition to other forms of sexual activity, whether with a male or a female child. In general, the 2006 Act is gender-neutral in its terms. The principal exception is that section 5 provides that a female child under the age of 17 years shall not be guilty of an offence under the Act by reason only of her engaging in an act of sexual intercourse.

4.4. Analysis of the 2006 Act

4.4.1. The Committee in its deliberations, which have been guided by the extensive and numerous submissions received from members of the public and experts, has focused its analysis on three distinct areas. First, the Committee has considered the substantive sexual offences designed for the protection of children and, in this regard, has examined both the pre-existing law and the law as it now stands following the enactment of the 2006 Act. In this area of its analysis, the Committee has considered recommendations made over the years concerning the substantive criminal law in this area, innovations in other jurisdictions, and the particular issues arising in the context of the present legislative arrangements. The remainder of this chapter is devoted to this analysis.

4.4.2. Secondly, the Committee has considered in some detail the issues concerning the requirement for proof of a guilty mind and the defences that may be made available to a person charged with the sexual offence against a child. These issues, of course, are at the very centre of the decision of the Supreme Court in CC. Again, the Committee has looked at earlier recommendations in this area, and arrangements made in other jurisdictions. In its consideration of these issues, the Committee has been particularly concerned with an assessment of the existing constitutional limits to legislative action as well as international human rights norms. These issues are considered in the next chapter.

4.4.3. Thirdly, the Committee has considered the issues relating to the question of sentence for sexual offences against children. Again, in its deliberations the Committee has been guided by earlier examinations of the subject, by developments both here and in other jurisdictions in the law relating tosentencing generally, and by the extensive submissions the Committee has received on this subject. These issues are considered in chapter 6.

4.5. The Context of Sexual Offences

4.5.1. As can be seen from the brief summary of the existing sexual offences provided for in Irish law above, there is a range of such offences, involving acts and circumstances of different degrees of gravity. Some of these offences remained entirely Common Law offences, some are Common Law offences that have been defined or redefined by statute, and others are statutory offences that have been enacted at different times because of gaps or defects that have been perceived to exist in the law. Because of the progressive way in which the law has been developed in this area, and because of the variety of sources for that law, the area may generally be seen as lacking somewhat in coherence and consistency. Professor Finbarr McAuley, Jean Monnet Professor of European Criminal Justice at UCD, told the Committee of his experience of the law in this area as chairman of the Criminal Law Codification Advisory Committee in 2004 in the following terms.

“I remember investigating the state of the law on sexual offences and, without too much investigation, my fellow committee members and I discovered that there were no fewer than 12 substantial Acts affecting the issue in this jurisdiction --13 following the 2006 Act. Having examined the matter in the context of codification, I have no doubt that one of the measures needed is the consolidation of the legislation in question into a single Act, if only because in a democracy the issue of access to the law is fundamental, as the Committee will appreciate.”

The Committee accepts the force of this argument, which also featured in a number of written submissions made to the Committee, including those of the Dublin Rape Crisis Centre and Youth Work (National Youth Federation. The Committee considers that the law relating to sexual offences would benefit from a general review, with a view ultimately to codification of the law. Such a review should include an examination of certain issues that have arisen during the course of the Committee’s work, but which have a wider significance. For example, a number of submissions to the Committee have argued that the notion of “consent” should be defined by statute. Furthermore, Senator Geraldine Feeney has argued that the issues arising in relation to the protection of children from sexual abuse need to be considered also for the protection of vulnerable adults, including those who are mentally impaired. These are important issues that the Committee considers merit further analysis.

The Committee recommends that the law relating to sexual offences, against both adults and children, be reviewed, perhaps by the Law Reform Commission, and ultimately codified in a single statute.

4.6. The Scope of the Present Sexual Offences against Children

4.6.1. In general terms, the offences provided for in the 2006 Act prohibit what might be described as “penetrative sexual activity” with children. Such activity is, obviously, the most serious form of child sexual abuse and that of greatest concern to society and the Committee. Although an act that amounts to an aggravated sexual assault need not necessarily involve an act of penetration, such an act is rightly considered, by its nature, as amongst the most serious of offences against children. The Committee thinks it proper that such serious sexual acts should constitute an offence distinct from lesser forms of sexual assault, and should attract a higher penalty.

The Committee recommends that the distinction observed in the present law between penetrative sexual activity and aggravated sexual assault on the one hand and lesser forms of sexual assault on the other hand should be preserved.

4.6.2. That said, the question arises whether there are grounds for drawing a further distinction between different types of penetrative sexual activity. Until the enactment of the Criminal Law (Rape) (Amendment) Act, 1990, the only form of penetrative sexual activity prohibited by law, whether in the case of an adult or child, was penetration of the vagina by the penis. Section 4 of the 1990 Act extended the prohibition to the penetration of the other major bodily orifices, and also extended the prohibition to penetration by inanimate objects (subject to some qualification, as to which see further below).

4.6.3. The change in the law effected by the 1990 Act was certainly necessary, in particular so as to expressly prohibit “male rape” or “homosexual rape”. That need was met in the United Kingdom a short time later, but in a different way. The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 re-defined the offence of rape by extending the definition of sexual intercourse, so that it included both vaginal and anal intercourse. In that jurisdiction the Sexual Offences Act 2003 again re-defined the offence of rape, so that it includes the penetration of the vagina, anus or mouth of another person with the penis. On each occasion the extension of the definition effectively prohibited the penetration of another orifice. On each occasion, however, the means by which penetration was achieved was confined to penetration by the penis. This is not to say that penetration by other means is not an offence, only that it is a different offence2.

4.6.4. There are reasons why the distinction between penile penetration and other forms of penetration ought to be observed by the criminal law. Obviously, in the case of penile penetration of the vagina there is a risk of pregnancy. Apart from that, however, in every case of penile penetration there is the risk of transfer of bodily fluid, with the attendant risk of disease, and a degree of forced intimacy with the body of the attacker that may not be present in the case of penetration by an object. These are differences of quality and significance and it is the view of the Committee that consideration should begiven to recognising these differences in the terms of the offences prescribed by law. The Committee appreciates that this issue has implications beyond the field of offences against children and it may be that further and fuller consideration of the issue may lead to a different conclusion.

The Committee recommends that consideration be given to distinguishing between the offence of rape with the penis and rape by an object.

4.6.5. The Committee notes that one possible gap3 that may be considered to exist in the law as it currently stands relates to the definition of rape under section 4 of the Criminal Law (Rape) (Amendment) Act, 1990. While it is an offence of rape under that section to penetrate the vagina by an object, such penetration of the anus is not an offence. Only penile penetration of the anus is an offence. This issue was considered in the Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform Discussion Paper on the Law on Sexual Offences of May, 1998, which stated:

“In its 1988 Report on Rape, the Law Reform Commission recommended that the crime of rape should be defined by statute so as to include non-consensual sexual penetration of the major orifices of the body, i.e. the vagina, anus and mouth by the penis of another person or of a person’s vagina or anus by an inanimate object held or manipulated by any other person and in this form the crime should be capable of being committed against men and women.

While the 1990 Act followed to a large extent that recommendation by the creation of an offence of “rape under section 4” it did not include in the definition of the offence penetration of the anus by an object. In favour of amending the definition of rape under section 4 is the argument is that it is somewhat artificial to attempt to distinguish penetration of any of the body orifices because the attack on the dignity and bodily integrity of the victim, and his or her utter and complete humiliation, is the same in all cases of penetration. The reasons given at the time of the debates on the 1990 Act for not including the penetration of the anus by an object in the definition of the offences were --

- a grave sexual assault involving penetration of the anus by an object would come within the general meaning of an aggravated sexual assault,

- there are times when the penetration of the anus might not amount to an aggravated sexual assault, such as horseplay between schoolboys which results inpenetration of the anus by an object such as a pencil and it would be wrong to categorise such as rape.”4

4.6.6. Given the views expressed above concerning the desirability of giving special recognition in the law to the gravity of penetrative sexual offences, the Committee is inclined to favour the views originally expressed by the Law Reform Commission. In the view of the Committee, the inclusion in the offence of rape under section 4 of acts involving penetration of the anus by an object would make the offence more complete and more coherent. While such acts certainly amount also to a sexual assault or an aggravated sexual assault, this in itself is no reason to exclude such acts from the category of penetrative sexual assaults. The possibility of horseplay between boys accidentally resulting in such an act being committed is not, to the Committee’s mind, a reason to exclude what in other circumstances would be a very serious penetrative sexual assault from the definition of that type of offence.

The Committee recommends that the definition of the offence of rape under section 4 of the Criminal Law (Rape) (Amendment) Act, 1990 be extended to include penetration of the anus by an object.

4.6.7. In the Dáil debate on the 2006 Bill, Deputy Brendan Howlin drew attention5 to the fact that a sexual act, falling short of penetrative sex, committed by an adult male with the consenting 15-year-old boy amounted to an offence of gross indecency contrary to section 4 of the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 1993, but that the section is repealed by the 2006 Bill, without replacement. This defect in the law was also brought to the Committee’s attention in written submissions, including those of Young Fine Gael, One in Four, and the Director of Public Prosecutions, who described it as a “significant lacuna”.

4.6.8. The identification of this lacuna leads naturally to a consideration of the next most serious level, after penetrative activity, of sexual offending against children. The submissions received by the Committee recommend, in significant number, the enactment of an offence of child sexual abuse and a child endangerment offence. Other submissions, without being quite so specific, have suggested that the protection of children be extended to acts of exploitation and corruption. It has been submitted that the sexual acts prohibited should be defined by law.

4.6.9. Essentially, as the law currently stands, the appropriate offence to be charged in the case of non-penetrative sexual activity with children is sexual assault. This gives rise to two distinct difficulties. The first is that, as the law currently stands, consent is a defence to a charge of sexual assault of a person aged 15 or over. The Committee is concerned that this may notprovide the necessary level of protection to young people. (Issues related to consent are considered in more detail in Part III of the Committee’s report.) The second difficulty is that the necessity to prove the standard elements of the offence of assault, in particular the threat or application of force to another, may mean that certain forms of conduct or sexual activity with or in the presence of children that should be criminalised are not.

4.6.10. These difficulties were considered by the Law Reform Commission in its report on child sexual abuse.6 The solution recommended by the Law Reform Commission was that an offence of “ child sexual abuse” or “ sexual exploitation” should be enacted. Such an offence should, according to the Law Reform Commission be based on the Western Australian definition of child sexual abuse. That definition is as follows

- intentional touching of the body of a child for the purpose of the sexual arousal or sexual gratification of the child or the person;

- intentional masturbation in the presence of a child;

- intentional exposure of the sexual organs of a person or any other sexual act intentionally performed in the presence of a child for the purpose of sexual arousal or gratification of the older person or as an expression of aggression, threat or intimidation towards the child; and

- sexual exploitation, which includes permitting, encouraging or requiring a child to solicit for or to engage in prostitution or other sexual act as referred to above which the accused or any other person, persons, animal or thing or engaging in the recording (on video-tape, film, audio-tape, or other temporary or permanent material), posing, modelling or performing of any act involving the exhibition of a child’s body for the purpose of sexual gratification of an audience or for the purpose of any other sexual act referred to in subparagraphs (i) to (iii) above.7

4.6.11. The Committee recognises that there is some overlap between an offence of child sexual abuse, based on the Western Australian definition, and the proposed offence of sexual grooming contained in Head 8 of the Heads of Bill for a Criminal Law (Trafficking in Persons and Sexual Offences) Bill, 2006. Each of the proposed offences, however, lacks something which the other would bring. For example, an offence is committed under the Western Australian definition where a sexual act is intentionally performed in the presence of a child for the purpose of sexual arousal. The 2006 Heads of Bill, however, provide that an offence would be committed where the act is done, not only in the presence of a child, but in a place from which the person can be observed by a child. Further provision is made in the same Head of Bill, prohibiting even the preparatory step of arranging to meet a child for the purpose of a sexual offence.

4.6.12. In order to develop a coherent scheme of offences of child sexual abuse, the Committee is inclined to the view that the next most serious offence, after the offence of defilement (i.e. principally penetrative sexual abuse), should be a general offence of child sexual abuse, along the lines recommended by the Law Reform Commission, supplemented by the somewhat broader definition of the offence contained in the 2006 Heads of Bill. The defining element of this offence of child sexual abuse would be that some sexual act, behaviour or contact occurs, which falls short of penetration.

The Committee recommends the enactment, as a legislative priority, of an offence of child sexual abuse, as recommended by the Law Reform Commission, and including in addition other forms of sexual act, contact or behaviour falling short of penetrative sexual activity.

4.6.13. The Committee recognises that the scheme which it has recommended for offences of sexual abuse against children, i.e. an offence of child rape by penile penetration, an offence of child rape by other penetrative or very degrading or humiliating sexual activity, and an offence of child sexual abuse for other forms of sexual act, contact or behaviour, would still fail to criminalise lower forms of grooming or preparatory acts, designed to facilitate child sexual abuse, of whatever form, at some time in the future. Such acts should also be criminalised and an offence of grooming a child for sexual abuse, in that sense, would form the fourth and lowest tier of child sexual abuse offences.

The Committee recommends the enactment of an offence of grooming a child for sexual abuse, prohibiting acts preparatory to, or for the purpose of facilitating, the sexual abuse of a child at some time in the future, or placing a child in danger of being so abused.

4.6.14. The recommendations the Committee has made in respect of offences prohibiting the various forms of child sexual abuse are designed to deal with the situation where an individual is involved personally, whether as principal or accessory, in the abuse of one or more individual children. The Committee recognises, however, the need to enact additional offences related to the trafficking, sale or organisation of children for the purpose of sexual abuse in any part of the world, as envisaged in the Heads of Bill for a Criminal Law (Trafficking in Persons and Sexual Offences) Bill, 2006.

The Committee recommends the enactment of legislation providing for additional offences related to the trafficking, sale or organisation of children for the purpose of sexual abuse in any part of the world.

4.7. The Language of the Law

4.7.1. The terminology employed in legislation or in discussion of the law has featured in a number of submissions to the Committee. According to the Irish Association for the Study of Delinquency, the phrase “statutory rape” is

“outmoded, irrelevant and unhelpful…. Where there is no consent to a sexual act, irrespective of the ages of the parties it is rape.”

4.7.2. A similar view was expressed, although in support of a slightly different submission, by One in Four, who said

“Put simply rape is rape; the same charge should be applied regardless of the gender of the victim. We are acutely aware that many male victims of sexual abuse feel that the application of charges of gross indecency or buggery rather than oral or anal rape somehow imply consent on their behalf and are seen as a lesser crime.”

4.7.3. It was also submitted to the Committee that “defilement” is an inappropriate term, which adversely reflects on the victim. According to the Dublin Rape Crisis Centre, the term “ defilement”

[i]s an archaic term, with psychological, emotional and moral implications, [and should] be replaced with the term ‘sexual abuse’ or ‘sexual assault’”.

4.7.4. While the Committee are sympathetic to the view that the statutory label for a particular offence should not in any way reflect adversely on the victim of that offence, equally the Committee is of the view that it is important for the nature and gravity of the offence to be clear from the label applied to it. For that reason, the Committee would distinguish between the offence of child sexual abuse, as suggested in its recommendation above, and the more serious forms of penetrative sexual abuse. The Committee is open to the idea that there may be a way of describing the latter which is preferable to “defilement”, but it has not received any submissions identifying such a phrase or label. The Committee does not agree that the label “rape” simpliciter should be applied in all cases of penetrative sexual abuse. The Committee considers it desirable to distinguish the gravity of an offence of rape against a child. It may be that “child rape” would be a suitable label.

The Committee recommends that consideration be given to renaming the offence of “defilement” as “child rape” so as to recognise the sensitivities of victims of that offence, but not in any way that would disguise the gravity of an offence of penetrative sexual abuse of a child.

4.8. Summary of Recommendations relating to Offences

4.8.1. It may be of assistance, at the conclusion of this chapter, to summarise briefly the recommendations that the Committee has made in relation to a proposed scheme of offences covering various forms of child sexual abuse. The Committee has proposed, essentially, that the law provide for four different types of offence, as follows:

- The most serious is child rape by penile penetration.

- The next most serious is other forms of child rape, i.e. penetrative sexual activity or other very degrading or humiliating sexual activity.

- The third offence is child sexual abuse, which would, in essence, cover other situations where a sexual act is performed on or with a child or in the presence or view of a child.

- Finally, the offence of grooming a child for sexual abuse would cover acts preparatory to or intended to facilitate the sexual abuse of a child at a later date and would include, for example, arranging to meet a child for that purpose, or showing pornographic material to a child.

5.The Mental Standard of Guilt and the Available Defences

5.1. The Basis of Criminal Responsibility

5.1.1. Criminal liability, i.e. the liability of the citizen (or any person) to punishment at the hands of the State for a wrong considered criminal, depends upon the presence of two essential elements, one external and one internal. The external element is the proscribed conduct and is known as the actus reus; the internal element is the state of mind of the accused and is known as the mens rea. The concept of the actus reus is not limited, as the name may appear to suggest, to the doing of prohibited acts. It may also apply to prohibited omissions, e.g. the failure of an employer to provide and maintain a safe place of work. Equally, it must be borne in mind that an act or omission in itself may not be sufficient to establish the actus reus. Criminal liability may depend on the circumstances in which that act or omission occurs. It is for the law (either the common law, where that continues to apply, or the Oireachtas, by way of legislation) to specify with clarity what acts or omissions are prohibited, and in what circumstances. Criminal liability depends on proof of all the factual elements of the offence, i.e. both the prohibited act or omission, and the specified attendant circumstances. But that alone is not sufficient.

5.1.2. It has long been established that “an act does not make a man guilty of a crime, unless his mind be also guilty”. The mens rea is the guilty mind. This principle, long-established, is of obvious merit, given the severity with which the State can punish criminal wrongs. The same act may be done by two different individuals, only their intention differs, but that difference is sufficient to distinguish criminal from non-criminal behaviour.

5.1.3. The law recognises different degrees of guilt in the mind and sets the standard for criminal liability at different levels in different cases. The highest standard of mental guilt is intention, i.e. that the accused acted (or omitted to act) for the purpose of causing the harm prohibited by law or acted to achieve a different purpose knowing that the prohibited harm was a virtually certain consequence. The crime of murder is not committed every time a person is killed, but only if the killer intended to kill or cause serious injury to the victim. Such intent involves mental guilt of a high degree. In law, a person is presumed to intend the natural and probable consequences of his/her acts.

5.1.4. Closely related to the concept of intention is knowledge. Indeed, intention may be thought of as knowledge of the consequences of one’s act or omission. Knowledge plays an important role in criminal liability because such liability may depend, not merely on the commission of some act or on an omission, but also on the circumstances in which that occurs. For example, it is no offence to allow another person to use one’s property, but it becomes an offence if one knows that the property is being used for the manufacture of a controlled drug. Knowledge that those circumstances are present again involves a high degree of mental guilt.

5.1.5. Recklessness is a lower standard of mental guilt and may be applied both to the attendant circumstances of an act or omission and to its consequences. Recklessness involves conscious disregard of a substantial and unjustifiable risk of the material element of the offence existing or resulting, and it involves culpability of a high degree (although not as high as in the case of intention). In other words, although the accused may not have intended the particular harm prohibited by law, he or she has considered the possibility of such harm occurring, but has chosen to act regardless, and run the risk that it will occur. Or alternatively, although the accused does not know that a circumstance exists that would render an act unlawful, he or she has considered the possibility that it does and chosen to act regardless. In Irish law, the question of recklessness focuses on the mind of the individual accused, not on what might be thought objectively to be obvious risks.

5.1.6. The focus on the mind of the individual accused is unnecessary if the standard of mental guilt is set lower, at the level of criminal negligence. Criminal negligence may be said to occur if no normal person would ever be unaware of the danger created. At present, in Irish law, this standard applies only to the offence of manslaughter. As such, it applies only to negligence in respect of consequence (i.e. the death of a person) and not in respect of circumstances.

5.1.7. The ordinary standard of negligence also has some application to criminal law, but only generally in respect of minor offences, e.g. careless or dangerous driving (but including dangerous driving causing death). The ordinary standard of negligence is a failure to take reasonable care in the conduct of one’s affairs to avoid causing foreseeable harm to others. The standard of reasonableness is objective.

5.1.8. Absolute liability is imposed where the law provides that, upon proof of the external or factual elements of the offence, guilt itself is proved, without regard to any mental element. Strict liability similarly does not require proof of any mental element, although the possibility is left open that a defence can be raised by the accused. Offences involving either of these standards effectively forgo any requirement for mental guilt or mens rea. Such an approach has been considered appropriate to deal with regulatory offences (i.e. offences where the conduct is not of a truly criminal character, but has nonetheless been prohibited, usually because this has been considered necessary for the proper regulation of a particular activity or business) or offences contrary to the public welfare. This latter phrase may cause some confusion. Every crime is by definition contrary to the public welfare – that is why the State prosecutes wrongdoers even where the individual victim might also sue them. A public welfare crime is one where, quite apart from the general sense of public welfare, direct harm is done to a significant part of the population.

5.1.9. The main arguments in favour of strict or absolute liability are, first, that the protection of certain social interests requires a high standard of care and attention, which is likely to be promoted by the understanding that a mistake will not be a defence. Secondly, it is argued, that proof of mental guilt insuch cases may be impossibly burdensome on the prosecution, but that this is balanced by relatively low penalties and the absence of the high degree of shame and opprobrium that apply in the case of conviction for true crimes. On the other hand it is argued that such an approach is a departure from the fundamental principles of criminal liability, that the assumption of greater effectiveness has no empirical foundation, that conviction without mental guilt can bring the law into disrepute, that real stigma may nonetheless apply, and that the administrative argument has little weight.

5.1.10. It is, of course, open to an accused person to contest the presence of the necessary external and internal (or mental) elements of a crime with which he is charged. In any event, there is usually an obligation on the prosecution to prove each of these elements beyond reasonable doubt. If it fails to do so, the accused will be acquitted. But even where it appears that the prosecution is in a position to prove all the necessary elements, one or more of the positive defences known to the law may be available to an accused. For example, where the offence involves the use of force on another person, it may be argued that the force was lawful, e.g. to protect the life or health of others. In a murder case, the accused may argue that he was so provoked by the deceased as to have lost his self-control. (This is only a partial defence – the accused will still be guilty of manslaughter.) The accused may admit that he committed the crime but say that he did so under threat of death from another, i.e. duress. Insanity may be pleaded as a defence (now governed by the Criminal Law (Insanity) Act 2006) or automatism, but these may properly be seen as defences based on the absence of the required mental standard. Intoxication is not a defence as such, but it may deprive the accused of the capacity to form the necessary mental element. Mistake may be a defence, but it is perhaps better seen as the absence of the necessary mental element. It should be noted, however, that a mistake may be genuine or honest, without there being reasonable grounds for it.

5.2. Proof of Guilt of Unlawful Carnal Knowledge

5.2.1. The offence of unlawful carnal knowledge, as enacted in sections 1 and 2 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1935, consisted of two external elements. The first was the act of sexual intercourse itself. The second was circumstantial, i.e. that the act of sexual intercourse had occurred with a girl below the relevant age. It had long been thought that, provided the prosecution could prove these two external elements, the offence itself would be proved, without any particular mental element having to be proved. This was the issue considered by the Supreme Court in its first decision in the CC case, delivered on the 12th July 2005. The Court concluded that the traditional understanding of what was required to be proved by the prosecution on a charge of unlawful carnal knowledge was correct, as a matter of interpretation of the legislation.

5.2.2. The accused had argued that the offence should be interpreted so as to allow for a defence of mistake as to age. Such a defence, it was argued, was always available to an accused, even where the statute did not expressly provide for it, because proof of mental guilt was a necessary element of anyserious criminal offence. A majority of the Court concluded, however, as a matter of interpretation of the 1935 Act and its legislative antecedents (in particular, the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1885), that the Oireachtas had clearly intended to exclude such a defence. It was this offence, then, so interpreted, that the Supreme Court subsequently declared to be inconsistent with the Constitution.

5.3. The Decision in CC on the Constitutional Issue

5.3.1. Having heard further argument in the CC case on the issue of the consistency of section 1(1) of the 1935 Act with the Constitution, the Supreme Court delivered its judgment on the 23rd May, 2006. There was a single judgment on behalf of the entire Court delivered by Hardiman J.

5.3.2. The Court noted that an offence such as this, to which there was no defence once the factual elements (actus reus) were established, was rare, even in the case of offences that society viewed as being very serious. Although it was argued that cases where there was no guilty mind (e.g. because of a genuine mistake as to age) could be accomodated when sentencing the accused, the Court did not accept this approach. A conviction for the offence, whatever sentence was imposed, would carry a social stigma, compounded by the requirement to register as a sex offender, which would bring intense shame on the individual and his family and would lead to his exclusion from certain professions.

5.3.3. The purpose served by such a strictly defined offence the Court presumed to be “the protection of young girls from engaging in consensual sexual intercourse”. This is, of course, a “legitimate end to be pursued by appropriate means”.

5.3.4. The Court noted that in other jurisdictions and in previous decisions of the Supreme Court (e.g. the reference of the Employment Equality Bill) some emphasis has been placed on “the central importance of a requirement for mental guilt before conviction of a serious criminal offence, and the central position of that value in a civilised system of justice”. Accordingly, the Court “cannot regard a provision which criminalises and exposes to a maximum sentence of life imprisonment a person without mental guilt as respecting the liberty or the dignity of the individual or as meeting the obligation imposed on the State by Article 40.3.1° of the Constitution”, which provides: “The State guarantees in its laws to respect, and, as far as practicable, by its laws to defend and vindicate the personal rights of the citizen”.

5.3.5. The alternative view, that such a provision is necessary to provide a deterrent to engaging in sexual intercourse with minors, was considered. The Court concluded that this end could be achieved by legitimate means, including those involving the use of the criminal law, without the manifest injustice of permitting conviction of a serious criminal offence without any requirement of mental or moral guilt.

5.3.6. The Court therefore declared section 1(1) of the 1935 Act to be inconsistent with the Constitution. It declined the invitation from counsel for the State to confine its declaration to saying that the section was inconsistent with the Constitution only to the extent that it precluded an accused from advancing a defence of reasonable mistake. In the Court’s view, that would have involved it in a process akin to legislation. The Court concluded that “more than one form of statutory rape provision … would pass constitutional muster, and it does not appear to be appropriate for the Court, as opposed to the legislature, to choose between them”.

5.4. The Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 2006 and the Issue of Mental Guilt

5.4.1. Sections 2 and 3 of the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 2006 prohibit engaging in, or attempting to engage in, a sexual act, as therein defined, with a person under the age of 15 years and 17 years respectively.

5.4.2. Section 2(3) of the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 2006 provides:

“It shall be a defence to proceedings for an offence under this section for the defendant to prove that he or she honestly believed that, at the time of the alleged commission of the offence, the child against whom the offence is alleged to have been committed had attained the age of 15 years.”

5.4.3. Section 2(4) of the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 2006 provides:

“Where, in proceedings for an offence under this section, it falls to the court to consider whether the defendant honestly believed that, at the time of the alleged commission of the offence, the child against whom the offence is alleged to have been committed had attained the age of 15 years, the court shall have regard to the presence or absence of reasonable grounds for the defendant’s so believing and all other relevant circumstances.”

5.4.4. A similar provision is made in section 3(5) and (6) in respect of offences committed with children under the age of 17 years. In form, therefore, the 2006 Act maintains the previous position that, in a prosecution for unlawful carnal knowledge or defilement, it is for the prosecution to prove that the prohibited sexual act (which, as stated above, is much more extensive a phrase than merely sexual intercourse) occurred and that the victim was under the relevant age. In principle, that is all that the prosecution is required to prove. The Act does, however, permit the accused to raise a defence of mistake as to age. Furthermore, it appears that it is for the accused, not only to raise the defence, but also to prove it.

5.4.5. In setting the standard of mental guilt of the accused, the Oireachtas has focused on the subjective belief of the accused as to the age of the victim. For the defence to succeed, the jury must be satisfied that the belief asserted was honestly held. Provided that the belief was honestly held, it need not bea reasonable one, although, in determining whether or not the belief was honestly held, the jury must have regard to the presence or absence of reasonable grounds for the belief and all other relevant circumstances.

5.5. The Protection of Children and the Issue of Mental Guilt

5.5.1. On the whole, the primary effect of the Supreme Court decision in CC, i.e. that there must be a defence of mistake as to age, is accepted in the submissions received, although not without qualification. The qualifications vary. Some submitted that the defence should not be available to persons in authority or in cases of a victim below a certain age – 13 or 14. There is significant support for the view that the question should be approached on an objective basis, such as the standard of reasonableness.

5.5.2. Whatever the qualification proposed to the principle that a defence of mistake should be available to a person accused of an offence involving sexual activity with a child, a common thread runs through them all. That is a clear and definite sense of dissatisfaction with the idea that the availability of such a defence will lead inevitably to the cross-examination of children as to how they behaved, dressed or otherwise comported themselves. That result is indeed unavoidable, if the defence is allowed, because the only possible basis for a mistake having been made as to the age of the child is the appearance and/or behaviour of the child. Furthermore, although the defence would be difficult to establish in the case of a person who knows or has responsibility for the child, the position will be quite different with strangers. As the Director of Public Prosecutions submitted,

“In the case of a stranger, or newly-met acquaintance, the defence is far more likely to be successful. A girl going out to a bar or disco, for example, will frequently dress so as to appear older than she is, particularly if she is hoping to buy or consume alcoholic drink, or be let into an establishment with a door policy on age.”

5.5.3. The Committee shares the dissatisfaction expressed in the submissions it has received with the effects of a defence of mistake as to age. Although the Committee has made recommendations elsewhere in this report designed to ease the hardship associated with the giving of evidence in criminal trials by children, it considers that no measure that might be introduced to that end could be a sufficient response to the unacceptable possibility of children being cross-examined as to their behaviour and appearance in the case of an alleged sexual offence.

5.5.4. It is the view of the Committee that the existence of such a defence – honest, reasonable or otherwise – amounts to a failure to meet the necessary standard of protection of children. In effect, that defence would allow an accused person to lay the blame for his or her actions at the door of the child victim. In those circumstances, the guilt of the accused is measured by the precocity of the child. Such an approach, in the opinion of the Committee, is erroneous.

5.5.5. Society is entitled to expect that individuals of whatever age should avoid engaging in any sexual activity that might involve a child. This expectation is matched by an individual moral obligation borne by all persons to ensure that their sexual partner is an adult. The discharge of that obligation requires a degree of caution in the conduct of sexual relations. It may sometimes mean that such relations must be forgone, if the individual concerned cannot be certain that his or her intended partner is an adult. The Committee considers that a person who proceeds to engage in sexual relations with a child, and therefore necessarily in the absence of certainty that their intended partner is an adult, voluntarily assumes the risk that their behaviour will harm a child. Such behaviour is not free of moral guilt, and it merits the sanction of the criminal law. The Committee considers that the law must make clear to everyone who assumes the risk of harming a child by their sexual activities, that that risk is matched by the hazard of an appropriate sentence, accompanied by appropriate measures designed to protect society from sex offenders. This, in the view of the Committee, is the necessary standard of protection for children.

5.5.6. The Irish Centre for Human Rights, NUIG, in its submission, having placed the existence of a defence of mistake as to age in the context of international human rights norms, said

“In CC v. Ireland, the Court stated that proof of guilt requires proof of mens rea guilty mind; therefore, the concept of mens rea requires the availability of a defence of an innocent mind, e.g. mistake of fact as to age.”

5.5.7. This view is not, however, shared by all commentators. Professor Finbar McAuley, Jean Monnet Professor of European Criminal Justice, UCD, disagreed with the necessity to prove mental guilt, even for serious offences. He said, in his oral submission to the Committee,

“The claim that, as a matter of descriptive fact, mental guilt is a necessary condition of criminal liability for real crime is not true.”

Furthermore, the view expressed by the Irish Centre for Human Rights, NUIG, appears to the Committee to ignore the degree of moral guilt necessarily involved in the accused’s failure to ensure that his/her sexual partner was an adult. Such a failure amounts to a failure in an essential moral obligation, and a person who has so failed is not possessed of an innocent mind.

5.5.8. This is the view that animated the Oireachtas in the enactment of the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1935. The Committee considers that the passage of time since that enactment has, if anything, lent further force to this view. Many of the submissions to the Committee have referred to the changing cultural influences that have resulted in an ever earlier sexualisation of young people. This feature of modern society, far fromjustifying provision for a defence of mistake as to age, dictates precisely the opposite course. Because young people are induced and encouraged by media, advertising and other cultural influences to dress, act and behave in a way that is often inappropriate for their age, it is all the more necessary that adults take greater care in their choice of sexual partner. Equally, it is all the less acceptable, given those cultural changes, to enable an accused person to invoke the appearance or behaviour of the victim in their defence. Such things must nowadays be understood as offering little, if any, guidance as to the age of a young person.

5.5.9. The Committee considers it, not only desirable, but essential that the State, by its laws, make proper provision for the protection of young people. The Committee also recognises, of course, that, in all its laws, the State must protect the important constitutional rights of adults, including the right to a fair trial, the presumption of innocence, and the requirement that, before punishment can be imposed, guilt must be proven by the State. There is, to some extent, a tension between these rights. But the Committee considers it essential, in balancing these rights in the context of sexual offences against children, to bear in mind that the accused who has failed to ensure that his/her sexual partner is an adult has failed in an important moral obligation. It remains, of course, for the State to prove this, by proving that the proscribed sexual act(s) occurred and that the victim was below the appropriate age.

5.5.10. While it might be argued that this approach is capable of causing injustice in cases where a genuine mistake occurs, the Committee cannot agree. In the first place, it must be borne in mind that the failure to maintain a regime of adequate protection for children, and specifically one which prevents the cross-examination of child victims of sexual abuse as to their appearance and behaviour, will deter such victims from making complaints. That deterrent, and the consequent impunity of sexual offenders against children, would be a much greater injustice. Secondly, an approach which involves a balancing exercise between the important principle of the presumption of innocence and other important, pressing, and substantial objectives of a free and democratic society, has met with approval in various other jurisdictions and, in particular, in the European Court of Human Rights. The Committee considers that its approach to the issue involves a rational and proportionate response to the important and substantial objective of the protection of children from sexual abuse.

5.5.11. The principal attraction of a regime of absolute protection is that the vast majority of those who are accused plead guilty, thereby sparing the child the ordeal of a trial. Nor does the Committee consider such an outcome to represent any injustice or expression of the futility of defending the allegation. On the contrary, such pleas of guilty are conditional upon the accused’s accepting that the prohibited sexual act had taken place.

5.5.12. The Committee respects the decision of the Supreme Court and must make its recommendations as to how to proceed accordingly. Nonetheless, theCommittee is of the view that there remains a need for legislation enacting a standard of absolute protection for children.

5.5.13. In this regard, the Committee notes the submission of the Director of Public Prosecutions that a “reasonable case can be made for a strict liability offence on grounds of policy” and was further guided by the oral presentation of Dr Imelda Ryan. Asked by the Minister of State at the Department of Health and Children, Deputy Brian Lenihan, about the possibility of fixing an age below which questions of consent or honest mistake should not arise, Dr Ryan said

“We spoke earlier about the different developmental stages throughout childhood. There are different developmental stages throughout adolescence. Using a crude divide, I would suggest there is early adolescence, mid-adolescence and late adolescence. If I were to say where things should be totally forbidden, I would say early adolescence. Mid-adolescence is a greyer area and we come right back to the whole issue of developmental and cognitive abilities.”

5.5.14. Asked by the Committee Chairman, Deputy Peter Power, when early adolescence ends, Dr Ryan said that it ended at the age of 13 or 14. Asked later by Deputy Power about the consequences, not just of precocious sexual activity, but of cross-examination relating to such activity, Dr Ryan confirmed that it had the potential to cause trauma to children, including long-term trauma.

5.5.15. In light of this evidence, the Committee was unanimous in the view that there should be absolute protection for children up to an appropriate age. The Committee has recommended elsewhere in this report that the age of consent should be set at 16, except in the case of sexual activity with a person in authority. As the submissions to the Committee clearly call for absolute protection for children up to an age very close to the age of consent, and so as to avoid any danger of confusion as to what the age of consent is, the Committee considers it desirable to maintain the standard of absolute protection for children up to the age of consent.

The Committee recommends that the defence of mistake as to age should not be available to a person accused of an offence involving sexual activity with a child under the age of 16 years.

5.5.16. The Committee acknowledges that the recommendation just stated requires express constitutional authority in light of the decision of the Supreme Court in CC. This issue is dealt with in Part V of the Committee’s report.

5.5.17. The Committee wishes to record that the foregoing recommendation did not receive unanimous support amongst the members of the Committee. Although all members of the Committee supported the principle of absolute protection for children, there was a minority view, held by the Labour Party, that the defence of mistake of age should be available to teen-aged accusedpersons in respect of offences committed with 14- and 15- year old child victims, provided that the mistake was honest and reasonable, so as to avoid the risk of miscarriage of justice in cases where a genuine mistake had been made.

5.6. Persons in Authority

5.6.1. Adults who are in a relationship of authority with a child, whether it is a family, social, sporting, occupational or religious relationship, and who sexually abuse or exploit that child merit particular opprobrium. An offence in those circumstances is a serious offence, not only because of the nature of the act of abuse itself, but also because of the abuse of the trust that has been placed in the offender. For this reason, persons in positions of authority who offend against children merit more severe sentences than do other offenders. This is reflected in the provisions of the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 2006, and is consistent with previous sentencing practice in this jurisdiction.

5.6.2. That, however, is not the end of the matter. The fact that a person occupies a position of authority may have additional significance. Sexual activity with a minor who is of or above the age of consent (assuming that the age of majority and the age of consent remain different), and over whom the offender stands in a position of authority, is an unacceptable breach of trust. This issue is dealt with in Part III of the Committee’s report.

5.6.3. In light of the recommendations made by the Committee in relation to offences committed by persons in authority, it may be desirable, in the interests of clarity in the law, to provide separately for sexual offences against children committed by persons in authority.

The Committee recommends that consideration be given to providing separately in the law for sexual offences against children under the age of 18 years committed by persons in authority.

6.Sentencing

6.1. The Position under the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1935 and the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 2006

6.1.1. The Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1935 distinguished between the offence of defilement of a girl under the age of 15 years and the offence of defilement of a girl who is of or over the age of 15 years but under the age of 17 years. But that was not the only distinction drawn. In the case of the former offence (section 1) the maximum penalty was penal servitude for life. In the case of an attempt to commit the offence, the maximum penalty, in the case of a first offence, was penal servitude for five years, and in the case of a second or any subsequent conviction, penal servitude for 10 years. In the case of the latter offence, the maximum penalty on a first conviction was penal servitude for five years, and in the case of a second or any subsequent conviction, penal servitude for 10 years. In the case of an attempt to commit that offence, the maximum penalty on first conviction was imprisonment for two years, and in the case of a second or any subsequent conviction, penal servitude for five years.

6.1.2. The Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act, 2006 preserves a number of the key sentencing distinctions identified in the 1935 Act. First, the distinction based on the age of the victim is preserved, as are the specific age brackets adopted in the 1935 Act. In the case of an offence involving a sexual act with a child under the age of 15 years, the maximum penalty is life imprisonment, and that penalty also applies in the case of an attempt.

6.1.3. In relation to offences committed on a child who is under the age of 17 years, the 2006 Act preserves the distinctions drawn in the 1935 Act between the completed offence and an attempt and between a first offender and repeat offenders. The 2006 Act also introduces a distinction, for the purpose of sentence, between a person in authority and other offenders. A person convicted of engaging in a sexual act with a child under the age of 17 is liable to a maximum term of imprisonment of 5 years, or 10 years if he or she is a person in authority. In the case of a second or subsequent conviction, the maximum terms increase to 10 years and 15 years respectively. A person convicted of attempting to engage in a sexual act with a child under the age of 17 years is liable to a maximum term of imprisonment of two years, or four years if he or she is a person in authority. In the case of a second or subsequent conviction, the maximum terms increase to four years and seven years respectively.

6.1.4. The submissions received by the Committee have contained a number of proposals for reform in the area of sentencing. In addition, the Committee has reviewed and considered certain other issues of interest that have arisen in this area.

6.2. “Penetrative Sexual Offences”

6.2.1. At present, the law provides for a maximum sentence of life imprisonment for a person engaging in penetrative sexual activity or aggravated sexual assault, at least in respect of victims under the age of 15 years. The Committee has previously recommended that consideration be given to the enactment of a specific offence of penetration by the penis. Such an offence would represent the most serious form of penetrative sexual activity and ought to be treated at least as harshly as penetrative sexual activity, in general, is at present.

The Committee recommends that, if a specific offence of penetration by the penis is enacted, the maximum penalty should be life imprisonment.

6.3. Age of the Victim and Sentence

6.3.1. The law distinguishes at present, for the purpose of sentence, between cases where the victim is under 15 and those were the victim is under 17. The Committee has previously recommended that consideration be given to re-enacting an offence of strict liability for the purpose of providing absolute protection to children, and envisaged that this offence would apply below the age of 16 years. In those circumstances, the Committee does not see any justification for maintaining a further distinction based on the age of the victim below the age of 16 years. The removal of that distinction, it should be said, would clearly not be for the purpose of reducing the applicable maximum sentence to the lowest common denominator.

The Committee recommends that a single maximum penalty of life imprisonment should apply to an offence of committing, or attempting to commit, a penetrative sexual act on a child under the age of 16 years.

6.4. First Offenders and Sentence