|

|

|

Dáil Éireann An Coiste um Chuntais Phoiblí An Dara Tuarascáil 2005 Tograí le haghaidh athruithe ar an tslí a ndéanann Dáil Éireann Meastacháin i gcomhair caiteachais a bhreithniú Samhain 2005 Dáil Éireann Committee of Public Accounts Second Report 2005 Proposals for alterations in the way that Estimates for expenditure are considered by Dáil Éireann November, 2005 (Prn. A5/1795) ContentsChairman’s Preface Members of the Committee of Public Accounts Orders of Reference of the Committee of Public Accounts The Report Appendix 1. Submission from Deputy Pat Rabbitte. Appendix 2. Report of the PAC visit to the United States Chairman’s PrefaceThis report of the Committee of Public Accounts is firstly concerned with the whole budget or public expenditure cycle of central government – from the formation of the Estimates through to the consideration by the PAC of the Appropriation Accounts and the annual report of the Comptroller and Auditor General. The standpoint is that of the parliamentarian and parliamentary scrutiny of executive action. Secondly, consideration is also given to scrutiny and audit of local government. Thirdly, the Committee recognises the important role that it carries out, on behalf of Dáil Éireann, in examining the way in which money from the Exchequer is spent. However it also acknowledges the lack of proper parliamentary scrutiny of spending Estimates that are allocated to all Government Departments and Offices. In addition, it further acknowledges that the ongoing scrutiny, at a parliamentary level, of major expenditure projects is almost non existent. The Committee, in an attempt to bridge this deficit, appointed Deputy Pat Rabbitte to act as rapporteur on topics one and two above. His report, in full, is included in Appendix 2 of this report. Also, a delegation from the Committee travelled to the United States to study, at first hand, the methods of parliamentary scrutiny in operation both at federal and state levels. The recommendations of the delegation along with the text of their full report are in Appendix 1 of this report. We recommend this report to the Houses of the Oireachtas.

Michael Noonan, T.D., Chairman. November, 2005 Members of the Committee of Public AccountsFIANNA FÁIL

FINE GAEL

LABOUR

GREEN PARTY

SOCIALIST PARTY

1 Deputy Michael Noonan replaced Deputy Padraic McCormack by order of the House on 18th June, 2003. 2 Deputy John Deasy replaced Deputy Paul Connaughton by order of the House on 20th October, 2004. 4 Deputy Michael Smith replaced Deputy Batt O’Keeffe by order of the House on 16th November, 2004. Orders of Reference of the Committee of Public Accounts156.

The ReportCentral Government1. Level of service data in the EstimatesThe P.A.C. agreed that the Estimates volumes and Budget Day documentation should contain information on existing levels of service (ELS) and the full cost of ELS so as to assist Deputies in undertaking output and performance scrutiny and understanding fully what monies are being voted, to what end, to what level of service and what is ‘old’ and ‘new’ money. The Strategy Statements of Departments and State Agencies should include details of output by those organisations in order that activities and outputs can be linked directly to the costs involved. 2. Timing of the whole budget cycle and Budget DayThe major weakness from the point of view of parliamentary scrutiny identified by the PAC is one of timeliness, which is traced back to the timing of the formulation of the annual Estimates and publication of the Book of Estimates. The Committee is of the view that the Estimates formation cycle, the ‘campaign’ including the bilateral negotiations between line Departments and the Department of Finance, should commence much earlier, in perhaps January, and end by the summer. Such an approach would allow for much earlier completion (by early summer) of this phase of the whole budgetary cycle, thus providing the opportunity for bringing forward Budget Day itself and the commencement (and completion) of the ex ante scrutiny process. A timetable, similar to this, is adhered to in the Netherlands and Germany. Such a change would allow for

3. Effective scrutiny of Estimates by Dáil CommitteesA number of options were considered by the Committee as it was agreed that the current method of scrutiny of Estimates by the Select Committees is not effective. Firstly, the idea of allocating additional resources to existing Committees was discounted on the basis that it would be too diffuse and would lack any real impact. Also discounted was the suggestion of establishing a new Budget Committee. The PAC was of the view that such a new committee would duplicate the work of both the existing Committee on Finance and the Public Service and the other sectoral committees. Thus, the PAC propose the following:-

A further development of this service might involve it having the power to request, where necessary, relevant papers and records from Departments. Such initiatives would in all likelihood require primary legislation establishing the office and granting the powers. A consequence of this enhanced role for the Select Committee on Finance and the Public Service would be the opportunity for the other sectoral committees to analyse, in more detail, the level of service being given by the Government Department within their remit. 4. Financial AccountsThe format in which financial information is presented through the annual accounts cycle should conform to best practice and take cognizance of EU and international developments in the setting of standards for financial reporting. The information should be easily accessible and be capable of providing a meaningful basis for review by being presented in a clear and unambiguous manner. While the Committee accepts that a full commercial style accruals based approach may not be the most appropriate for Government Departments and Offices, it does regard the production of a balance sheet as an essential tool for those charged with oversight. Central / Local AccountabilityThe Committee sees a serious gap in the public accountability framework for central government funded moneys administered by local authorities. Under present arrangements there is no accountability to the Committee for the spending of these moneys because the Comptroller and Auditor General is precluded by law from access to local authorities. The Committee recommends that the governing legislation be amended to permit such access and subsequent reporting in order to facilitate scrutiny by the Committee of this important element of Government spending. Any such amendment should provide for value for money aspects to be covered as well as compliance and regularity issues. Apart from addressing the immediate public accountability concern in this regard, the Committee recommends that consideration be given to amalgamating the Local Government Audit Service with the Comptroller and Auditor General’s Office with a view to having a unitary national audit authority examining the spending of all public moneys. Such a move would bring Ireland into line with similar developments in recent years in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales, and with the long-standing practice in New Zealand. Appendix 1PRESENTATION OF ESTIMATES TO DÁIL ÉIREANN –

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

3rd Tuesday in September |

Opening of annual session of Parliament Minister of Finance introduces the budget. |

End September |

General Policy Debate – Plenary Session. |

Early October |

General Budget Policy Debate – Plenary Session. |

Mid-October |

Committees begin scrutinising each budget bill. |

Late October- End-December |

Individual budget bills approved one by one in two-round plenary session. |

1 January |

Start of fiscal year. |

Source: OECD, (OECD, 2002)

4.11 As in Ireland at present there is no specific budget committee in the Dutch Parliament that has overall responsibility for scrutinising the budget in aggregate terms and allocations between different sectors. In practical terms, this means that the aggregate allocation to each sector is taken as a given. While the Parliament does have a special Committee on State Expenditure, it does not discuss the budget. Its responsibility is reserved for general oversight of expenditure management systems, such as the basis of accounting to be applied and the presentation format of the budget documentation. The Committee on State Expenditure has three secretariat staff members – all of whom are specialists in budget related issues. These staff members provide technical advice to the other committees during their examination of each individual budget bill.

4.12 There are 14 sectoral committees in the Dutch Parliament, so most committees will receive one or two budget bills as they are known for scrutiny and will scrutinise the budgets under its mandate. Each committee consists of 25 members with an equal number of alternates. Each committee is assisted by a clerk (most often with a legal background), and by a secretariat staff member specialised in the relevant policy field.

4.13 The examination of the budget normally includes a session at which the minister responds to the committees’ questions. This session is prepared extensively by the staff member serving the sectoral committee and the staff of the Committee on State Expenditure and a report highlighting main points of inquiry will be prepared. Issues for committee members to discuss will often have emerged from the general deliberations and written questions asked of ministers. The minister formally receives notification of the main issues that the committee would like to discuss. Following this session, a report is issued of their discussions with the minister. This is a much more elaborate and considered treatment than one generally finds in Ireland.

4.14 Following the report of the committees, each budget bill is discussed separately in plenary session in two rounds before being approved as law. During the first reading of each budget bill in plenary session, the spokesmen for the different political parties on the committee make detailed comments concerning the contents of the budget and propose amendments, if deemed necessary. Following the contribution of each spokesman, the minister responds.

4.15 The second plenary session follows a few days later. It follows a similar format, although it is more interactive with wider contributions from parliamentarians.

4.16 All of the bills will be passed into law at different times during the session. The first ones will be approved in late October and the last ones in December.

4.17 Traditional governmental budgeting and accounting in Germany is, like our own, input-oriented, cash-based and with an emphasis on legal compliance. Through its Budget Committee, parliament is involved at an early stage (after adoption by the cabinet) in the detailed planning of departmental budgets and grants discharge to the federal government after the end of the fiscal year on submission of the annual statements of account and the audit reports of the federal auditor (the Supreme Audit Institution or SAI, roughly – but not quite – the equivalent of our Comptroller and Auditor General). Parliament is thus involved in the budget cycle from start to finish. As the authority exercising external financial control, the SAI occupies a prominent position and is also involved in all phases of the budget cycle or is informed directly by the Federal Finance Ministry (FMF), unlike the C&AG in Ireland.

4.18 The main features of the German system are that spending is very precisely planned and tight restrictions are imposed on the redirection of expenditure, again somewhat similar to practice in Ireland. Increases in spending are invariably subject to the consent of the FMF. Auditing is conducted by the SAI and is concluded by the granting of discharge by parliament. It is also possible for the German Constitutional Court to enter the frame to adjudicate on issues. The system has shown itself to be effective and no immediate reforms are planned.

4.19 The German budget cycle can be summarized as follows:

December/June: Budget preparation and negations commence very early in the year preceding the budget/financial year (the German budget period operates on a calendar year basis). Negotiations at Ministerial level and the cabinet resolution on the draft budget and financial plan will be completed by the end of June.

August: the draft budget which consists of the federal government’s financial plan (scope and nature of expected revenue and expenditure over a five-year period), the finance report (state of public finances and their probable development) and every two years the subsidies report (financial aid survey) together with the budget bill is presented to parliament.

September: after the first parliamentary reading, the draft budget is referred to the Budget Committee, which takes charge of the subsequent deliberations. The Committee scrutinises all the estimates and, where necessary, submits proposals for amendment. The work of the Budget Committee is divided between specialized committees dealing with each departmental budget. Discussions are held with representatives of the supreme federal authorities concerned, the FMF and the SAI.

November: Issues that cannot be finally disposed of when the departmental budgets are considered by the Budget Committee are deferred until final sessions (of which there are generally two). The FMF submits documentation for decisions to be taken in the final sessions combining all the deferred issues and other matters on which it considers a decision necessary. This is followed by the second and third readings of the draft budget in parliament, during which minor amendments are made.

December: the final debate is held in the parliament and the budget statute is promulgated.

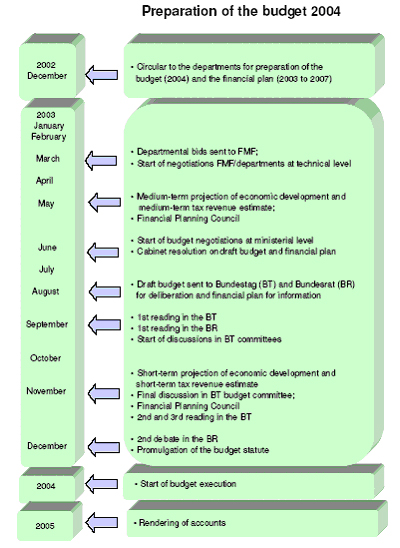

The following diagram, taken from a Federal Finance Ministry paper, shows the process for the formation of the 2004 budget.

Source: Federal Ministry of Finance (FMF, 2004)

4.20 The Dutch and German systems are characterised by a much earlier start to their equivalent of our Estimates formation phase with the phase of parliamentary scrutiny also commencing earlier. Parliamentary scrutiny also appears much more detailed than in Ireland with parliamentarians having extensive technical and professional support. Why can’t we do it? Or maybe why don’t we do it?

4.21 We have in Ireland recently implemented finally the 3-year rolling envelope approach to public finance planning, capital and current (if not grant of supply and appropriation): on Budget Day the Department does publish not simply the Budget Day changes but also in effect preliminary Estimates for the following two years – again subject to the usual Finance caveat on NPC although the contention of this submission, already made, is that this caveat is itself pretty murky territory.

4.22 However the point of this submission is not so much murkiness of the concept of NPC as the existence now of a rolling three-year multi annual framework for the whole budget cycle – with the publication of data on receipts (tax and non-tax) and expenditure (current and capital) and gross spending projections by Ministerial Vote Group. There is in all of this a real basis for bringing forward the timing of the whole budgetary process and making more timely the process of parliamentary scrutiny.

Proposal

One option, which I would support, would be to recommend that the Estimates formation cycle, the ‘campaign’, commence much earlier, in January (as in the Netherlands and Germany).

Such an approach would allow for much earlier completion (by early summer) of this phase of the whole budgetary cycle, thus providing the opportunity for bringing forward Budget Day itself and the commencement (and completion) of the ex ante scrutiny process – again as in the Netherlands and Germany.

Such a change would allow for:

4.23 Should there be a single, ‘super’ Budget Committee as in Germany and also New Zealand (see below)? I have no definitive viewpoint on this question at this stage, although some consideration might be given to enhancing or enlarging the role of the Finance Committee. What is more important in my view in the first instance is the professional and expert resourcing of the present system from the point of view of the task of parliamentary scrutiny. One model here is obviously that of the United States with its powerful Congressional Budget Office (CBO) servicing the Budget Committees of the House and the Senate. The view of this submission is that the resourcing of committees (a research service) is now a critical issue but that the elaborate CBO model is perhaps not in our case the way forward: the CBO is after all foremost a counterweight to the (President’s) Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and is something that is critically related to the unique constitutional arrangements adopted by the US, the pure separation of powers combined with a distinctly precautionary attitude in the constitution and by the legislative arm to the executive power of the state.

4.24 It is generally recognised that professional support for parliamentarians is weak in Ireland compared to other parliamentary systems. The annual report for 2004 of the Houses of the Oireachtas Commission contains the following passage under the heading “Research services for Members” –

The [International Benchmarking Review] IBR report found that there was a clear case for the improvement of the library and research service available to the Houses of the Oireachtas and its committees.

A key recommendation of the IBR study was the establishment of a dedicated research service within the Office for use by all Members of the Houses of the Oireachtas on an equal basis. Research services available to Members of the Houses have been extremely limited over the years and the report confirmed the long-standing view that the Irish Parliament did not at all measure up internationally in terms of resources dedicated to this area.

The Commission considers that access to a professional research service is a basic necessity for any member of a modern parliament. The consultants recommended the establishment of a service comprising up to 22 researchers headed by a Head of Library and Research at senior management level and grouped according to subject specialisms.

The Commission established a subcommittee to consider the consultants’ recommendations, together with the Office Management’s policy proposal on the matter. The sub-committee held a number of meetings, including a very useful presentation by two senior officials from the Australian Parliament’s Library Research Service who were in Ireland on a private visit. The Commission decided in December 2004 to proceed as follows:

The Commission considers that an Oireachtas Research Service will greatly improve Members’ ability to hold Government to account, by providing much needed information resources to counter the vast civil service resources, which are at the disposal of Members of Government and Ministers of State.

4.25 This submission endorses the Commission’s plans for the development of a parliamentary research service within the Library of the Oireachtas but would also go further, as outlined below.

Proposal

This submission is strongly of the view that the Committee should communicate to the Oireachtas Commission its opinion that some number of the 11 specialist research staff proposed to be recruited should be dedicated exclusively to providing high level support and research to the select committee system in respect of the consideration of the Estimates – initial and supplementary. Recruitment should also be in place in time for the next Estimates cycle.

Consideration should also be given to this support service having a professional head of service, separate from the envisioned head of research, something akin in status and authority to the Comptroller and Auditor General and his role in respect of ex post scrutiny carried out by this Committee. The service might also have power to request where necessary, relevant papers and records from departments. A period of time operating on a non-statutory basis might assist in assessing whether the system required primary legislation establishing the office and granting the powers.

It might also be appropriate for the Finance and Public Service Committee or the PAC to scrutinise the quarterly Exchequer Statement.

4.26 One issue that has generated intense debate in Ireland and elsewhere in recent years as regards the public financial accounts whether in respect of spending or income is that of appropriate accounting principles. Generally public financial accounts are in most countries prepared on a cash basis while those of private commercial undertakings and many public undertakings that stand at arms length from government departments are prepared on an accruals and consolidated basis and in conformity with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) set out by the various national professional accounting institutes and the international accounting standards bodies. Our local authorities are also currently moving to accrual accounting including drawing up balance sheets.

4.27 Accrual accounting, proper consolidation and the preparation of accounts according to (national) GAAP principles is widely seen as superior to the cash-based approach traditionally used in government. Mention is made of the insistence by capital markets, stock markets and indeed regulatory public authorities that publicly quoted companies prepare their financial statements and accounts on this basis. Cash based accounting it is argued allows for opportunities for “cooking the books” (McCarthy, 2002) although the Enron story and similar financial scandals of recent years shows that cash-based accounting is not alone in this regard and there are different versions of GAAP in different jurisdictions.

4.28 Accrual accounting is distinguished from cash accounting by reporting revenues and expenditure as they arise (occur) and not when the cash receipt/payment is made. There are two main advantages cited for adopting accrual accounting in the public sector. The first is that it discloses the true cost of government, for example employee pensions are accounted for in a cash system when the payment is made to the pensioner rather than when the individual earned that pension over the course of his or her service. The second benefit is to improve decision-making in government by using this enhanced information. In such an environment it is expected that managers should be responsible for all costs associated with the outcomes and/or outputs produced, not just the immediate cash outlays. Only accruals allows for the capture of these full costs, thereby supporting effective and efficient decision-making by managers. In short, where managers are given flexibility to manage their own resources (inputs), they need to have the necessary information to do this.

4.29 As a consequence, the adoption of accrual accounting by governments can increase transparency and accountability by making the stewardship role more robust, for example financial reporting for assets may highlight failures to properly manage resources such as the collection of debts: again the issue of levels of service. It must be borne in mind that financial reporting in the Irish public sector is based on distinct legal entities which are individually accountable to Dáil Éireann and therefore accountability and issues of consolidation would require to be aligned to this framework were it to be adopted.

4.30 A distinction must be made between accrual budgeting and accrual financial reporting although the tendency is for accrual budgeting to follow accrual accounting where it has been adopted by government (e.g. the UK and New Zealand). The OECD in a 2003 (OECD, 2003) commentary on this issue in the public sector stated that

“there is much greater acceptance of accruals for financial reporting than for budgeting purposes. This does not appear to be a temporary snapshot as countries migrate to accrual budgeting but rather a firm view among a number of member countries. Two reasons are most often cited for this. First, an accrual budget is believed to risk budget discipline. The political decision to spend money should be matched with when it is reported in the budget. Only cash provides for that. If major capital projects, for example, could be voted on with only the commensurate depreciation expense being reported, there is a fear that this would increase expenditures for such projects. Second, and somewhat contradictory to the first reason, legislatures have often shown resistance to the adoption of accrual budgeting. This resistance is often due to the sheer complexity of accruals. In this context, it is noteworthy that the legislatures in those countries that have adopted accrual budgeting generally have a relatively weak role in the budget process.”

4.31 The difficulty with applying accruals to financial reporting only and not to the budget is that it could lead to a mismatch in the decision process between the allocation of resources and accounting for their use. The budget is the key management document in the public sector and accountability is based on implementing the budget as approved by the legislature. If the budget is on a cash basis that is going to be the dominant basis on which the legislature and heads of departments work. Financial reporting on a different basis risks becoming a purely technical accounting exercise in these cases.

4.32 Notwithstanding these and other concerns, for example in respect of resource implications, the need to train civil servants to operate accrual accounting and so on, more and more countries are adopting accruals for their financial reporting (Hepworth, 2003, 2004a). This typically proceeds with individual ministries and agencies first adopting accruals for their own reporting. Over time, more and more ministries and agencies adopt accruals, and then the financial statements for the whole-of-government are presented on an accrued basis. In this context it is worth repeating that the majority of the Irish State expenditure is reported on an accruals basis (non-commercial State bodies, health sector, third level, etc) whereas the annual budgetary process is performed on a cash basis. The accounts of government departments are prepared on a cash basis with, increasingly, additional accrual-type information reported. The consolidated accounts of the Exchequer (the Finance Accounts) are prepared on a cash basis together with certain accrual-type information for example the National Debt Statement. Under the Strategic Management Initiative and the Management Information Framework both accrual budgeting and accounting for central government are being reviewed with a view to ensuring that appropriate information is available for decision makers and parliamentary scrutiny.

4.33 The accounting standards issue is clearly connected with the theme of administrative reform – how the public service and the public sector are managed and go about their business. In essence as the argument goes, if there is to be a primary emphasis on output or performance budgeting that will only be achieved by a switch to accrual accounting – or in the alternative, the adoption of accrual will facilitate the adoption of a performance or output approach to public spending, including in respect of parliamentary scrutiny of performance.

4.34 Public sector reforms and initiatives in the UK, which have also been mirrored to some extent in Ireland, have arisen due to pressures such as increased demands on public services and the need to ensure value for money (Hepworth 2004b). The UK has moved at a somewhat greater speed in reforming its financial framework in that it has developed at the central government level an accrual model for accounting and budgeting (referred to as resource accounting).

4.35 The UK move to accrual accounting for central government has only occurred towards the end of the very long process of public sector reform and was an essential feature to ensure that comprehensive and reliable information was available to decision-makers.

4.36 Resource Accounting and Budgeting (RAB) is a system of planning, controlling and reporting on public spending for the UK government. It is the application of accruals accounting for reporting on the expenditure of central government and a framework for analysing expenditure by departmental aim and objectives, relating these to outputs (deliverables) where possible. Resource budgeting covers planning and controlling public expenditure on a resource accounting basis. RAB was launched in 1993 and the first resource accounts were published for the UK financial year 2001- 02.

4.37 The UK government recommended that the framework of accounting principles and conventions for resource accounting in departments should be based on UK GAAP, in particular the accounting and disclosure requirements of company law and accounting standards, adapted to meet the particular requirements of central government and parliamentary control. The aim was to ensure broad consistency with accounting practice in the rest of the public sector and the private sector. It was further proposed that one consolidated set of resource accounts should be prepared by each department. This would include the assets and liabilities of its executive agencies including Trading Funds.

4.38 While accounts are prepared in accordance with UK GAAP, a Financial Reporting Advisory Board was established to help to ensure that any adaptations of, or departures from, UK GAAP for the public sector are justified and properly explained. The Board acts as an independent review in the process of setting accounting standards for government during the development of resource accounting and the UK Treasury must consult with it on financial reporting principles and standards.

4.39 The UK Treasury states (www.hm-treasury.gov.uk) that resource budgeting supports the Government’s agenda for high quality public services by delivering:

4.40 New Zealand is among a small number of countries (e.g. also United States, Canada, United Kingdom) that have been to the forefront in changing the budgetary information and structure for State expenditure, and have shifted their estimates and appropriations process away from a focus solely on inputs (costs) to encompass outputs (deliverables). This entailed a move from cash-based accounts and budgeting to an accruals basis for both government accounting and the budget cycle). The most recent enactment in the reform programme is the Public Finance (State Sector Management) Bill 2004.

4.41 The Bill gives statutory effect to recent improvements in the budget documents and, in particular, the Statements of Intent (that document the result of “Managing for Outcomes” planning) now prepared by departments and Crown entities (the New Zealand equivalent to non-civil service public entities).

4.42 Earlier legislative reforms simply required forecast financial statements, which were initially delivered in a single bound book, and then, from the early nineties, through departmental forecast reports.

4.43 The Bill effectively acknowledges the improvement of standards in this area, and moves the minimum standard marker. It requires the Statement of Intent to include information on the nature and scope of a department’s functions and operations; the specific impacts, outcomes, or objectives that the department seeks to achieve; how the department intends to perform to achieve those impacts, outcomes, or objectives within a changeable operating environment; and the main measures and standards that the department intends to use to assess itself: echoes here again of the concept of transparent service levels.

4.44 In the words of John Whitehead, current Secretary of the Treasury in New Zealand, “This is quite a move from those early financial statements and it formally reflects the public service’s “reason for being”, if you like. It highlights the reasons for believing that the operations of departments will make a difference for New Zealanders. These formal reports are the external expression of the outcomes-focused management processes that departments undertake. Again, the extent they are successful rests largely in the hands of departments, Crown entities and the management processes in these organisations. However, the new reporting means that departmental performance – or the lack of it – will become more transparent.”

4.45 In New Zealand the Budget provides the overall mechanism through which the Government reallocates existing resources and provides a limited amount of new resources, in order to achieve its desired outcomes within its fiscal policy objectives. The Budget represents a culmination of Government decisions about:

4.46 The Government’s Budget in any one year is the key outcome of a cycle of activity that occurs throughout the year (in fact, each year deals with 3 Budgets – current, future and past). This cycle comprises a range of products and processes which feed into and flow from the Budget. The Budget Package, once agreed by Government, needs to be approved by Parliament.

4.47 The legislative framework is generally comparable to Ireland in that public money cannot be spent without the prior approval of Parliament and the formal authority for most expenditure is provided via an ‘appropriation act’ which authorises departments to incur expenses up to a certain limit for a specified purpose. The Minister will table the ‘Estimates’ on Budget Day in parliament. The Estimates contain the Government’s request for appropriations, and supporting information (Fiscal Strategy Report, departmental Statements of Intent and the Budget Economic and Fiscal Update).

4.48 The Estimates contain a number of principal parts for each Vote among which are:

4.49 Following the Budget speech in late May (New Zealand operates on a July to June financial year) the Appropriation Bill is referred to the Finance and Expenditure select committee, which, under Parliament’s Standing Orders has two months to conduct its examination and report back to the House (the New Zealand parliament is unicameral). The Finance and Expenditure committee may examine a Vote itself or refer it to any other committee for examination. Under Standing Orders, Parliament has three months from its introduction to pass the Appropriation Bill (this includes the Finance and Expenditure select committee phase).

4.50 Because expenses and capital expenditure cannot be incurred without parliamentary authorisation, and because there is often a time lag between new spending happening and the passing of an Appropriation Act, parliamentary authority to incur expenses or capital expenditure in advance of an appropriation is often needed. Imprest Supply Acts fulfil this requirement and are normally passed twice a year, the first one at the start of the financial year.

4.51 New Zealand has introduced recent legislative changes in order to enhance the overall fiscal management of State’s financial performance and position. These enhancements will provide better information to Parliament though Ministers will have more flexibility in managing the monies voted to their portfolios. Reporting by departments will also be amended to show a broader range of information about intended and actual performance (financial and non-financial). These enhancements build upon the existing process which ensures accountability and transparency for the budget preparation cycle though a number of required annual financial reports, the key ones being:

4.52 Some commentators refer to the Netherlands and Germany as part of the Continental European model of budgeting and accounting for government expenditure. They have broadly similar public administration structures in that government operates at three levels, the national or federal government, provincial/state governments and local level. Their approach to reform of the whole budgetary cycle though is rather different.

4.53 At central government level both countries apply what is called modified cash accounting12 which generally combines cash and commitment accounting (e.g. authorisation to incur expenditure that lead to payments in future years). Accrual accounting becomes more evident at the more localised or peripheral levels of government for example

4.54 Reform projects and initiatives have commenced in both countries but at a different pace. As in other jurisdictions the focus has been to give a wider consideration in the budget process to outputs (deliverables), producing a more result-directed approach of business management within government. In 2000, the Dutch Minister of Finance announced that steps towards accrual accounting for central government would be taken gradually. It was decided to start a program directed at the improvement of financial management before the general transfer to accrual accounting. Accrual accounting would be initially introduced for parts of departments but not agencies, which do not execute core government tasks. Introduction for central government as a whole would be the next step. It is expected that this transitional process will last until 2006.

4.55 In Germany however, governmental budgeting and accounting continues to be input-oriented, cash-based, compliance-oriented and exclusively aimed to meet the budgetary control needs of the legislature. The OECD commented in 2004 (OECD, 2004) that “The present German budgeting system places little emphasis on policy outcomes. Legislation focuses on parliamentary control of inputs as opposed to budgetary appropriations on a programme or activity basis. German legislation requires that budgeting is based on the cash rather than the accruals principle. While some moves were made by states and communities to introduce elements of accruals accounting, against the standard required by legislation these efforts are supplementary accounting practices and therefore unlikely to be adopted on a general scale within the present legal system.”

Observation

The question of cash v accruals accounting is perhaps something of a side issue in this context of parliamentary scrutiny. Personally, I agree with those who favour some sort of modified cash accounting – In fact it is argued by professional accountants that the provision of cashflow information and the limitations imposed on “speculative” accruals in GAAP actually means that the corporate world is really using something similar. I do, however, strongly believe that where appropriate, the balance sheet is an essential tool for those charged with oversight including parliamentary oversight and scrutiny – a good accounting system must recognise the financial consequences of events that have already taken place as a closing liability (even if the bill hasn’t yet been received). I would say that three things are important when considering the issue;

“Every local authority is accountable for its stewardship of the public funds committed to its charge. Stewardship of public funds is a function of management. It is discharged by the establishment of sound financial control systems and the publication of audited financial statements.”

Local Government Audit Service

Report 2001/2002

5.1 The local government system is the forum for the democratic representation of local communities and for associated decision-making at local level and provides an opportunity for people, through their representatives, to influence the economic, social and cultural policies affecting their areas. Its importance is underlined by the recent constitutional amendment. Local government delivers a range of essential public services to communities throughout the country. The Department of the Environment and Local Government has a role in supporting and strengthening local government’s capacity to provide these services to the highest possible standards.

5.2 The funding to local authorities for these services is provided mainly by the Exchequer through general taxation and EU structural funds for major capital infrastructure projects, motor vehicle taxation and local charges such as rates and service charges. Local authority expenditure including the capital programme amounted to over €6,000 million in 2002.

5.3 Exchequer and EU financing provided over half of this expenditure in 2002 and these funds are normally channelled through various accounting frameworks: Appropriations by Dáil Éireann, the most significant of which is to the Vote for Environment and Local Government the Local Government Fund which is administered by the Department of the Environment and Local Government; and in some instances State agencies further coordinate the planning and financing of services for example the National Roads Authority which oversees major national road projects.

5.4 Each level of financing from EU, to central government (including State agency) and through to the local authorities who will ultimately deliver the services or directly incur the expenditures, brings with it the responsibility for the proper control and management of resources and ultimately public accountability. This accountability is discharged in a number of ways for example the accountability for voted monies and other funds by department Accounting Officers to the Public Accounts Committee.

5.5 Recent legislation and other reforms have attempted to strengthen this framework at the local and departmental level. A new Code of Accounting Practice together with the introduction of new financial management systems are apposite in this respect. In addition the Department of Local Government and the Environment is carrying out an independent review of the local government funding system, including efficiency and accountability issues.

5.6 Among the key principles for ensuring that public accountability is properly discharged is the timeliness of the assurance provided and the nature of that assurance relative to the respective accountability of the bodies concerned.

5.7 The financial and audit procedures of local authorities are at present governed by Part 12 of the Local Government Act 2001. LGAs are independent in the performance of their professional functions. They currently audit a total of 207 bodies including city, town and county councils, regional authorities and motor taxation offices. The service at present has a staff complement of twenty-five LGAs and ten assistant auditors. Specific audits are assigned to LGAs, under warrant, issued by the head of the service, the Director of Audit. The total staff compliment at present is thirty-five people with a number of vacancies also in the service. This is a relatively small staff compliment undertaking external audit of the financial statements of 207 local government bodies.

5.8 Two difficulties have arisen in these areas.

5.9 The first issue relates to the timing of the provision of audit assurance by the Local Government Audit Service, LGAS, on the financial statements of local authorities and referred to as audit lag. Audit lag can arise for a variety of reasons including staff shortages, the legal formalities involved in the commencement of the audits and the time lag between the end of the financial year and the finalisation of the draft accounts of local authorities. The latest report of the LGAS (for the year 2001/2002) outlines the significant progress made in reducing the number of audits in arrears at 31 March 2002.

5.10 Local authorities are required to prepare their financial statements in accordance with this Code. The code and Article 9 of the Public Bodies Order, 1946 require that the annual financial statement of a local authority should be prepared and considered by it within the following 12 weeks. Councils may also form audit committees to consider the accounts. The financial statements of local authorities are audited by the Local Government Auditors (LGAs) of the LGAS who are appointed by the Minister for the Environment, Heritage and Local Government. They provide independent professional scrutiny and audit of the financial and regularity stewardship of local authorities and inform the public of the results of such review.

5.11 However the view of this submission is that the time taken to finalise and have audited the annual accounts of local authorities and related bodies is by any standard unacceptably protracted, making a mockery of any concept of timeliness as a standard for audit practice. For example at 31 March 2002 due to delays in finalising accounts and objections to matters contained in accounts the 1998, 1999 and 2000 audits for Wicklow County Council and New Ross UDC were not completed. Further, 23 audits in the 2001/2002 audit cycle (audits of accounts for 2000) were still in progress and 14 had not yet commenced (LGAS, 2002). I am inclined to put the extended audit cycle down to short staffing at the LGAS.

5.12 At the level of the local authorities clearly the financial function has had low priority and status although this is changing: for example there has been a drive to recruit 40 professionally qualified financial/management accountants and a new computerised, integrated financial management system (Agresso) funded by the Department is being deployed through the local government system. Full accrual accounting is also being adopted, supposedly by December 2003.

5.13 At central government level (the Department) the local government audit function is clearly something of a poor relation – even with some increase in the staff compliment in recent years.

Proposal

Having regard to the figures involved, the lack of timely information and audit lag issues there is a strong case for the Committee either

or

5.14 The second issue in respect of local authority expenditure and audit refers to a gap in the accountability arrangements to Dáil Éireann for expenditure administered by local authorities but funded by Oireachtas grants – in particular, the capital programme for local government which is mainly financed through the Exchequer. The audit undertaken by LGAS does not feed into the Dáil accountability process (as embodied by the Public Accounts Committee). It is therefore difficult for the funding approval organ viz. Dáil Éireann to satisfy itself that the money provided is being properly used and is achieving value for money. The formula implicit in the Comptroller and Auditor General (Amendment) Act 1993 whereby improved liaison between the C&AG and the LGAS could address the problems has proven to be a totally inadequate substitute.

5.15 By section 8 of the Act, the Comptroller may “inspect” the accounts, books and other records of any person in receipt of public moneys if the amount received constitutes not less than 50 per cent of the gross receipts of the person in that year. An inspection is not a full audit and is done for the purpose of determining whether and to what extent –

5.16 However, local authorities are listed in the Second Schedule to the 1993 Act as bodies that are specifically excluded from the ambit of section 8 of that Act, which governs the Comptroller’s power to inspect. The result is that, not only are local authorities not audit clients, neither are they within the ambit of the power of inspection. Having regard to the fact that well over €4.45bn (estimate for 2000) is spent by local authorities on the current and capital sides each year, of which a very significant percentage comes from persons whose accounts are audited by the Comptroller (for example the Department and the National Roads Authority), this represents a significant restriction in the Comptroller’s capacity to account for a significant portion of national public expenditure.

5.17 The restriction on the Comptroller’s capacity to account for the expenditure of these sums might not be of concern if local audit was an adequate substitute. However it is not. This is not a criticism of the professional adequacy and competence of the Local Government Audit Service. What is of concern is the lack of any coherent, systematic or sustained response by local authority members to the statements and reports of that service. Put simply and starkly, I am not convinced that local authority audit committees function in any meaningful sense, as a means of ensuring accountability for the stewardship of public funds.

Proposal

The Committee might consider in that context section 21 of the Comptroller and Auditor General (Amendment) Act 1993. That section permits the Minister for Finance by order to amend the Second Schedule, which lists the bodies, including local authorities, excluded from the application of section 8 and so exempt from inspection by the Comptroller in respect of moneys received from central government.

Two caveats should be entered, however. The first is that an amendment to the Second Schedule would permit an inspection by the Comptroller of the accounts of a particular local authority only if the aggregate of the amounts received by that authority, directly or indirectly, from a Minister or from the Central Fund constitutes not less than 50 per cent of the gross receipts of that authority. In other words, even if local authorities were “inspectable” as a class, a particular authority whose own income was not less than 50 per cent of its total would not be liable to inspection.

This would exempt certain local bodies which generate more than 50 per cent of their income from commercial rates and service charges.

The Committee might therefore wish to propose an amendment to the 1993 Act so as to include all local authorities within the category of bodies whose accounts are capable of being inspected by the Comptroller and Auditor General, regardless of the proportion of their income coming from central resources.

Second, a right of inspection would enable the Comptroller to inspect whether moneys received from central government was spent “in accordance with any conditions specified in relation to such expenditure”. He could therefore inspect compliance with criteria relating to economy and efficiency only to the extent that such conditions were in fact specified by the body from which the moneys were issued.

The Committee might wish to consider whether this creates a potential loophole in the inspection regime and, if so, whether it should be plugged by legislative amendment.

This is a submission to the Committee of Public Accounts (PAC)

This submission is concerned with the whole budget or public expenditure cycle of central government – from the formation of the Estimates through to the consideration by the PAC of the Appropriation Accounts and the annual report of the Comptroller and Auditor General. The standpoint is that of the parliamentarian and parliamentary scrutiny of executive action.

Some consideration is also given to scrutiny and audit of local government.

A number of proposals are advanced for consideration by the Committee.

1. Level of service data in the Estimates

It is my submission that the Estimates volumes and Budget Day documentation should contain information on existing levels of service (ELS) and the full cost of ELS so as to assist Deputies in undertaking output and performance scrutiny and understanding fully what monies are being voted, to what end, to what level of service and what is ‘old’ and ‘new’ money.

2. Timing of the whole budget cycle and Budget Day

The major weakness from the point of view of parliamentary scrutiny identified in this submission is one of timeliness, which is traced back to the timing of the formulation of the annual Estimates and publication of the Book of Estimates.

This submission recommends that the Estimates formation cycle, the ‘campaign’ including the bilateral negotiations between line departments and the department of finance, commence much earlier, in perhaps January, and end by the summer (as in the Netherlands and Germany).

Such an approach would allow for much earlier completion (by early summer) of this phase of the whole budgetary cycle, thus providing the opportunity for bringing forward Budget Day itself and the commencement (and completion) of the ex ante scrutiny process – again as in the Netherlands and Germany.

Such a change would allow for

3. A new committee system to consider the Estimates?

I have at present no fixed view as to whether the present committee system should be replaced for the purposes of the consideration of the Estimates by a single Budget Committee as is the case in some other countries although some consideration might be given to an expanded role for the Finance and Public Services Committee, for example in relation to scrutiny of the quarterly Exchequer returns.

4. A parliamentary research service

This submission is strongly of the view that the Committee should communicate to the Oireachtas Commission its opinion that some number of the 11 specialist research staff proposed to be recruited should be dedicated exclusively to providing high level support and research to the select committee system in respect of the consideration of the Estimates – initial and supplementary. The service should be established and recruitment of expert staff completed in time for the next Estimates.

Consideration should also be given to this support service having a professional head of service, separate from the envisioned head of research, something akin in status and authority to the Comptroller and Auditor General and his role in respect of ex post scrutiny carried out by this Committee. The service might also have power to request where necessary, relevant papers and records from departments. Such initiatives would in all likelihood require primary legislation establishing the office and granting the powers.

Accounting principles

Issues of accounting principles – cash v accruals, the use of balance sheets and consolidation – have been much debated in Ireland and internationally. The question of cash v accruals accounting is perhaps something of a side issue in this context. Personally, I agree with those who favour some sort of modified cash accounting – in fact it is argued by professional accountants that the provision of cash flow information and the limitations imposed on “speculative” accruals in GAAP actually means that the corporate world is really using something similar. I do, however, strongly believe that the balance sheet is an essential tool for those charged with oversight – a good accounting system must recognise the financial consequences of events that have already taken place as a closing liability (even if the bill hasn’t yet been received – again, the Nursing Homes issue is a good example). I would say that three things are important when considering the issue;

Having regard to the figures involved, the lack of timely information and audit lag issues there is a strong case for the Committee either

or

The Committee might consider in that context section 21 of the Comptroller and Auditor General (Amendment) Act 1993. That section permits the Minister for Finance by order to amend the Second Schedule, which lists the bodies, including local authorities, excluded from the application of section 8 and so exempt from inspection by the Comptroller in respect of moneys received from central government.

Two caveats should be entered, however. The first is that an amendment to the Second Schedule would permit an inspection by the Comptroller of the accounts of a particular local authority only if the aggregate of the amounts received by that authority, directly or indirectly, from a Minister or from the Central Fund constitutes

not less than 50 per cent of the gross receipts of that authority. In other words, even if local authorities were “inspectable” as a class, a particular authority whose own income was more than 50 per cent of its total would not be liable for inspection.

This would exempt some local authorities which generates more than 50 per cent of their income from commercial rates and service charges.

The Committee might therefore wish to propose an amendment to the 1993 Act so as to include all local authorities within the category of bodies whose accounts are capable of being inspected by the Comptroller and Auditor General, regardless of the proportion of their income coming from central resources.

Second, a right of inspection would enable the Comptroller to inspect whether moneys received from central government was spent “in accordance with any conditions specified in relation to such expenditure”. He could therefore inspect compliance with criteria relating to economy and efficiency only to the extent that such conditions were in fact specified by the body from which the monies issued.

The Committee might wish to consider whether this creates a potential loophole in the inspection regime and if so, whether it should be plugged by legislative amendment.

References

Buchanan, James M (1973), The Public Finances. An Introductory Textbook. (3rd edition). Richard D Irwin Inc.

Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (2001), Ensuring Accountability in Public Expenditure. Report of a CPA workshop held in Nairobi in 2001. [Included at Appendix 1]

Department of Finance, Public Financial Procedures.

Federal Ministry of Finance (FMF) (2004), Accountability and Control, Federal Republic of Germany. [Included at Appendix 4]

Hepworth, Noel (2003), Preconditions for successful Implementation of Accrual Accounting in Central Government. Public Money and Management, January 2003. [Included at Appendix 6] http://www.cipfa.org.uk/international/presentations.cfm

Hepworth, Noel (2004a), Accrual accounting in the Public Sector, Euromed Conference, Ankara, November 2004 (Slide presentation) http://www.cipfa.org.uk/international/presentations.cfm

Hepworth, Noel (2004b), Budget, accounting, control systems - the UK example, Formez seminar, Naples, November 2004 (Powerpoint presentation) http://www.cipfa.org.uk/international/presentations.cfm

McCarthy, Colm (2002), Generally Unacceptable Accounting Principles: The Irish Public Finance Accounts. Quarterly Economic Commentary, ESRI, Summer 2002. [Included at Appendix 5]

OECD (2002), Budgeting in the Netherlands by Allen Schick, in Journal on Budgeting, Vol.1, No. 1, March 2002.

OECD (2003), Accrual Accounting and Budgeting: Key Issues and Recent Developments by Jón R. Blöndal, in Journal on Budgeting, Vol.3, No. 1, March 2002.

OECD (2004), OECD Economic Survey of Germany 2004.

O’Toole, Larry (1997), Anatomy of the Expenditure Budget. SIGMA Policy Brief No. 1. [Included at Appendix 2]

Table

Select Committee consideration of the revised 2005 Estimates

Select Committee |

Vote(s) |

Amount |

Date(s) |

Days |

Time |

Remarks |

|

Finance and Public Service |

Finance Group Votes 1, 5, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18 |

€1.34bn |

30 March 2005 |

1 |

3h45min |

Finance Group Votes cover a range of entities and offices apart from the Department proper. They include the President’s Establishment, the C&AG, Revenue, OPW etc. |

|

Finance and Public Service |

Taoiseach’s Group Votes 2, 3, 4, 13, 14 |

€180.2m |

20 April 2005 |

1 |

1h40min |

Taoiseach Group Votes include the Department and a number of offices such as the CSO, the Chief State Solicitor’s Office and the office of the DPP. |

|

Health and Children |

Votes 39, 40 |

€11.9bn (Gross) |

5 May 2005 |

1 |

2h10min |

The second biggest spending department. The allocation is divided between two Votes – the Department proper and second, the new Health Services Executive (HSE) (Vote 40). |

|

Foreign Affairs |

28, 29 |

€699m |

14 June 2005 |

1 |

3h10min |

||

Arts, Sport, Tourism, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs |

33, 35, 24 |

€849.6 |

25 May |

1 |

3h55min |

||

Social and Family Affairs |

Vote 38 |

€12.2bn |

14 June 2005 |

1 |

2h25min |

Biggest spending department in the state. |

|

Transport |

Vote 32 |

€2.1bn |

15 June 2005 |

1 |

1h48min |

||

Education |

Vote 26 |

25 May 2005 |

1 |

1h45min |

|||

Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights |

36, 37 (Defence Votes) |

€934m |

24 May 2005 |

1 |

1h |

||

Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights |

19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Justice Group |

€2bn |

18 May 2005 |

1 |

2h05min |

Note: The Estimate was one item on the agenda of the Select Committee on this day – main business was the Garda bill. The time spent column represents time spent on the Votes. The group includes the Department, the Prison and Courts Services and the Garda. |

|

Environment and Local Government |

Vote 25 |

€3.4bn |

1 June 2005 |

1 |

2h55min |

The third biggest spending Department |

|

Agriculture and Food |

Vote 31 |

€1.4bn |

24 May 2005 |

1 |

2h35min |

||

Enterprise and Small Business |

€1.2bn |

18 May 2005 |

1 |

1h45min |

|||

Communications, the Marine and Natural Resources |

Vote 30 |

€507 |

7 June 2005 |

1 |

A Submission to the Committee of Public Accounts

by

Pat Rabbitte TD

September, 2005

VOLUME 2 - APPENDICES

Note

This companion volume to the submission reproduces a number of the papers consulted in researching the submission. A range of papers, reports and web sites for many countries were consulted and the materials studied are not all reproduced here. The materials reproduced are intended to provide a flavour of what is available on the subject from multilateral institutions, professional bodies, parliamentary bodies, finance ministries and the like.

Ensuring Accountability in Public Expenditure

Report of a Commonwealth Parliamentary Association Workshop,

Downloaded from the website of the Scottish Parliament: www.scottish.parliament.uk/msp/cpa/docs/EnsureAccleaflet.pdf

It has been argued that the principle behind legislative oversight of executive activity is to ensure that public policy is administered in accordance with the legislative intent. According to this principle, the legislative function does not cease with the passage of a Bill. It is, therefore, only by monitoring the implementation process that Members of the Legislature uncover any defects and act to correct misinterpretation or maladministration. In this sense the concept of oversight exists as an essential corollary to the law-making process.

Legislative oversight of the executive has been a contentious matter since the earliest days of the United Kingdom House of Commons in the late 14th century. In the case of the oversight of finance and the budgetary process, the crucial question is: In which organ of the state should the oversight role be vested?

Taking into consideration the well documented development of the U.K. Parliament, the one aspect of governing that tilted the balance of power with respect to the question posed above was the financial needs of the Sovereign. As the Head of State’s financial needs increased, so was the need to raise levels of taxation which eventually led to Parliament demanding the right to oversee the activities on which the taxpayer’s money was spent.

The importance of legislative oversight as a tool in monitoring government activities was underscored when Woodrow Wilson, later President of the United States of America, wrote in 1885:

“There is some scandal and discomfort, but infinite advantage, in having every affair of administration subjected to the test of constant examination on the part of the assembly which represents the nation. Quite as important as legislation is the vigilance of administration.”

While the principle of legislative oversight largely remains as it was espoused by the 14th century House of Commons and reinforced by the Wilsonian political philosophy, its application in modern days demands that there must be a set of objectives or standards against which it can be assessed and measured. If this is not done, then Parliament’s oversight role is unclear because there are no identifiable criteria by which to judge the reporting bodies —given the new politicoeconomic order where many governmental functions are being hived off to agencies outside ministerial control.

In this regard, the future of parliamentary oversight must be guaranteed by the functions that national constitutions assign to each organ of government to perform, with Parliaments ensuring then that the provisions governing Appropriation Bills are properly enforced and that preventive policies are put in place to mitigate against fraud, waste and abuse of public funds.

This report is intended to highlight some of the pertinent issues discussed and recommendations made by Parliamentarians,Auditors-General and representatives of international organizations and civil society at a three-day Workshop on Parliamentary Oversight of Finance and the Budgetary Process, organized by the CPA and the World Bank Institute.

The Workshop traced the origin of the concept of oversight by the Legislature as arising from the remarkable transformation of the U.K. Parliament from being a mere consultative forum, summoned for business and under procedures regulated by the Sovereign, to a level where it could ask the Crown to account for the monies collected from the people in the form of taxes. It was noted that this arose from the financial needs of the monarch. As the stature and authority of Parliament grew, it devised processes by which to transact the business before it as a way of ensuring effective oversight. The processes devised have over the years undergone modification aimed at equipping Parliaments sufficiently to exercise effective oversight of the executive. The modifications have produced processes varying in degrees of application and effectiveness. Yet those processes remain a means by which legislative oversight can be attained and ensured.

It was noted therefore that no taxes can be passed without the enacting of tax laws and Appropriation Bills by Parliaments. The passing of such Bills is also dependent on the Legislature having satisfied itself of the appropriate use of funds through the Auditor-General’s Report to the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) of the House. That is, the use of public funds must be explained and those who hold power are accountable to Parliament, the people’s representatives, for the use of those funds.

The concept of oversight, notwithstanding the problems in its implementation, was considered by the Workshop to be an essential function of the Legislature. However, to ensure maximum compliance to legislative authorization of changes in the levels of public taxation, constitution of the consolidated fund, sanction of allocations and withdrawals from the fund to meet demands for public services and purposes and to ensure adherence to authority in expenditure, the Workshop recognized the need to use extraparliamentary bodies such as the media in highlighting non-compliance as might be shown in the Auditor- General’s reports.

It was acknowledged that the framework for effective parliamentary scrutiny must take into account two important issues: first, the establishment of specific oversight mechanisms to effectively hold the executive to account for their activities, and secondly the need for a bipartisan approach in Parliament when overseeing executive activities. It was felt that this would raise the capacity of the Legislature to fulfil its oversight function.

There was consensus that the oversight mechanisms chosen must seek to address the interplay of the inalienable right of the governing party to be able and be seen to govern. At the same time the Members of opposition parties must be able to ventilate issues, criticize and put across alternative positions and policies within the modus operandi of the set mechanisms.

In addition, the Workshop recognized the problems faced in making oversight mechanisms fully operational, such as the perennial rivalry pitting the Legislature against the executive organ of the state in jostling for the imprimatur as the representative or voice and custodian of the public good. The Workshop explored ways to overcome obstacles in the quest for a truly participatory Parliament, especially for Members of the opposition parties in the House, which in effect aimed at having a minimum commonly accepted standard for specific oversight mechanisms that would pass the public’s approbation test.

There was overwhelming support for the view that much of the public criticism of Parliament’s weaknesses in the oversight of the executive could be ameliorated by oversight mechanisms such as the Public Accounts Committee, Budget Committees and the scrutiny of the whole House of Budget Acts. The repeal of hitherto constitutional constraints forbidding Parliaments from either increasing or reducing allocations contained in a budget before Parliament was also recommended.

On the subject of the budgetary cycle and the budgetary process and their implications for oversight, a constant point of reference was the recognition that budgets detail government’s policy priorities within the context of fiscal pressures and economic forecasts. It was also noted that in the Commonwealth, budget scrutiny underscores the rivalry between the executive and the Legislature in providing the public with:

Since budgets are accompanied by different or standard statements that highlight the executive policy focus, the Workshop felt that there was a need to improve the capacity of Parliament, its committees and public auditors to carry out their respective functions by providing them with sufficient resources, training and access to expertise that they may require in the budgetary cycle and budgetary process.

Participants agreed with the Kenyan Vice-President, HE. Prof. George Saitoti, MP, who, when officially opening the Workshop, stressed the importance of capacity building as Parliaments are the only institutions that are constitutionally mandated to debate budgets taking into account the interests of all national groups and strata in a country.

Budgets taking into account the interests of national groups were underscored in the discussions on genderresponsive budget initiatives from New South Wales and Queensland. Gender budget statements in New South Wales and Queensland rose from the realization that there was severe under-representation of women in decision-making positions and consequently in the budgetary process, which culminated in the allocation of fewer resources for women. In Jamaica, it was noted that the government had taken steps to improve its delivery of development programmes by the implementation of a financial management improvement project under programme budgeting. An important component of these kind of budgets is that they provide advance information as to expected revenue and expenditure policies, which is meant to assist in forward planning by the government, business groups and the community.

The Workshop considered such budget statements as useful in highlighting how a budget can affect the economic and social opportunities of a particular group in society such as women. Although they are not impartial documents, they were considered necessary for any government wishing to take a county forward by addressing the concerns and needs of any specific interest group.

It was felt that to ensure effectiveness of innovations in the budgetary cycle and the budgetary process, obstacles which impeded the Legislature in fulfilling its oversight role ought to be removed. Such barriers and limitations were stated as being commonly found in:

Finance Committees — The partisan attitudes of some government Members of these committees can hinder impartial scrutiny. Members of the committee invariably approve each line of the item proposed by the executive in the draft budget, while debate in committee is often limited as government Members are unwilling to discuss issues and are short on points of clarification.

Performance Budgeting — Currently, performance budgeting does not involve the submission of specific and measurable performance indicators, subject to quarterly and half-yearly reviews, which are presented by the Minister for Finance.

Parliamentary Review of the Budget — Members are not given long enough periods to review the estimates of expenditure as the budget unfolds.

Audit Reports — While constitutions often give the Auditors-General powers to review expenditure in all government ministries and organizations receiving public funds, resources to allow for the review of government expenditure in many areas are not made available to Auditors-General. Some organizations such as public or parastatal bodies continue receiving government funding long after their economic life span has expired. In the end they become mere conduits of corruption to bypass established procedures laid down by government.

The Workshop noted that the Jamaican government had agreed to establish an Appropriation Committee whose work was to examine issues related to the budget. Consequently, two new laws were passed aimed at tightening public utilities. These are the Public Bodies Act, which makes all agencies subject to the Ministry of Finance guidelines, and the Anti-Corruption Act, which widens the number of civil servants required to declare their assets and be subject to monitoring by the Anti-Corruption Commission.

There was consensus that the preparation of budgets should entail advance consultation with Parliamentarians who represent the people for whom budgetary plans and expenses incurred by the government after the passing of the Appropriation Bills are made and spent, respectively.

The accountability for funds is headed usually by a constitutionally created office of the Auditor-General. From the outset, the Workshop acknowledged that usually the relationship between the Auditor-General and Parliament emanates from the constitution. It was agreed that the relationship between the two should be balanced so that their roles and independence remain clearly defined and separate. In pursuance of their independent roles, it was agreed that the role of the Auditor-General is to assist Parliament to ensure that there is proper use of public resources by auditing government and those quasi-government institutions that receive public funding.The provision of fair and impartial audit reports and information to Parliament through the Public Accounts Committee and the presence of the Auditor-General during its deliberations on the audited accounts of the government and any other bodies receiving public funding are important measures necessary to assure the taxpayer that there exists a body to investigate accountability on behalf of Parliament. In turn, a close working relationship between the Auditor-General and Parliament enhances public confidence that resources are used with due regard to the efficient and effective running of the government.

The Workshop held the view that, in order to sustain this confidence and uphold the highest audit standards possible, there must be sound constitutional arrangements based on the principles of accountability, good governance and independent public auditing. The requirements for proper accountability should be based on:

Although audit offices provide assurance to Parliament and the public through their audit reports, the execution and implementation of any recommendations from Parliament is a common problem. Matters which should have been long dealt with often reappear in future audit reports. To maintain the competence of audits and the reputation of the Audit Office, the Workshop was of the view that audit offices should be separated from the general civil service through enabling legislation passed by Parliament. Such legislation or a specific Auditor-General’s Act should provide the audit office with a range of powers to obtain information so it can properly discharge its duties. It was further seen as proper that audit offices themselves must be subject to auditing by the highest professional audit body available in order to be accountable for their use of public funds.

In reaffirming the point that the audit office should specially be created and the Auditor-General appointed by an Act of Parliament, the Workshop also considered the value and necessity of an independent audit office as being a building block to ensure trust and confidence among the concerned parties. For this reason, there must be a constant flow of information between the Auditor-General and Parliament in order to emphasize the two entities’ functions as complimentary and not competitive. The Workshop, therefore, concluded that these offices must be independent and not part of the Public Service; and nothing should be done to dilute their authority. Their tenure of office must be made secure through appropriate parliamentary legislation.

In the Commonwealth, committees are used to refer to the formation or constitution of a group of Members of Parliament who are specially named to address a specified mandate whose terms of reference and remit are spelt out.

A committee is expected to operate according to the procedure of a particular Parliament; such a committee is distinct from the Committee of the Whole House and any extra-parliamentary bodies including party caucuses or inter and intra party formations. It was noted that successive Parliaments have found committees a flexible means of accomplishing a wide variety of different purposes.

Committees may be given different powers to meet different circumstances. They may be created ad hoc to meet a particular requirement or be reappointed from session to session or from Parliament to Parliament to carry out a more continuous function.