|

|

|

Tithe an Oireachtais An Comhchoiste um Dhlí agus Ceart, Comhionannas, Cosaint agus Cearta na mBan Turascáil Eatramhach ar Thuarascáil an Coimisiúin Fiosrúcháin Neamhspléach faoi Dhúnmharú Seamus Ludlow Samhain 2005 Houses of the Oireachtas Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights Interim Report on the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Murder of Seamus Ludlow November 2005 Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights. Interim Report on the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Murder of Seamus Ludlow ContentsInterim Report Appendices A. Orders of Reference and Powers of the Joint Committee B. Membership of the Joint Committee C. Motions of the Dáil and Seanad D. Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the Murder of Seamus Ludlow E. Observations made on Appendix D by former Commissioner Wren and Mr. Justice Barron Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights. Interim Report on the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the murder of Seamus Ludlow. The Joint Committee wishes to extend its deepest sympathy to the relatives of Mr Seamus Ludlow who was killed in 1976. I, Seán Ardagh T.D., the Chairperson of the Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights, having been authorised by the Committee to submit this Report, do hereby present and publish a report of the Committee entitled ‘Interim Report on the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the murder of Seamus Ludlow’. This report was received by the Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights `on Thursday, 3 November 2005. In accordance with the referral motions by Dáil and Seanad Éireann today, the Committee has decided to establish a Sub-Committee to consider, including in public session, the report and to report back to the Joint Committee, in order that the Joint Committee can report back to the Houses of the Oireachtas by 31 March, 2006. As part of the consideration of the report, the Committee intends that the Sub- Committee will invite submissions from interested persons and bodies and hold public hearings, in January 2006, with a view to producing a final report on the matter. The report will detail any submissions received, the hearings held, and such comments, recommendations or conclusions as the Committee may decide to make, and the said report will be published.  Seán Ardagh T.D., Chairperson, 3rd November 2005. Appendix AOrders of Reference .JOINT COMMITTEE ON JUSTICE, EQUALITY, DEFENCE AND WOMEN’S RIGHTS. Dáil Éireann on 16 October 2002 ordered:

Seanad Éireann on 17 October 2002 ordered:

JOINT COMMITTEE ON JUSTICE, EQUALITY, DEFENCE AND WOMEN’S RIGHTS.POWERS OF THE JOINT COMMITTEEThe powers of the Joint Committee are set out in Standing Order 81(Dáil) and Standing Order 65 (Seanad). The text of the Dáil Standing Order is set out below. The Seanad S.O. is similar.

SCOPE AND CONTEXT OF COMMITTEE ACTIVITIES.The scope and context of activities of Committees are set down in S.O. 80(2) [Dáil] and S.O.64(2) [Seanad]. The text of the Dáil Standing Order is reproduced below. The Seanad S.O. is similar.

Appendix B

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputies | Seán Ardagh (FF) (Chairman) |

Senators |

Maurice Cummins (FG)3 |

Motions of the Dáil and Seanad

Tá Dáil Éireann tar éis an tOrdú seo a leanas a dhéanamh:

“Go n-iarrann Dáil Éireann ar an gComhchoiste um Dhlí agus Ceart, Comhionannas, Cosaint agus Cearta na mBan, nó ar Fhochoiste den Chomhchoiste sin, breithniú a dhéanamh, lena n-áirítear breithniú i seisiún poiblí, ar an Tuarascáil ón gCoimisiún Fiosrúcháin Neamhspleách faoi dhúnmharú Shéamuis Ludlow, agus ar na tuairimí arna dtabhairt ag an gCoimisinéir Wren agus ag an mBreitheamh Barron ar an gcéanna, agus tuairisc a thabhairt do Dháil Éireann roimh an 31 Márta, 2006:–

—maidir le Tuarascáil an Choimisiúin Fiosrúcháin Neamhspleách faoi dhúnmharú Shéamuis Ludlow agus leis na tuairimí arna dtabhairt ag an gCoimisinéir Wren agus ag an mBreitheamh Barron ar an gcéanna d’fhonn cibé moltaí a dhéanamh is cuí leis an gCoiste agus d’fhonn aon athruithe is gá a dhéanamh ar fhorálacha reachtacha; agus

—maidir leis na hathruithe reachtacha agus eile, más ann, a bhfuil gá leo i ndáil le fógra a thabhairt do na neasghaolta i dtaobh ionchoisní maidir le dúnmharuithe nó básanna in imthosca amhrasacha.

Dáil Éireann has made the following order:

That Dáil Éireann requests the Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights, or a sub-Committee thereof, to consider, including in public session, the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the murder of Seamus Ludlow, and the observations made thereon by former Commissioner Wren and Mr. Justice Barron, and to report back to Dáil Éireann by 31st March, 2006 concerning:–

—the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the murder of Seamus Ludlow and the observations made thereon by former Commissioner Wren and Mr. Justice Barron for the purposes of making such recommendations as the Committee considers appropriate and any changes to legislative provisions; and

—the legislative and other changes, if any, required in relation to the notification to the next of kin of inquests in relation to murders or deaths in suspicious circumstances.”

Tá Seanad Éireann tar éis an tOrdú seo a leanas a dhéanamh:

“Go n-iarrann Seanad Éireann ar an gComhchoiste um Dhlí agus Ceart, Comhionannas, Cosaint agus Cearta na mBan, nó ar Fhochoiste den Chomhchoiste sin, breithniú a dhéanamh, lena n-áirítear breithniú i seisiún poiblí, ar an Tuarascáil ón gCoimisiún Fiosrúcháin Neamhspleách faoi dhúnmharú Shéamuis Ludlow, agus ar na tuairimí arna dtabhairt ag an gCoimisinéir Wren agus ag an mBreitheamh Barron ar an gcéanna, agus tuairisc a thabhairt do Seanad Éireann roimh an 31 Márta, 2006:–

—maidir le Tuarascáil an Choimisiúin Fiosrúcháin Neamhspleách faoi dhúnmharú Shéamuis Ludlow agus leis na tuairimí arna dtabhairt ag an gCoimisinéir Wren agus ag an mBreitheamh Barron ar an gcéanna d’fhonn cibé moltaí a dhéanamh is cuí leis an gCoiste agus d’fhonn aon athruithe is gá a dhéanamh ar fhorálacha reachtacha; agus

—maidir leis na hathruithe reachtacha agus eile, más ann, a bhfuil gá leo i ndáil le fógra a thabhairt do na neasghaolta i dtaobh ionchoisní maidir le dúnmharuithe nó básanna in imthosca amhrasacha.

Seanad Éireann has made the following order:

That Seanad Éireann requests the Joint Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women's Rights, or a sub-Committee thereof, to consider, including in public session, the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the murder of Seamus Ludlow, and the observations made thereon by former Commissioner Wren and Mr. Justice Barron, and to report back to Seanad Éireann by 31st March, 2006 concerning:–

—the Report of the Independent Commission of Inquiry into the murder of Seamus Ludlow and the observations made thereon by former Commissioner Wren and Mr. Justice Barron for the purposes of making such recommendations as the Committee considers appropriate and any changes to legislative provisions; and

—the legislative and other changes, if any, required in relation to the notification to the next of kin of inquests in relation to murders or deaths in suspicious circumstances.”

PRESENTED TO AN TAOISEACH ON 19 OCTOBER 2004

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE

APPENDICES

Seamus Ludlow, a 47 year-old, unmarried forestry worker from Thistle Cross, Dundalk, Co. Louth, was killed in the early hours of the morning on 2 May 1976. He was shot a number of times. To date, no one has been charged in relation to his death.

Towards the end of 1995, members of the Ludlow-Sharkey family received information from a journalist to the effect that a group of loyalist extremists from Mid-Ulster were responsible for Seamus Ludlow’s murder. Over a series of meetings, the journalist named specific persons whom he believed should have been suspects for the murder. He suggested that the family hold a press conference, and also contact the Garda Commissioner with this information.

On 2 May 1996, the twentieth anniversary of Seamus Ludlow’s death; a press conference was held by the family in Buswell’s Hotel, Dublin. A letter was also sent to the then Garda Commissioner Patrick Culligan. The letter expressed concern at the failure to effect a prosecution in the case, and at “the general conduct of the investigation by the Gardaí at the time.” In particular, it was said that in the period following the murder, the family had been led to believe by individual Gardaí that republican paramilitaries were responsible. The letter concluded:

“We would greatly appreciate, therefore, if you as Garda Commissioner could see your way to order a new investigation into the murder with a view to bringing to justice those responsible for this terrible crime. The Ludlow- Sharkey family pledge its full and total co-operation in any such new investigation and undertake to provide the Gardaí with the name of the person believed to be the killer. We should point out however that we understand the Gardaí already possess this information.”

A new investigation was ordered by the Commissioner, and this re-activation of the case brought to light information received from the RUC in 1979 concerning four loyalist suspects for the killing. The RUC had also offered to arrange interviews with two of the suspects; but it seems that the offer was not taken up at the time.1

When this was brought to the attention of the Comissioner in 1997, contact was made with the RUC and the four men were arrested by RUC officers in February 1998. The four, whose names were not among those given to the Ludlow-Sharkey family by the journalist in 1995/96, were interviewed and released. A file was then sent to the Director of Public Prosecutions in Northern Ireland for a decision on whether charges should be preferred against these men.

On 10 April 1998, an agreement, known as the ‘Good Friday Agreement’ was reached as a result of multi-party talks under the Chairmanship of United States Senator George Mitchell, former Finnish Prime Minister Harri Holkeri and Canadian General John de Chastelain. The Agreement was ratified by popular referendum in this State and in Northern Ireland on 22 May of that year.

In response to sections of the Agreement that proclaimed the need for the suffering of victims of violence to be recognised and addressed, a Victims Commission was set up in this State. It was asked:

“To conduct a review of services and arrangements in place, in this jurisdiction, to meet the needs of those who had suffered as a result of violent action associated with the conflict in Northern Ireland over the past thirty years and to identify what further measures need to be taken to acknowledge and address the suffering and concerns of those in question.”2

In a report published in July 1999, it was acknowledged that there was a widespread demand to find out the truth about specific crimes for which no one had been made amenable. The murder of Seamus Ludlow was singled out for attention in this regard.

At the time of publication of the report, the Director of Public Prosecutions in Northern Ireland had not yet made a decision as to whether prosecutions would be initiated in the Ludlow case. With that in mind, the report concluded:

“Because a file on this case is now with the DPP in Northern Ireland, I am anxious that no recommendation of mine should endanger the prosecution of any guilty party. At the same time I am aware of the family’s strong wish that the full truth of the case should be brought to light. I am swayed by their argument that a criminal trial will not necessarily bring out the full facts of the case. I recommend that an enquiry should be conducted into this case along the lines of the enquiry into the Dublin-Monaghan bombings. To avoid compromising any criminal prosecution, this inquiry should not publish its report until any prosecution has finished, unless no prosecution has been initiated before the completion of the inquiry or within twelve months, whichever is the later.”

As will be seen, the DPP in Northern Ireland subsequently decided not to initiate any prosecutions in relation to the Ludlow murder.3

Arising from the recommendations of the Victims Commission, the Government set up the present Commission of Inquiry with former Chief Justice Liam Hamilton as Sole Member. Mr Hamilton began his duties on 1 February 2000 but was forced to resign on 2 October 2000, owing to ill health. The Government appointed former Supreme Court judge Henry Barron in his place.

Initially, the Inquiry received terms of reference in relation to two incidents – the Dublin / Monaghan bombings of 17 May 1974 and the bombing of Kay’s Bar, Dundalk on 19 December 1975. At a later date, the Inquiry agreed to report also on the shooting of Seamus Ludlow, under the following Terms of Reference:

To undertake a thorough examination, involving fact finding and assessment, of all aspects of the killing of Seamus Ludlow, including:

Unlike the two earlier reports of this Inquiry, the issues to be investigated were relatively clear-cut. The Inquiry had to deal with three separate periods of Garda investigation. The first period, in 1976, concerned the original investigation into the murder.

The second period was in 1979-80, and dealt with the receipt of information concerning four named suspects for the murder, and what inquiries were made thereafter.

The third period commenced in 1996 and ended in 1999 with the decision of the Director of Public Prosecutions in Northern Ireland not to institute any proceedings against the suspects. This period dealt with the eventual arrest and questioning of the suspects, and also with Garda inquiries into the reasons why the information in 1979 was not followed up.

The Inquiry has sought to examine every piece of documentation relating to the murder and subsequent investigations. In that regard it has received full co-operation from An Garda Síochána, the Department of Justice and other Government Departments.

Meetings were held with members of the Ludlow-Sharkey family. The Inquiry sought to interview every Garda officer who participated in the original and subsequent investigations, as well as those officers and Government officials who received, or ought to have received, information about the case at different stages during the past three decades. In relation to material held outside this jurisdiction, the Inquiry entered into correspondence with the Northern Ireland Office and the PSNI.

Before dealing with the information received from An Garda Síochana, it may be helpful to summarise the internal structure of the police force at that time. The force was divided into seven branches of which the following were relevant to the investigation into Seamus Ludlow’s murder:

C1: |

Crime Ordinary - dealt with indictable offenses, and extradition requests from countries other than the United Kingdom. It was mainly responsible for investigating serious crime in the Dublin area. |

C3: |

Security & Intelligence - dealt with subversive or politically motivated crime. Any intelligence received by any Garda officer in that regard was filtered through C3. It also acted as the main channel of communication between the RUC and An Garda Síochána. The Special Detective Unit (SDU), also known as Special Branch, also came under the control of C3. Based in Dublin, it was tasked with checking up on intelligence received by C3 concerning subversives active in the Republic. Although SDU was a subset of C3, its members were not permitted as a rule to deal directly with the police in Northern Ireland. This was done by others in C3. It should be noted that the principal function of C3 was to gather intelligence: the investigation of specific crimes was the purview of C1 and / or the Technical Bureau (see below). |

C4: |

The Technical Bureau - handled forensic, ballistic, photographic and mapping duties in all major investigations. It was based in Dublin. It also incorporated a specialised Murder Investigation Unit (colloquially known as the Murder Squad) which operated with a wide investigative brief on a countrywide level. Although given it’s own branch number, the Technical Bureau ultimately came under the control of Crime Ordinary (C1). It was run by a Chief Superintendent, who reported to an Assistant Commissioner. |

With regard to the work of this Inquiry, An Garda Síochána provided, as before, all relevant files in their possession. These included the original investigation file, with its investigation report and accompanying statements; the Security and Intelligence (C3) file, and a limited number of documents from the Technical Bureau. The Inquiry was also furnished with a number of reports written by Chief Superintendent Ted Murphy during the period 1996-99, when he was conducting enquiries into the manner in which the original investigation was carried out, and into other issues raised by the Ludlow-Sharkey family.

Some Garda documents are either missing or were never brought into existence. For example, there are no Security and Intelligence (C3) files on three of the suspects about whom information was received from the RUC in 1979.4 There was a file on the fourth suspect that had been opened in 1976 as a result of unrelated information received from the RUC, but unfortunately it is missing.

The Inquiry was given to understand that each of the sections of the Technical Bureau – including the Murder Investigation Unit - made and maintained their own files. However, searches of Garda archives found no files from the Murder Investigation Unit nor the Fingerprint section for the relevant period, and apparently incomplete files from the Ballistics section. Some exhibits are missing, including two of the bullets found at the murder scene, and photographic records of certain fingerprints taken at the scene.

As will be seen, An Garda Síochána also assisted the Inquiry with requests for documentation from the PSNI.

The Inquiry first made contact with the Department of Justice concerning Ludlow on 30 May 2002. In response, the Department supplied the Inquiry with two files numbered S39/98 and S57/99. The first file begins with cuttings of newspaper articles from the Sunday Tribune dated 8 and 15 March 1998, in which the existence of the four suspects was revealed for the first time to the general public. The other file begins in November 1999 with a request from the Ludlow-Sharkey family for an inquiry into the murder. Neither of the two files related to the original 1976 investigation, nor to the 1979-80 period, when the information on the suspects first came to the attention of An Garda Síochána.

On 18 June 2002, the Inquiry wrote seeking confirmation that no contemporaneous files on the murder could be found. This request was repeated in a letter of 17 October. A reply from the Security & Northern Ireland Division of the Department dated 15 November 2002 contained the following:

“Contemporary file on the murder of Seamus Ludlow

You requested that this file be forwarded to you. However, after a thorough search I have found no record of or reference to such a file or files having been opened.”

On 22 January 2003 the Department wrote again, indicating that a file on the death of Seamus Ludlow had been found in the 72/ series (a classification dealing with autopsies and crime statistics). The letter continued:

“A search was made of the register of that series and, as a result, the following files have been identified:

(i) 72/17/142 ‘Mr Seamus (James) Ludlow, Culfore Cottages, Culfore, Ravensdale, Dundalk, Co. Louth: Death of’ which contains a request for an autopsy on the victim and a copy of the Garda file on the case…”

The Inquiry wrote again on 28 November 2003, requesting a further search for original files. This search was carried out by Department officials, but with negative results, as a letter of 26 February 2004 made clear:

“This search included the checking of both the electronic and paper-based file registers held by the Department’s Security and Northern Ireland Division, which would have dealt and continues to deal with this matter, as well as the Department’s general file register.

The search has revealed no evidence that any other files exist – or were ever opened – on the murder of Seamus Ludlow, other than the three files already forwarded to you.”

It is clear from the above that there was a Departmental file opened on the death of Seamus Ludlow, which contained a copy of the Garda investigation file. But no additions were made to it when the Gardaí received information from the RUC regarding suspects in 1979: nor was a new file opened on the matter. Given that the publication of similar information in the Sunday Tribune articles of March 1998 led to the opening of a new file, it is hard to understand why the same was not done in 1979 - assuming that this information was indeed passed to the Department.

As a reading of this report will make clear, there should be considerable documentation in the possession of the RUC concerning the murder of Seamus Ludlow.

The Inquiry wrote to Assistant Chief Constable Raymond White of the PSNI on 29 April 2002, setting out the basic facts of the Ludlow case and seeking “any files, data or information you can provide relevant to the death of Seamus Ludlow and to the terms of reference enclosed.” This letter was acknowledged by Asst Chief Constable White’s successor, Asst Chief Constable C.C.K. Albiston, on 15 May.

The Inquiry wrote again to the PSNI on 21 May 2002, seeking in particular, any files concerning the information given to An Garda Síochána in 1979 and any documents relating to the questioning of Seamus Ludlow’s brother-in-law Kevin Donegan by British Army officers in May 1976. Reminders were sent on 10 July, 31 July and 19 November 2002.

On 21 November 2002, Asst Chief Constable Albiston replied as follows:

“I am sure that you will appreciate that extensive enquiries have been necessary to assemble the information which you seek.

I hope soon to be in a position to furnish a report to the Northern Ireland Office who will then be in a position to forward such material as they deem appropriate.”

Thereafter, the Inquiry directed its requests for information to the Northern Ireland Office. On 9 June 2003, a report from the PSNI was annexed to a letter from the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland. The report contained no new information concerning the suspects named to Gardaí in 1979. It also stated that no records had been found concerning the questioning of Kevin Donegan.

On 11 March 2004, the Inquiry was informed by the Director of Public Prosecutions that it might be possible for An Garda Síochána to obtain relevant material in the possession of the PSNI “through the machinery of judicial co-operation.”5 The Inquiry subsequently wrote to the Garda Comissioner asking that this procedure be availed of. Reminders were issued on 14 July and 2 September.

On 30 September 2004, a copy of the RUC investigation file submitted to the DPP for Northern Ireland in October 1998 was passed from the PSNI to the Inquiry via An Garda Síochána. The file contained a substantial amount of material relating to the interviewing of suspects in 1998; but no documentation from 1977, when information on the suspects was first received by the RUC Special Branch.

Contact was made regarding the Ludlow case with the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, the Right Hon. Dr John Reid MP in a letter dated 29 April 2002. On 21 May 2002, a further letter from the Inquiry drew attention to the questioning of Kevin Donegan by British Army officers.

Although receipt of these letters was acknowledged, no substantive replies were forthcoming. On 19 November 2002, the Inquiry wrote again to the Northern Ireland office, setting out the letters to which replies had not been received.

The first substantive response to the Inquiry’s requests for information was contained in a letter from Dr Reid’s successor, the Right Hon Paul Murphy MP, dated 30 November 2002. He wrote:

“You asked for any material we were able to locate on the murder of Seamus Ludlow. I understand that you have also contacted PSNI Crime Department on this and you will receive a separate response regarding any investigation papers they hold. However, as far as Government records are concerned, the MoD have found three references to this in 3 Brigade’s intelligence summaries for the period.”

Quotations from the above documents then followed. The first, headed INTSUM No 18/76 for the period 26 April to 3 May 1976 and dated 4 May 1976, speculated as to possible UVF involvement:

“The threat from Mid-Ulster UVF to border areas in the Republic continues. The mysterious death of Seamus Ludlow may be indicative of future UVF tactics although there are no reports to substantiate that he was killed by extreme Protestants… The corpse of the late Seamus Ludlow was found in a laneway about half a mile from his home… He had been shot in the hand once and 3 times in the side. He has no trace in this office. It is too early to say whether any terrorist organization was involved but it is worth noting that the Mid-Ulster UVF has openly talked about apprehending PIRA suspects in border areas; this occurred on BBC Panorama last year. They have the capability and cross-border activity is expected from them.”

The second extract, from INTSUM No 19/76, dated 10 May 1976, simply noted a statement by Gardaí that the weapons carried by 8 SAS officers arrested near Omeath, Co. Louth on 6 May were in no way related to the weapons used to kill Seamus Ludlow.

The final extract, from INTSUM No 20/76, had no further information concerning the killing, but expressed an opinion that the fact that Irish security forces were following up the Ludlow murder would make further cross-border activity less likely.

The Inquiry wrote again to the Northern Ireland Office on 17 February 2003, pointing out that its request for information on the questioning of Kevin Donegan had not been answered. The Secretary of State for Northern Ireland responded on 9 June 2003 stating:

“I hope that this response will address all the issues you have raised. I would emphasize again that I do wish to co-operate with your investigation as fully as possible.”

The letter continued:

“You are seeking information on Seamus Ludlow, specifically in relation to the questioning of his brother-in-law by the Army in 1976. The Ministry of Defence has already provided what information they have on Ludlow, which I included in my letter of 30 November 2002… We do not have any further information to add to this.”

The Inquiry queried this apparent lack of documentation in a further letter dated 28 November 2003, but received the same response in reply.6 A final attempt to elicit information under this heading was made on 14 July, but had not been replied to at the date of completion of this report.

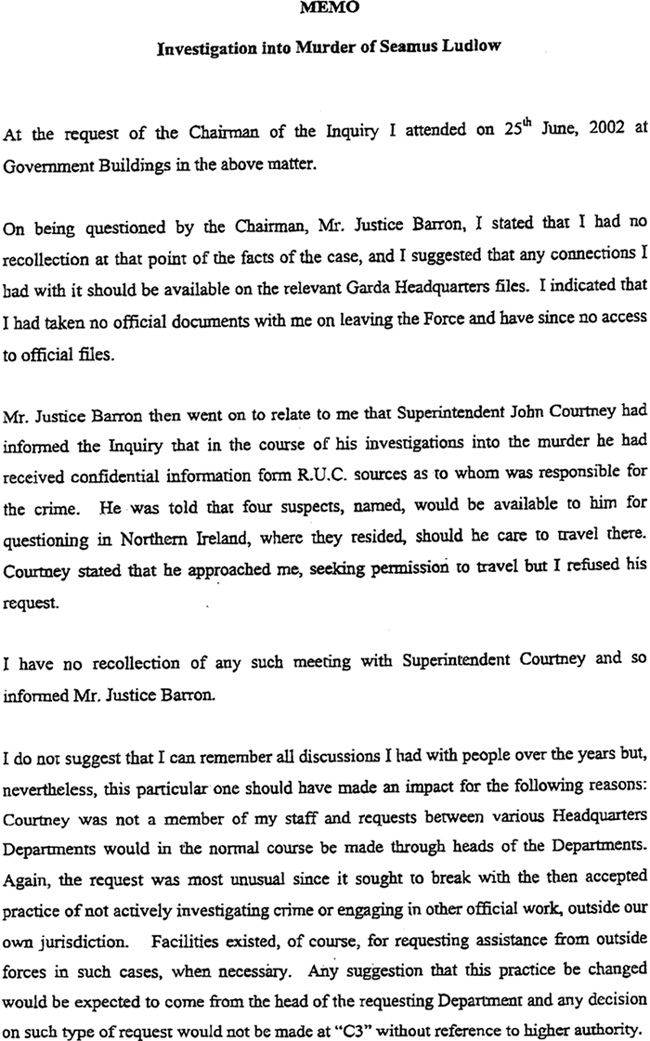

The Inquiry has contacted a large number of Garda officers, who would have been stationed at Headquarters or at Dundalk in 1979 when the information concerning the four suspects was received. Very little information has been received under this heading. Most of those contacted had no memory of the crime itself, and those that did, had no recollection of the information received concerning suspects, although it is apparent from the Inquiry’s work that very few people would have known of that information.

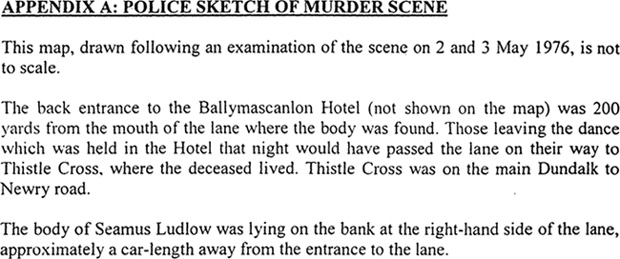

Seamus Ludlow’s body was found at about 3 p.m., lying on a briar-covered bank at the side of a narrow lane, about 3.5 miles from Dundalk town. The Garda report described the location as follows:

“To gain access thereto, one would travel 2.5 miles from Dundalk along the main Dundalk / Newry Road, turn right at Thistle Cross down a road known locally as the Bog Road, for a distance of about one mile. At this point a laneway measuring a distance of four-tenths of a mile is located to the left of this road as one approaches from Thistle Cross. The body of the deceased was found lying on some hedging on the right hand side of this laneway about ten yards down. The rear entrance to Ballymascanlon Hotel is located about 100 yards further along the Bog Road.”7

The position in which the body was found suggested that it had been thrown there after the deceased was killed.

The two persons who discovered the body left the area immediately and reported it to Gardaí in Dundalk at 3.16 p.m. A radio message was then sent to Sgt Jim Gannon, who was in a patrol car near the area along with another Garda officer. The two men arrived at the scene at 3.20 p.m., found the body and contacted Dundalk Garda station. Within minutes, other Gardaí arrived. The area was sealed off and traffic diversions set up.

At 4.30 p.m., the scene was visited by a priest from Dundalk. At 5 p.m., a doctor from Dundalk visited the scene and confirmed that the victim was dead.

Members of Seamus Ludlow’s family had been out looking for him since the morning. At 5.15 p.m. his brother Kevin Ludlow was stopped by Gardaí at the entrance to the Bog Road:

“He stopped me and told me I couldn’t go up because there was a bit of an accident. The Guard then explained that it wasn’t really an accident, but that a body had been found. I explained about my brother being missing and he said then I could go on… As soon as I saw the body I knew it was Seamus and said ‘That’s poor Seamus alright’.”8

Seamus Ludlow lived in a house at Thistle Cross, along with his sister, Annie Sharkey, her husband and their ten children. His mother also lived with them.

He had spent his working life as a labourer in various situations. At the time of his death, he was employed in a local sawmill at Ravensdale Wood, Dundalk. He was said by family, friends and colleagues to have been a quiet, unassuming man whose life revolved around work and home. His social life consisted of regular visits to various pubs in Dundalk and occasionally to the Border Inn, Carrickcarnan. Although comfortable in company, it was said that he usually drank alone. On Saturdays, when he got a half-day from work, he would usually head straight to the Border Inn; arriving home any time between 6 and 9 p.m. If he did not do that, he would usually go into Dundalk in the evening.

He was also known in Dundalk for his charitable work: for many years he acted as ‘Santa Claus’ for children in a Dundalk housing estate.

Other than a preference for the Fine Gael party, Seamus Ludlow had no known political affiliations, and nothing whatsoever to connect him with any subversive organisation. In fact, members of his family recalled that he was firmly opposed to the IRA and similar groups, and regularly made this known to his teenage nieces and nephews.

It was established that the deceased was working at the sawmill on Saturday, 1 May 1976 until lunchtime. He arrived home at about 2 p.m. and had a light meal. He left the house at 3 p.m., saying he was going to the Lisdoo Arms, Dundalk for a few drinks.

He remained at the Lisdoo Arms until about 9.15 p.m., when he left in the company of one John Dunne. The two men went to the Horse and Hound pub, Linenhall St, Dundalk for one drink, then left to go to the Vine, another pub in the town. John Dunne left there at about 11.15 p.m. A number of witnesses recalled the deceased drinking in the Vine until 11.30 p.m. One witness said they saw him leaving at around that time. He was alone.

According to family members, friends and others who knew him, it was his usual practice to ‘thumb’ a lift home. The manager of the Lisdoo Arms told Gardaí:

“I often saw him thumbing lifts out to his house at the Lisdoo Arms and also at Newry Bridge. He very seldom asked anyone for a lift home, even if someone from near him was in the bar. He seemed to prefer to thumb.”9

A number of witnesses, including some who knew him well, told Gardaí that they saw him in the vicinity of Newry Bridge at various times between 11.50 p.m. and 12.15 a.m. On the other hand, other witnesses who knew the deceased and who crossed Newry Bridge before or after midnight stated that they did not see him there.

No one claimed to have seen him being offered or accepting a lift; but as there were no sightings of him in the Newry Bridge area after 12.30 a.m., it seems reasonable to suppose that he had been picked up by that time.

According to the investigation report, there was a Garda checkpoint in operation near the Newry Bridge during the relevant time. Registration numbers of cars noted during this time were followed up (mostly with the RUC) but nothing emerged to connect any of them with the murder.

The Garda investigation team went to considerable lengths in their efforts to trace the deceased’s movements on the night in question. Every household on the main and ancillary roads from Newry Bridge to the Border was visited and questionnaire forms were filled out:

“In all, 1,700 questionnaires were completed and processed, but nothing of value was obtained which gave any indication as to how or what time the deceased was picked up, or as to how or what time his body was placed in the position in which it was later found.”10

On the night of 1 May 1976 there was a dance in progress at the Ballymascanlon Hotel, a short distance from the place where the body was found. The dance finished at 1.30 a.m., and a number of people were found to have left the hotel by the rear entrance and travelled along the Bog Road to Thistle Cross, passing the lane where the body was in the process. Four witnesses claimed to have seen a car parked near the lane entrance; but this was contradicted by the evidence of a number of other witnesses. Gardaí re-interviewed three of the witnesses who said they did not see a car, and were satisfied they were telling the truth. The investigation report concluded:

“Without prejudice to the veracity of either party as to whether a car was parked there or not, further enquiries to clear up this point proved negative.”11

One week after the murder, on the night of 8 May, 35 Gardaí mounted checkpoints at various points along the Dundalk / Newry road between 11 p.m. and 3 a.m. This was with a view to interviewing any motorists who may have travelled the same route on the night of the murder. In all, about 1,400 cars were stopped; but no positive information resulted from these inquiries.

The State Pathologist, Dr. John Harbison arrived at the scene of the murder at 7.55 p.m. on 2 May 1976. He carried out a preliminary examination of the body prior to its removal to the Morgue at Dundalk District Hospital, where a full post-mortem was carried out. He described his initial impression of the scene as follows:

“I saw the body of a middle aged male lying on top of a grassy bank beside the laneway with his head uppermost. His feet were on the side of the bank over some briars away from the laneway… The man was clothed in a shirt and pullover, with an overcoat and jacket thrown over the body. The right arm was extended, with the hand lying also among briars and nettles on top of the bank. The body lay on its back…

Preliminary inspection of the body revealed the shirt and pullover pulled up off the abdomen…”

It was clear from the presence of bullet-holes in the jacket and overcoat that the deceased had been wearing them when he was shot: someone (presumably the killers) must have taken them off after he was dead.

As the body was taken down from the bank, a bullet fell from the clothing. Sgt Gannon picked it up and showed it to Dr Harbison before handing it to D/Garda Michael Niland, Ballistics Section, Technical Bureau.

The post-mortem proper was begun at 12.20 a.m.. The clothing was removed and examined by Dr Harbison before being handed to D/Garda Niland. In the course of this, a second bullet was discovered in the deceased’s clothes. This was also taken possession of by D/Garda Niland.

Dr Harbison then examined the wounds to the body and concluded that the deceased had died from shock and haemorrhage as a result of bullet wounds in his heart, right lung and liver. These wounds came from three shots. The fatal shot – that to the heart – came horizontally from the front, from a point slightly to the left of the deceased. The other two shots also came from the front, but much more to the left.

A third bullet was extracted from the victim’s chest by Dr Harbison, and handed to D/Garda Niland. Two samples of blood from the body were also taken: one was kept by Dr Harbison; the other given to Dr Jim Donovan at the State Laboratory.12

The immediate scene and surrounding area were examined by officers from the Ballistics, Fingerprint, Photographic and Mapping sections of the Technical Bureau. The lack of blood stains where the body was found, together with the fact that the deceased’s shoes were clean, suggested that he was shot elsewhere – possibly in a car – before being thrown on top of the hedgerow at the side of the laneway.

The three bullets found in the body and clothing of the deceased were examined by D/Garda Niland, who concluded:

“All these bullets… are copper-jacketed revolver bullets of .38 inch calibre of a type known as .38 Smith & Wesson, and all were discharged from the same firearm.”13

The investigation report stated:

“These bullets were later brought by D/Gda Niland to the Data Reference Centre, Belfast for comparison with their files to establish if they had a similar pattern on record. This comparison proved negative.”

There is no further statement by D/Garda Niland in Garda files, but a handwritten note found in a notebook belonging to D/Inspector John Courtney would appear to suggest that the bullets did not remain in Belfast, but were simply photographed for future reference. The note referred to the three bullets and the circumstances in which they were found, and then stated:

“Data Reference Centre, Herbie Donnelly, photographed and reorded [recorded?] them, on 11/5/76.”

One of the two persons who discovered the body also found a key on the ground nearby. Attempts by Gardaí to trace ownership of it were unsuccessful. According to the investigation report, the condition of the key when it was found suggested that it might have been at the scene for some time.

A hand-drawn map of the murder scene, found in the archives of the Technical Bureau, showed two other items – a man’s black leather glove (right hand) and a bag of dry bread. There was no reference to these items in the investigation report. Their significance, if any, cannot be assessed at this remove.14

The Garda investigation team received no reliable piece of intelligence information as to who might have been responsible for Seamus Ludlow’s death. The investigation report stated:

“Many theories have been put forward suggesting various reasons why the deceased was murdered. Likewise, the same theories have been put forward as to how, why and at what time the deceased was picked up, presumably near the Newry Bridge on the main Dundalk / Newry road.

Those put forward as being responsible include the PIRA, Protestant extremist groups, the SAS, members of the deceased’s family, neighbours of the deceased, and that the deceased was a victim of mistaken identity…

With all the theories available, there is nothing tangible in any of them which bears up to any scrutiny, with the result that one is left in the final analysis with the deceased having last been seen alive in the vicinity of Newry Bridge about 12.30 a.m. on 2-5-76… and then vanish until found dead at about 3 p.m. on the same day, without any apparent reason. In other words, the whole episode appears, at this stage, to be a complete and unresolved mystery.”15

The investigation team quickly established that there was no conceivable motivation – financial, personal or otherwise – for any of Seamus Ludlow’s relatives, neighbours or friends to have been involved in his death. He was not on bad terms with anyone; he had little or no money; and his will bequeathed the house at Thistle Cross to his sister, with whose family he lived.

Suspicion that members of the SAS might have been involved in the murder arose from a separate incident that occurred on the night of 5 May 1976. At 10.40 p.m. a car containing two armed SAS soldiers was stopped at a Garda checkpoint at Cornamucklagh, Omeath, Co. Louth. It was travelling south at the time. The two men were detained and taken to Dundalk Garda Station for further questioning.

At 2.15 a.m. on the same night, two more cars containing a total of six SAS soldiers were stopped at the same checkpoint – again, travelling south. These men were also armed. All six were taken to Dundalk and questioned. The cars involved in the incidents were technically examined, as were the firearms belonging to the soldiers.

In the course of interviewing the soldiers, they were questioned about the murder of Seamus Ludlow. Nothing emerged which might have connected them his death. There was no evidence that they had been in the area on the night of 2 May 1976, and none of the weapons with which they were found at Omeath were of .38 calibre. The investigation report concluded:

“There is no evidence to connect them with this crime.”

An article in the Sunday World of 16 May 1976 speculated that the deceased was killed as a result of mistaken identity. The correspondent, who was based in Dundalk, wrote:

“… I learned from inquiries that the popular sawmill worker, who had no involvement in politics, was the ‘double’ of a top Provisional IRA man who is on the wanted list of both the SAS and the outlawed Ulster Volunteer Force.

The Provisional to whom the dead man bore such a remarkable resemblance served for nine years in the British Army before joining the IRA. He is reckoned to be the Provo’s top marksman.”

The article continued:

“Local people to whom I have spoken say that the sleeves of the murdered man’s coat were ripped out. This could be relevant to the mistaken identity theory, for the Provo marksman they may have thought they had ‘lifted’ is tattooed on both arms.”

As we have seen, the coat sleeves were not in fact ripped out, but the deceased’s coat and jacket were removed from his body after he was killed.

The Garda investigation team identified a man whom they thought most likely to have been the ‘Provo’ referred to in the article – an IRA member and former British Army soldier who had tattoos on both arms. This man was interviewed by D/Gardaí T. Dunne and T. Hynes, who concluded that it would be difficult to mistake the deceased for him.

Efforts were made by Gardaí to get the names of potential suspects for the shooting from the RUC. The investigation report stated:

“Many enquiries have been made through the channels of the RUC in an effort to illicit from them who they thought might be in a position to help us in our enquiries, but whereas we have received the usual co-operation, it must be appreciated that they have neither the time nor the manpower to concern themselves too fully with the problems prevailing on our side, when they are so fully taken up with events up North. Nevertheless, contact is being maintained, and I feel that if anything of a tangible nature should arise, results will be made known to us.”

The importance of maintaining such contact was also emphasised by the Garda Commissioner, Edmund Garvey. In a handwritten note for the Commissioner C3 dated 4 June 1976, he acknowledged receipt of the investigation report and stated:

“Keep in touch with the RUC. Something useful may be forthcoming in time.”

Shortly after Seamus Ludlow’s murder, the Provisional IRA made a statement denying any involvement in his death. At the time the investigation report was written, no information had been received to contradict this.

However, on 1 October 1976 an intelligence report cited an unknown source as stating that Ludlow was murdered by a named Provisional IRA officer from Belfast, who was at that time awaiting trial on firearms charges. It was said that Ludlow was shot because he was believed to be working for British Intelligence.

However incredible this sounded, it required following up: on 14 October a letter was sent to RUC Special Branch, outlining the information received and asking for their views. On 19 October, the RUC replied as follows:

“A low grade source has reported that [Seamus Ludlow] was murdered by the PIRA as they suspected him of passing information to Security Forces in the South.

Ludlow’s brother is also believed to be a member of the PIRA.”

It is worth stressing (a) that the source was low-grade; and (b) that the RUC information accused Ludlow of giving information to the security forces in the State – not to the British security forces, as the Garda informant had alleged.

The information received from the RUC was passed from C3 to the Chief Superintendent in Drogheda, and then to detectives in Dundalk, with a request for observations. On 31 December 1976, a report by D/Sgt Owen Corrigan, Dundalk stated:

“Subject has three brothers and none of them is a member of the PIRA.”

The report promised further enquiries “of a delicate nature” into whether any of the extended family members were IRA sympathisers, and concluded:

“This matter will continue to receive attention by all concerned.”

The last reference to this information in the Garda files was a letter from the office of the Assistant Commissioner, C3 to the Chief Superintendent, Drogheda asking for a report on the result of D/Sgt Corrigan’s further enquiries. There is no response to this on file, which may indicate that the allegations were not regarded as credible.

In any event, the views of senior Gardaí as to who was responsible for Seamus Ludlow’s murder were changed irrevocably in 1979, when information of far greater credibility was received from the RUC. This information, which placed the blame for his death on loyalist subversives, is the subject of the next chapter.

On 30 January 1979, a letter was sent from the RUC Chief Constable’s office to C/Superintendent Michael Fitzgerald, Security and Intelligence (C3), Garda Headquarters, Dublin. It was headed, ‘Murder of Seamus Ludlow at Ravensdale, Co. Louth on 2 May 1976’ and read as follows:

“It has been learned from a source believed to be reliable that the undermentioned members of the Red Hand Commandos (RHC) were involved in the murder of Seamus Ludlow at Ravensdale, Co. Louth on 2 May 1976:

Paul HOSKING, 23 years… Glasgow and formerly of… Comber, Co. Down.

William Richard LONG, 32 years… Comber, Co. Down, at present serving life imprisonment for the murder of David Spratt, 48 Dickson Park, Ballygowan, Co. Down at Comber on 2 June 1976.

Samuel CARROLL, 27 years… Bangor, Co. Down, at present serving a 4-year prison sentence for firearms offences.16

James Reid FITZSIMMONS, 38 years… Killyleagh, Co. Down.

Our headquarters Regional Crime Squad have been informed.”

On 5 February, this information was conveyed by letter from Garda Headquarters to Chief Superintendent R.Cotterell, the Divisional Officer at Drogheda.

On 15 February 1979, Superintendent John Courtney and Detective Sergeant Owen Corrigan travelled to RUC Headquarters in Belfast and met with the head of CID, Chief Superintendent William Mooney. Courtney was at that time Border Superintendent, based at Dundalk Station. He had been promoted in September 1978. Prior to this appointment, he had been a Detective Inspector with the Murder Investigation Unit, Technical Bureau; in which capacity he had assisted Detective Superintendent Dan Murphy with the original 1976 investigation.

In the course of the meeting they were introduced to two RUC Special Branch officers who said they had information regarding the Ludlow murder. In his report of the meeting (dated 15 February but clearly written 2 or 3 days later, as it refers to further information received on 17 February) D/Supt Courtney gave an account of what they were told.

It must be emphasised that Supt Courtney’s report was based on his own recollection of what was said to him by the RUC officers at their meeting: it was not a verbatim transcript of the information given to the RUC by their informant. It is reproduced here solely for the purpose of assessing what information was available to Gardaí in 1979. He wrote:

“On the 15th February 1979 I had a discussion with [two named Special Branch officers]. This meeting took place at Belfast. Both these men related the following. A contact told them that No. (1) Hosking, was involved in a murder in Dundalk some time ago. Hosking and the other three travelled to Dundalk in Fitzsimmons’ car. All the persons mentioned were at the time members of the North Down Volunteers, and they went to Dundalk to shoot some ‘Provo’ at random. They had a snub-nosed Smith and Wesson revolver…

After going to Dundalk they drove around to see if they could see some ‘Provo’. They saw a middle aged man ‘thumbing’ a lift. They took him into the car. They travelled along the road. They ordered this man to get out of the car; he objected because he hadn’t reached his destination. Carroll then shot him: the informant thinks the shooting took place in the car; he is not sure. They got rid of the body and returned home…

Hosking knew he was going on a mission that night, but didn’t know where it was. He asked the others if he could go with them. They allowed him to go, but Carroll wasn’t too happy about him afterwards; he did not trust him…

Number (2) William Long is in prison for his involvement in the murder of a Mr Spratt 2/6/1976. He admitted his involvement in this murder. He has not been interviewed for the murder of Mr Ludlow.17

Number (3) Samuel Carroll did the actual shooting. The weapon used is believed to be in the Bangor area…

Carroll who is in prison for possession of firearms is regarded as a highly dangerous criminal who has committed a number of murders. He would not admit his involvement in any of them. He is regarded as a man who will kill just for the sake of killing.

Number (4) James Reid Fitzsimmons, his car was used in the commission of the murder. Inquiries are being made to establish the present location of his car. It may contain bloodstains or other evidence.

Fitzsimmons is a Corporal in the UDR and is held in high esteem. Following the murder he had a suspected heart attack, but it is thought it was not a heart attack only sheer worry over what they had done to Ludlow. He has not been interviewed for the murder of Mr Ludlow.”

Concerning the provenance and value of this information, D/Supt Courtney wrote:

“[one of the Special Branch officers] is satisfied that this information is true… [He] has this information for the past 18 months and he gave no information or reason to me for not disclosing it before now. But he did say his informant begged him not to interview Hosking and he may have decided not to disclose the information until Hosking had left the country. Hosking left Ireland about 6 months ago.

On the 15th February, 1979 I discussed the matter with D/Chief Supt. Wm. Mooney, Head of CID, Belfast. He informed me that he would give every cooperation in the investigation. He did suggest that Fitzsimmons should be interviewed at the same time as Hosking. C/Supt. Mooney has established through the Scottish Police (on 17/2/79) that Hosking is in Scotland and residing at the address stated.

C/Supt Mooney has stated that he will arrange for [the two Special Branch officers] to travel to Scotland if required. These two detectives would be of assistance if we decide to interview Hosking.”

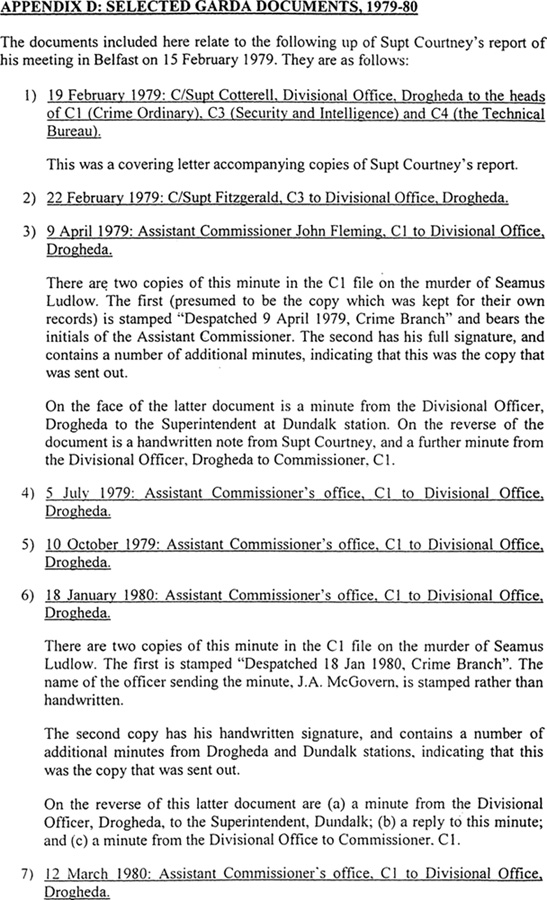

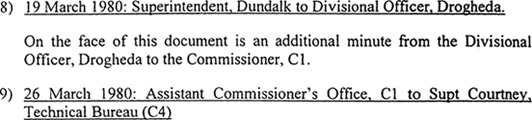

Copies of D/Supt Courtney’s report were sent from C/Supt Cotterell, Drogheda to the heads of C1 (Crime Ordinary), C3 (Security and Intelligence) and C4 (Technical Bureau) on 19 February 1979. The accompanying letter stated:

“For information. Superintendent Courtney on my instructions is discussing the matter fully with D/Superintendent [Dan] Murphy at the Technical Bureau today when further steps to be taken will be decided upon.”

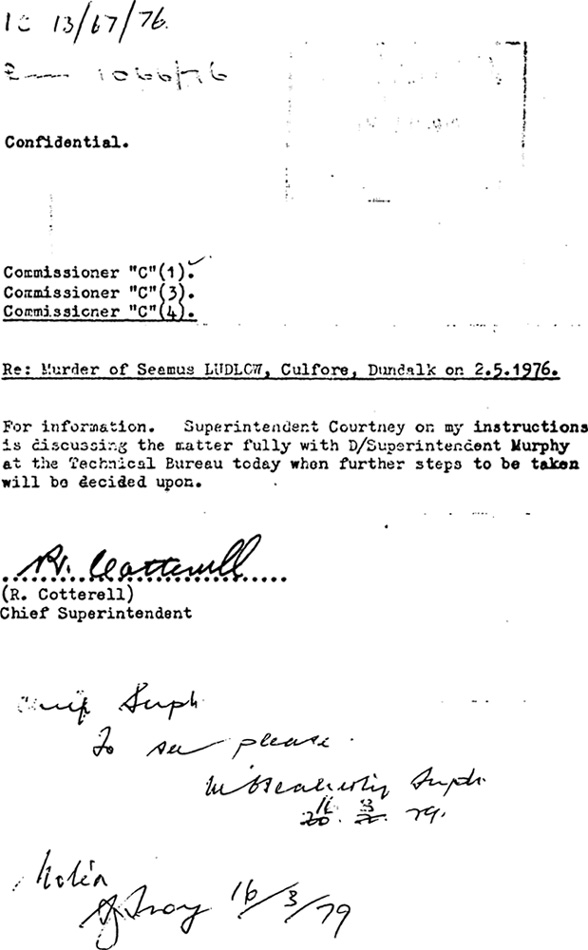

On 22 February, C/Supt Fitzgerald, C3 responded:

“Your correspondence on above subject has been received and noted. Report any further developments.”

On 28 February 1979, a further letter from RUC Headquarters was received by C/Supt Fitzgerald. It read as follows:

“I give hereunder further details of the person[s] named in our letter of 30 January 1979; as requested by Superintendent Courtney, Dundalk.

Paul Hosking: No photograph or description available.

William Richard Long: Height 6’1”; thin build; thin long face; pale complexion; dirty fair hair; green eyes; long straight nose; sometimes wears a short beard. Copy of photograph enclosed.

Samuel Black Carroll: Height 5’8”; slim build; oval face; pale complexion; brown hair; blue eyes. Copy of photograph enclosed.

James Reid Fitzsimmons: No photograph or description available.”18

A copy of this letter, with the attached photographs, was sent from C3 to C/Supt Cotterell in Drogheda on 1 March 1979.

No further information was received concerning the search for Fitzsimmons’ car. It is not known what enquiries were made by the RUC in that regard. On 21 November 2003, the Inquiry wrote to the Northern Ireland Office seeking further information on this, but met with no response.

In his original report, made following his meeting with the RUC on 15 February 1979, D/Supt Courtney stated:

“Comparisons have been made with photographs of the bullets found and taken from Mr Ludlow’s body with the weapon used in the murder of Spratt – the forensic department in Belfast are of opinion that it is not the same weapon. However they will not be definite until they make comparison with one of the bullets found in Ludlow. I would suggest that one of the bullets found in Ludlow be taken to Belfast.”

From this passage, it would appear that the comparison was made prior to the meeting on 15 February, presumably at the behest of the RUC. However, the only written record available to the Inquiry is contained in a letter from Norman Tulip of the Data Reference Centre, Belfast to Superintendent Raymond White, RUC Headquarters dated 6 March 1979. It stated:

“Enquiries from SB (RUC)… reveal an interest in connecting the murder of Ludlow to the revolver used in the murder of D Spratt at Darragh Road, Comber on 2 June 1976. Similar enquiries from Garda Technical Bureau indicate mutual interest North and South.

The murder weapon in the case of Spratt was a .38” Smith and Wesson revolver serial number 943510, submitted as exhibit 9 to NIFSL,19 who gave positive matching with bullets removed from the body of Spratt.

The murder weapon in the case of Ludlow was a .38” revolver with barrel rifled five grooves right hand twist, but no weapon was recovered at the scene or since. Comparisons [were] made by DRC with (a) bullets from the murder of Spratt, (b) bullets from the Smith and Wesson revolver used in the murder of Spratt, and (c) bullet exhibit from the murder of Ludlow. There was no difficulty in matching (a) with (b), but no match could be made between (a)/(b) with (c), and opinion is expressed that the revolver used in the murder of Spratt was not used in the murder of Ludlow.

The revolver used in the murder of Ludlow has however the same rifling characteristics as that used in the murder of Spratt and could be of the same type. Test-fired bullets are available from the Smith and Wesson revolver seized in the Spratt murder, and these can be made available to the Garda should they wish to formulate their own opinion. The revolver has been disposed of, destroyed by the military, and neither it nor further control samples are available.”

It would appear that D/Supt Courtney’s advice that a bullet be sent to Belfast was taken. The Garda Ballistics Section files contain a letter from ‘Herbie’ [presumed to be Herbie Donnelly, Data Reference Centre, Belfast] to ‘Pat’ [D/Insp Pat Jordan, Ballistics Section] dated 28 March 1979 which read:

“Enclosed exhibit which you left after your last visit. Checked against case you suggested. No match confirmed by Victor’s staff.20 Other comparisons also negative.”

On 28 November 2003, the Inquiry wrote to An Garda Síochána asking if there were any exhibits still extant in the relation to the death of Seamus Ludlow from which DNA samples might be obtained. A reply dated 8 March 2004 indicated that there were not.

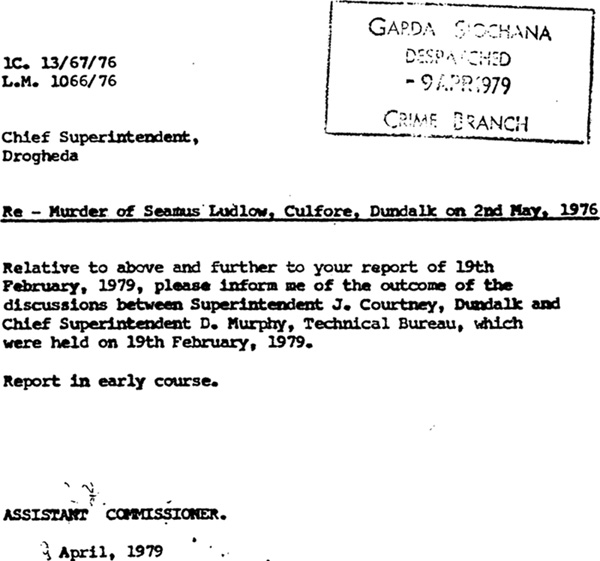

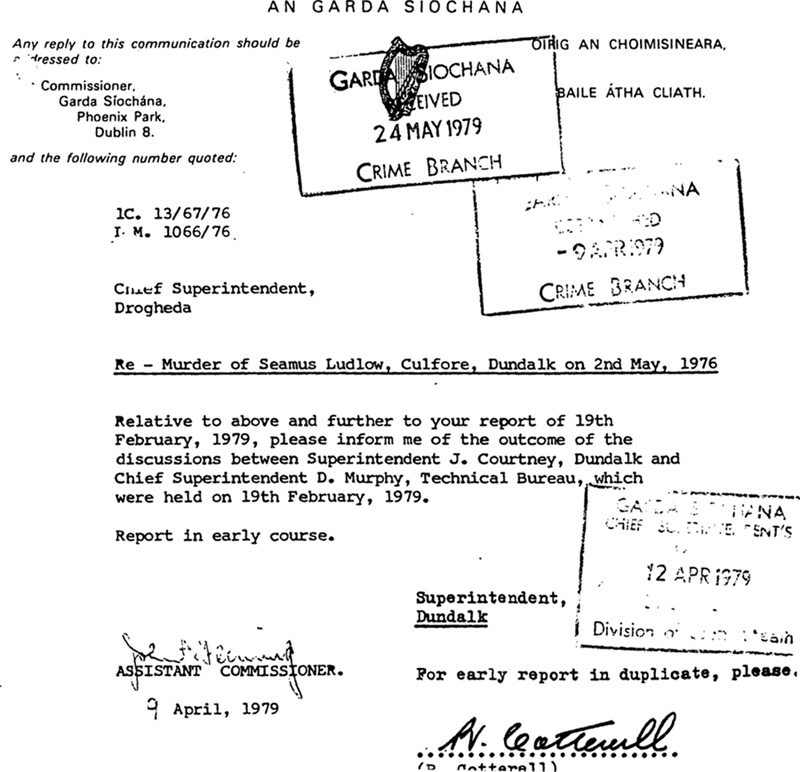

On 9 April, Assistant Commissioner John Fleming, Crime Ordinary (C1) branch, wrote to C/Supt Cotterell enquiring as to the outcome of the discussion between D/Supt Courtney and C/Supt Murphy which was supposed to have taken place on 19 February. The letter ended with the instruction: “Report in early course.” A photocopy of the letter also appears in the Security and Intelligence (C3) file, although it is not stamped, and there is no indication as to when it was received.

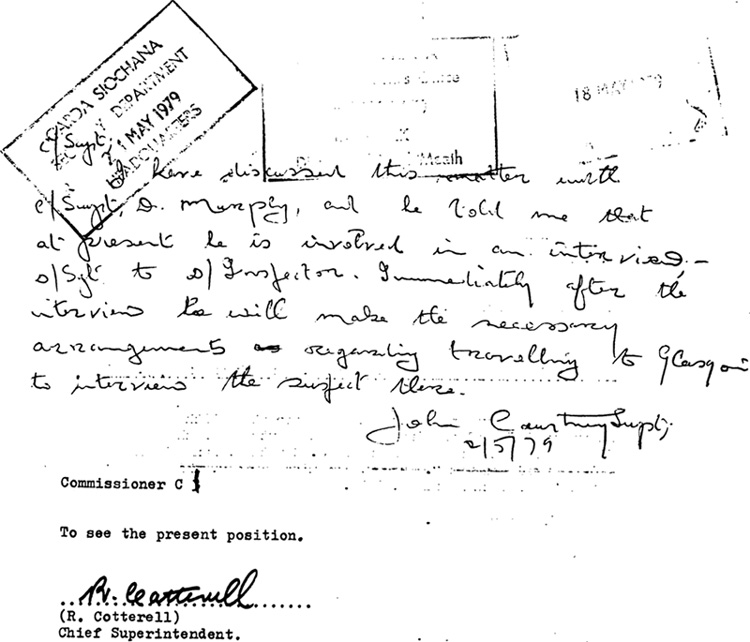

On 12 April, C/Supt Cotterell forwarded this letter to the Superintendent at Dundalk, adding “For early report in duplicate, please.” No reply was received until 18 May 1979, when a handwritten response from D/Supt Courtney stated:

“I have discussed this matter with C/Supt D. Murphy, and he told me that at present he is involved in an interview – D/Sgt to D/Inspector. Immediately after the interview he will make the necessary arrangements regarding travelling to Glasgow to interview the suspect there.”

Although the request for information had come from C1, this note was sent by C/Supt Cotterell to C3. It was received there on 21 May, and forwarded to C1 on 24 May.

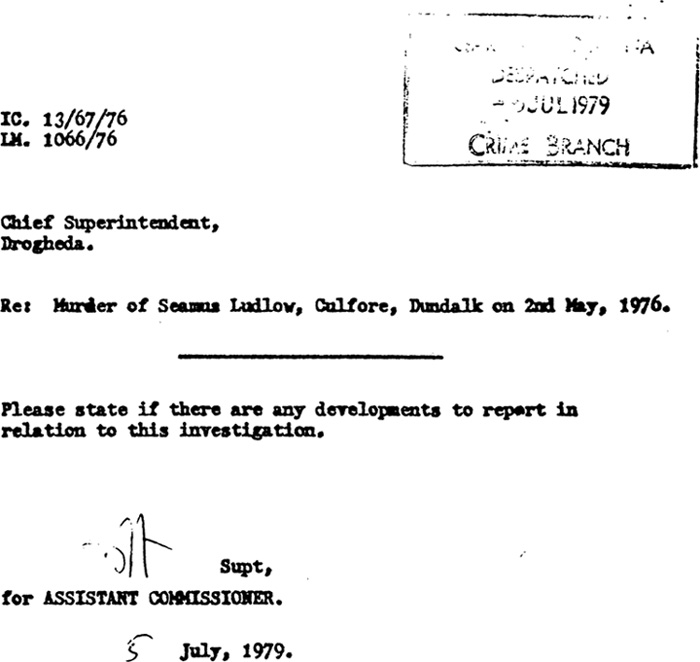

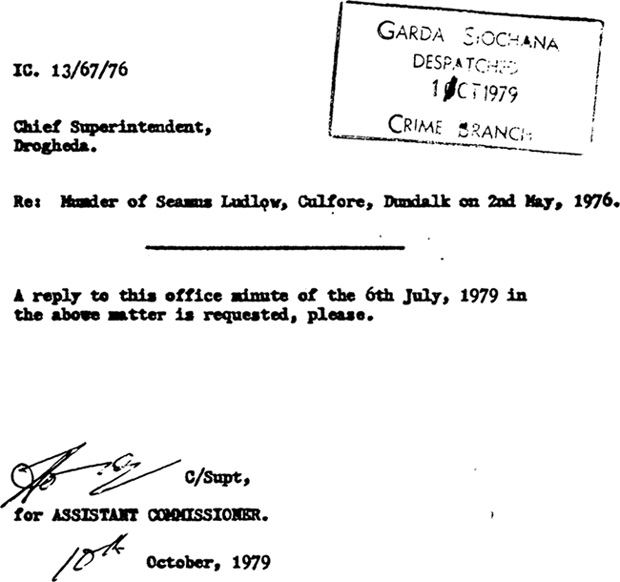

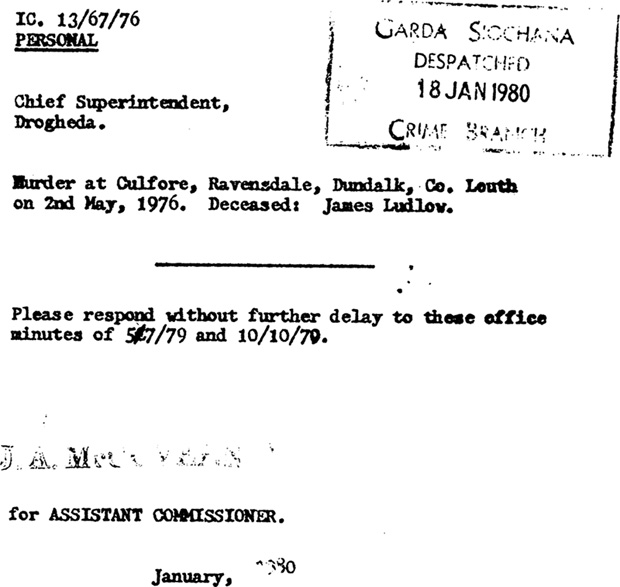

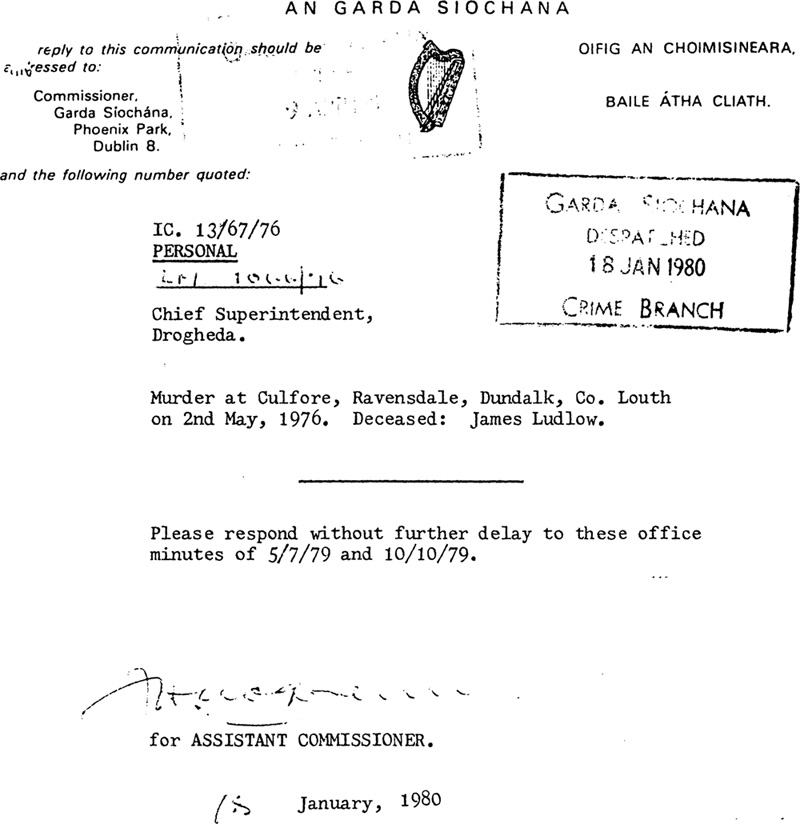

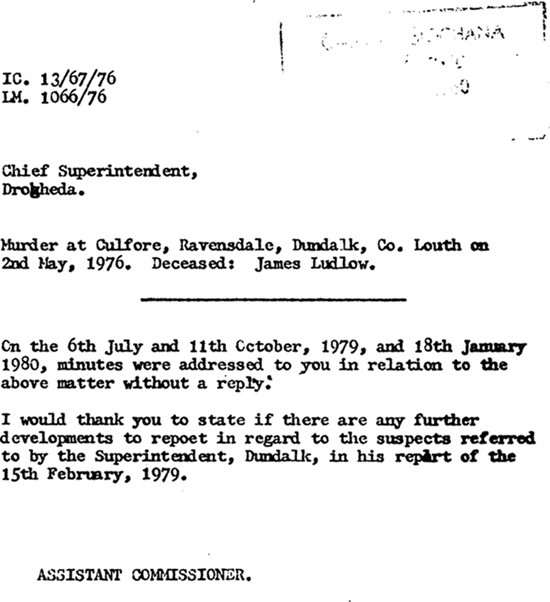

Further notes requesting reports on any developments were sent from C1 to the Chief Superintendent, Drogheda on 5 July 1979, 10 October 1979 and 18 January 1980.

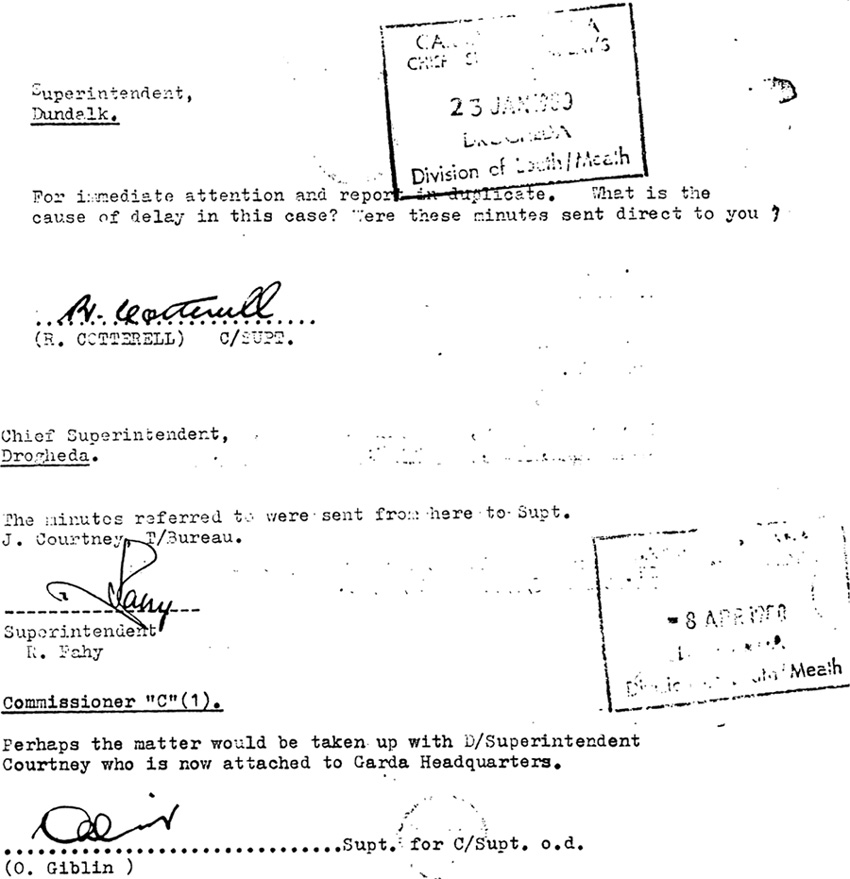

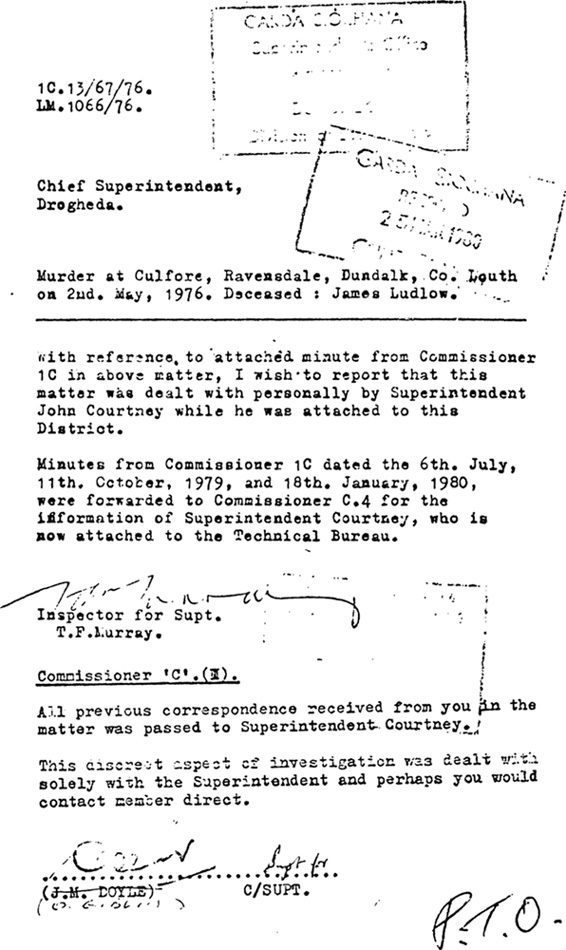

On 23 January 1980 C/Supt Cotterell raised the matter with the Superintendent in Dundalk, Supt Fahy. A response was received from the latter on 8 April, to the effect that the queries had been forwarded to D/Supt Courtney, who in July 1979 had returned from Dundalk to Garda Headquarters, where he was once more attached to the Investigation Section, Technical Bureau (C4).

In the meantime, on 12 March 1980 a further reminder was sent from C1 to Drogheda. Having drawn attention to previous unanswered letters, it concluded:

“I would thank you to state if there are any further developments to report in regard to the suspects referred to by the Superintendent, Dundalk, in his report of the 15th February, 1979.”

A response from the Divisional Office, Drogheda was received by C1 on 25 March 1980. It set out the information received from Dundalk that all minutes had been passed to D/Supt Courtney at C4, and added:

“This discreet aspect of the investigation was dealt with solely by the Superintendent and perhaps you would contact member direct.”

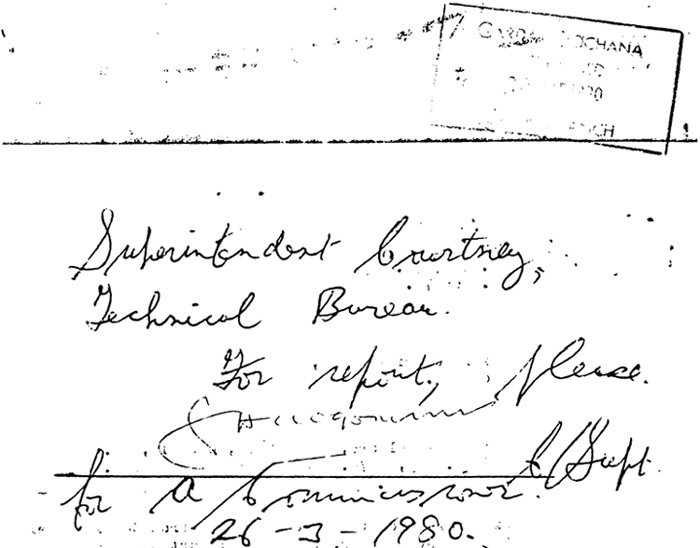

A handwritten note to D/Supt Courtney from the Assistant Commissioner’s office, C1 dated 26 March suggests that this was done.21

This would appear to have been the last written correspondence on the subject. There is no indication of any reply from D/Supt Courtney; the suspects were not interviewed, and the Inquiry has seen no documentation to suggest that the matter was pursued any further. It seems the case lay dormant until 1996, when complaints by the Ludlow-Sharkey family prompted a re-opening of the file, and led eventually to an internal Garda inquiry into why no further progress had been made. This is the focus of the next two chapters.

It is clear that the catalyst for the family’s campaign to learn the full truth concerning the Garda investigation into Seamus Ludlow’s murder was a meeting with investigative journalist Joe Tiernan, which took place in late 1995. According to members of the family, Tiernan had shown up at the Ludlow house some ten years previously. He spoke to James Sharkey’s mother, telling her that he had some information concerning Seamus Ludlow’s murder. She indicated that she was not interested in discussing the subject, and he left.

In October 1995, he returned and asked if he could speak to a member of the family. James Sharkey agreed to meet with him. According to the latter, Tiernan said he had been told by an unnamed Garda officer that the Gardaí knew all along who had killed Seamus. His Garda informant had not given him the names of the suspects, but had said that there were four of them and that they came from Dundonald, Belfast. Eventually in 1998, Tiernan named his Garda source to the family as D/Supt Owen Corrigan.22

Tiernan himself did not believe that loyalists from Belfast would come all that way to kill someone. His own belief was that Seamus Ludlow was killed by members of a loyalist subversive gang from Mid-Ulster, led by Robin ‘The Jackal’ Jackson.

Some months after his contact with the family in October 1995, Joe Tiernan invited the Ludlow-Sharkey family to a meeting organised by him at the Carrickdale Hotel. Also present were a number of other families from Mid-Ulster who had had relatives or family members murdered. Tiernan addressed the meeting and alleged that Robin Jackson and his associates were responsible for those murders. He produced a list of 19 suspects whom he said were part of Jackson’s gang.

Members of the Ludlow-Sharkey family had several more meetings with Tiernan. He encouraged them to hold a press conference and also to write to the Commissioner of An Garda Síochána outlining the information he had given them.

On 2 May 1996 - the twentieth anniversary of Seamus Ludlow’s death - a press conference was held by the family in Buswell’s Hotel, Dublin. A letter was also sent to the then Garda Commissioner Patrick Culligan. In addition to setting out the information received from Joe Tiernan that loyalist subversives were responsible for the killing, a complaint was made that the family “were continually led to understand” by Gardaí investigating the murder that republicans from the North Louth area were responsible for the murder. The full text of the letter was as follows:

“Re: Murder of Seamus Ludlow, Dundalk 1976

Dear Commissioner,

We the Ludlow-Sharkey family, on this the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the death of our beloved brother (and uncle) Seamus Ludlow, who was kidnapped and brutally murdered on 2nd May 1976, write to your to express our concern at the failure of the Gardaí to ever effect a prosecution in this case. We also wish to express our concern at the general conduct of the investigation by the Gardaí at the time, particularly in the light of new information which has subsequently come into our possession.

Following the murder and during the period when Gardaí conducted interviews with members of our family, we were continually led to understand by individual Gardaí, that republicans from the North Louth area were responsible for the murder. We now of course know - from information supplied to us by a number of sources - that this was grossly misleading, and indeed mischievous information and that the murder was in fact carried out by loyalists from Northern Ireland in possible, (but un-proven) collusion with members of the Northern Ireland security forces.

It has further been brought to our attention that the people involved (or some of them) were the same people involved in the slaughter of three members of the Miami Showband less than a year earlier.

This tragic situation, as you can appreciate, has caused great pain and suffering to all members of our family throughout the years, but in particular to those of us who have grown from minors to mature adults, and we are greatly baffled as to why the authorities should do this.

The tragedy and great sense of loss has been further compounded by the fact that Seamus was totally innocent of any wrong-doing and had no connection to any organisation whatsoever.

By reason of the foregoing our family now believes that there is an onus on the authorities- even at this late stage- to put things rights and allow justice to be done.

We should greatly appreciate, therefore, if you as Garda Commissioner could see your way to order a new investigation into the murder with a view to bringing to justice those responsible for this terrible crime. The Ludlow- Sharkey family pledge its full and total co-operation in any such new investigation and undertake to provide the Gardaí with the name of the person believed to be the killer. We should point out however that we understand the Gardaí already possesses this information.

We would also greatly appreciate if you could see your way to meet a delegation from our family to discuss this tragic case in the light of these new developments. We are fully willing to travel to Dublin to attend any such meeting

Finally we wish to courteously inform you that the family, on this sad and sombre anniversary, has decided to avail of the opportunity to highlight some of the disturbing events surrounding this case in the media.

We look forward to hearing from you in anticipation.

Yours sincerely…”

The then Deputy Commissioner of Operations Pat Byrne requested that contact be made with the Ludlow-Sharkey family. This was done, and a meeting was arranged for 16 May at the Ludlow household. An Garda Síochána were represented by D/Supt Michael Finnegan and Supt Michael Staunton. According to James Sharkey, local Sergeant Jim Gannon was also present, though he is not mentioned in D/Supt Finnegan’s report.

James Sharkey handed a list of seven suspects to the Garda officers. He told them the information had come from a journalist (Joe Tiernan), whom he declined to name at that time. D/Supt Finnegan concluded his report as follows:

“If the journalist in question meets us, a further report will follow on the outcome of such meeting.

In the meantime, arrangements have been made with D/Sergeant Brendan McArdle, Ballistics Section, to try and establish if the weapon used in the murder of Seamus Ludlow has since been used in any incident either in the Republic or in Northern Ireland and if so, to see if it can be linked to any particular group or individual.”

On 27 May, James Sharkey contacted Supt Michael Staunton at Dundalk Garda Station to arrange a further meeting at the Ludlow family home on 30 May, at which Joe Tiernan was to be present. The meeting took place as planned, but the journalist did not come.

In a report to the Chief Superintendent, Dundalk dated 26 June 1996, D/Supt Finnegan indicated that further inquiries had revealed the existence of D/Supt Courtney’s report of 15 February 1979. He outlined its contents, stating:

“It contains information which on its face, looks likely to be true. It identifies four suspects for the murder, and gives an in-depth description of the role played by each. However, for some reason which is not set out in the file, it appears that these suspects were never arrested or interviewed about the murder.”

D/Supt Finnegan noted that the four names were not known to the Ludlow-Sharkey family. He then set out what was known of the four suspects’ current whereabouts, and asked for directions as to whether they should be interviewed about the Ludlow murder.

This report was forwarded to Deputy Commissioner Byrne, who on 11 July 1996 directed that a Detective Superintendent from the Criminal Investigation Unit study the file and submit recommendations.

The officer chosen for the task was Detective Superintendent Ted Murphy (later promoted to Chief Superintendent). In the course of his work he interviewed members of the family, and undertook to investigate a number of additional matters raised by them.

A full account of these matters, and the information uncovered by C/Supt Murphy in relation to them, is contained in a later section of this report. The next chapter concerns C/Supt Murphy’s findings in relation to the principal matter at issue – the reason why the four suspects were not interviewed in 1979 or subsequently – and the response of An Garda Síochána to his findings.

Although the information obtained by D/Supt Courtney in 1979 was clearly viewed as more reliable than that given to the Ludlow-Sharkey family by Joe Tiernan in 1996, efforts were made to follow up all possible suspects for the murder. In a report dated 20 January 1997, D/Supt Murphy suggested that the RUC be asked to provide the following information concerning the seven names given by Tiernan:

On 5 February 1997, D/Supt Murphy reported that the RUC had agreed to carry out such enquiries, but that it would take a number of weeks to do so.

The outcome of these enquiries does not appear in the documents seen by the Inquiry, but it is presumed that nothing of any substance emerged to connect those named by Joe Tiernan with the murder of Seamus Ludlow. By the time of a meeting in RUC Headquarters, Belfast on 3 April 1997, the focus was clearly on Hosking, Long, Carroll and Fitzsimmons. D/Supt Murphy reported:

“Present was D/Inspector… who is co-ordinating enquiries. He informed the members that he has traced the four nominated suspects to their present addresses. One of them resides in England.

He has also spoken to the two RUC police officers who obtained the original information concerning the four suspects. One officer has now retired. Both officers are now co-operating with him…

D/Inspector… is satisfied with his progress to date and will communicate any official requests through official channels. He is satisfied that the suspects can be dealt with in his jurisdiction in accordance with the provisions of the Offences Against the Person Act, 1861.23 He will communicate further prior to any action being taken against the four suspects.”

By letter dated 26 June 1997, the RUC sought copies of the investigation report, photographs and ballistic reports from An Garda Síochána. These were provided on 15 September.

On 27 November 1997, D/Supt Murphy attended another meeting at RUC Headquarters. It was reported that provisional dates of 7 and 14 January 1998 had been selected to detain the four suspects:

“Arrests and interviews will be arranged by the RUC and co-ordinated by Det. Inspector... Members from this Unit will be present to provide briefing instructions. In the event of any admissions the Director of Public Prosecutions’ office in Dublin will be consulted to obtain appropriate advices.”

The Inquiry has spoken to Deputy Director Barry Donoghue from the DPP’s office in Dublin, who confirmed that he had a short meeting with D/Supt Ted Murphy at which he was informed of the fact that four suspects were to be arrested in Northern Ireland for the murder of Seamus Ludlow. There was no written correspondence and he did not keep a note of the meeting. He stated:

“I may have telephoned an official in the Northern Ireland DPP’s office to say that we would have no objection to charges being preferred in their jurisdiction if that were to be contemplated. This would have been on the basis of comity between prosecution agencies and on the basis that the Gardaí had no evidence on which they could consider the preferring of charges here. I do not recall any further contact from the Gardaí on this issue.”24

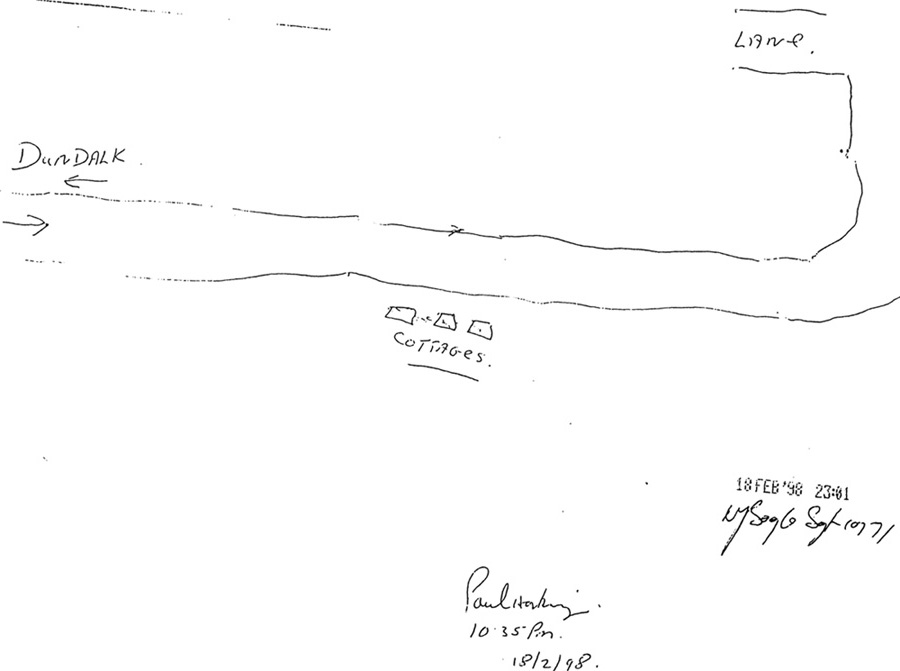

Fitzsimmons, Hosking and Long were eventually arrested by RUC officers on 18 February 1998. On the following day, Samuel Carroll was arrested at his home in England and flown to Belfast. All four men were held at Castlereagh Detention Centre, Belfast and interviewed over a number of days by teams of RUC officers. They were then released without charge.

A number of Garda officers including D/Supt Ted Murphy were present at Castlereagh Detention Centre while the interviews were being carried out. According to D/Supt Murphy, the principal reason for their attendance was in case clarification was required concerning matters within Garda knowledge. In accordance with established protocol, they did not sit in on the interviews themselves, but attended conferences at which progress evaluations and suggestions for lines of questioning were made.25 D/Supt Murphy’s report of 6 March 1998 contained a summary of the information obtained at these interviews. A fuller account was contained in documents submitted by the RUC to the DPP in Northern Ireland for his consideration. These documents were not made available to D/Supt Murphy, but were received by the Inquiry in October 2004 and are considered below.

Prior to the release of the four suspects, the overall facts of the case (including the admissions of Hosking and Fitzsimmons) were discussed with the Director of Public Prosecutions in Northern Ireland. He advised that an investigation file be submitted to him for his directions. D/Supt Murphy has told the Inquiry that he informed the DPP in this jurisdiction that the matter was being pursued by his counterpart in Northern Ireland.

The investigation file was assembled by RUC officers in Belfast. Gardaí gave assistance, supplying documents from the original investigation as requested. D/Supt Murphy’s report concluded:

“[They] and all their colleagues who assisted in the arrests and interviews of the suspects acted in a most professional manner and spared no effort in endeavouring to bring this matter to a successful conclusion. They are to be highly complimented for their efforts and assistance.”

In due course, a letter of appreciation was sent from the Garda Commissioner to the RUC Chief Constable, embodying these sentiments.

The investigation file prepared for the DPP in Northern Ireland and seen by the Inquiry consisted of the following:

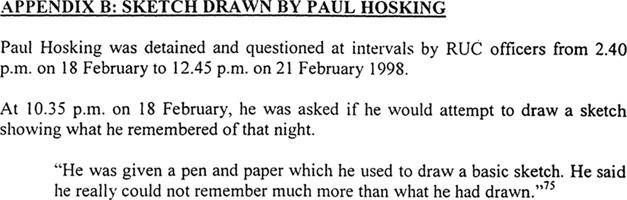

Hosking was interviewed on 12 occasions between 18 and 21 February 1998. His first response was to tell officers that he couldn’t understand why they were talking to him about the Ludow murder, as he had already told Special Branch all he knew about it in 1986 or 1987. When asked was he involved in the murder, he replied:

“I would be a victim of being in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

He then proceeded to give an account of the events of that day, which was noted by the interviewers as follows:

“Hosking then told the following story to us.

‘I used to drink in Comber in the First and Last [pub] and I got to know a team from Belfast who were Red Hand. There was a guy called Dick Long, Mambo, another fellow from Killyleagh who was in the UDR and was a friend of Dick Longs. I got to know these boys over several weeks and then they asked me, I think it was Dick Long, to go with them to the border because there was rumours of IRA roadblocks on the border and they wanted to go down and have a look. I said ok and I went with them…

Me and Mambo and Dick Long and this other man from Killyleagh, we went in this man’s car. It was a sporty job and he was driving. We stopped for a drink in Killyleagh and then drove on to Dundalk and stopped in some pub there, don’t ask me where and then drove on out of Dundalk…

We picked up this man, we gave him a lift because he was thumbing, and then they took him up the road and shot him.26 It was terrible, I have lived with this for years.’

At this point Hosking became upset and appeared shaken.”

When questioned further, Hosking said that Long used to come down to the First and Last pub regularly. He named two others who regularly accompanied him – one of whom, Kenneth Brown, was later convicted with Long of offences relating to the murder of David Spratt.

“He [Hosking] wasn’t drinking buddies with them but occasionally he would have the odd drink with them for 10/15 minutes. He told us he couldn’t be sure but thought they had been coming into the bar for 2/3 months before the night of the ‘disaster’.”

Hosking told them that Carroll (whom he knew only by his nickname, ‘Mambo’) first appeared in the bar about one month before the murder. He was in the company of Long. Contrary to what he said at first, Hosking did not recall seeing Fitzsimmons (the man from Killyleagh) before the night Seamus Ludlow was killed. He was asked if he had ever heard them discussing loyalist paramilitaries. He replied:

“He told us he didn’t but said that everybody in the bar said they were ‘Red Hand Commando paramilitaries’.”

He himself denied any association with the Red Hand Commandos, although he admitted he was a member of the North Down Volunteers (an affiliate of the UDA) at the time.

On the day in question, Hosking had gone to the First and Last bar in the afternoon.

“He said he couldn’t remember fully clearly but recalled that the bar was ‘dead’, near empty. He added the ‘boys’ had gone over for he thought the Rangers / Celtic cup final.”

Long, Fitzsimmons, Carroll, Brown and another man came in around 6 or 7 p.m. He was not sure if they came in together. Hosking said he had about seven pints in the First and Last bar.

At some point, someone suggested that they ‘go for a run’ elsewhere. Hosking, Long, Carroll and Fitzsimmons left together in Fitzsimmon’s car – a yellow, two-door sports model. According to Hosking, Long sat in the back behind the driver’s seat; Hosking sat beside him, and Carroll sat in front. Each time they got into the car that evening, they sat in the same positions.

Hosking told the RUC that they went to a bar in Killyleagh – possibly in a hotel - where he had another 3 or 4 pints, and then drove on to a bar in Omeath. He thought they arrived there around 10.30 p.m. – he remembered watching highlights of the F.A. Cup Final on ‘Match of the Day’.

After leaving Omeath, they drove down to the Border. Hosking thought he remembered them passing through an official checkpoint.

“He [Hosking] didn’t know where but there was a checkpoint, a building with an arm thing across the road. He told us the driver from Killyleagh stopped the car got out and walked over to the building and showed something to a soldier inside it through a window or something. He told us that he remembered vaguely the driver came back to the car and when he got in he was sort of laughing and said something about showing his UDR pass. He added he couldn’t remember what. He told us they all drove to Dundalk and went into a pub. They all had another two or three drinks.”

Hosking remembered seeing a man thumbing a lift as they left Dundalk. He couldn’t say who said to stop, but Fitzsimmons did so, and the man got in the back, between Long and Hosking.